‘India is the only country that is not overwhelmed by one of the three monotheistic religions. Hinduism has remained the most popular faith of the land since time immemorial,’ says Jan Ross

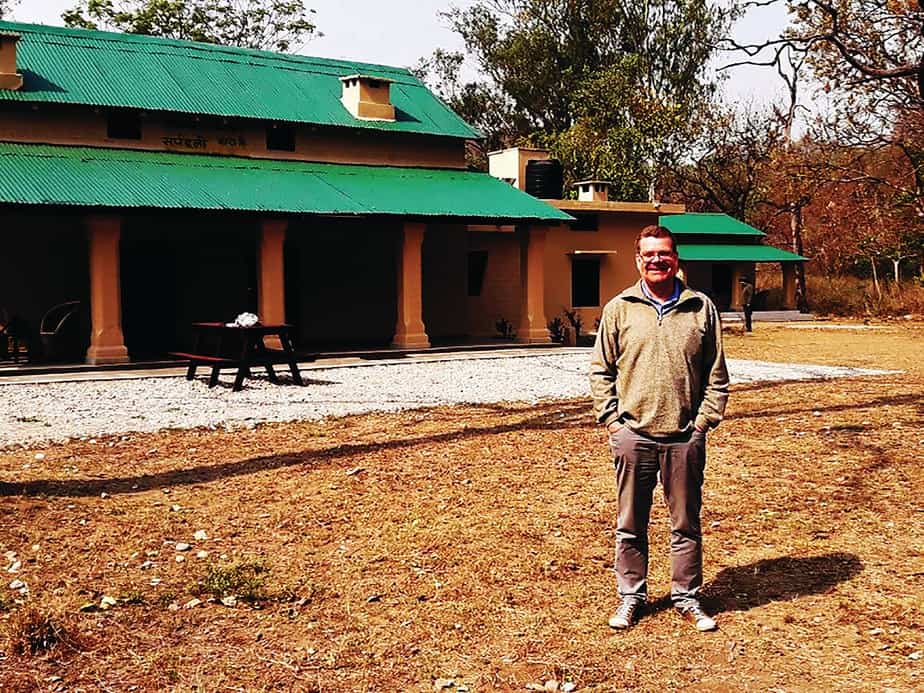

Jan Ross, 50, was the foreign affairs editor at Die Zeit — the leading German weekly long-form newspaper — for 10 years before he opted for the job of a reporter in Delhi. Perhaps he wanted to get out of the sanitised environment of a newsroom in Hamburg, and go out in the field to report from the part of the world that fascinated him from the very first time he visited in his early teens for three days in the late 1970s. That’s India.

He shifted to Delhi nearly five years ago with his wife Ina Ross who’s a visiting faculty in the National School of Drama. His two sons, Leo and Benneddikt, and parents, have come and spend time here. It has been an enriching experience for the whole family. And the long-held biases about India — the so-called land of snake charmers and wild animals — has given way to a more informed view.

In the last few years, Ross has been travelling the length and breadth of this country of continental proportions and prolifically reporting about various aspects of this diverse country. Unlike the popular practice amongst the senior foreign correspondents, he doesn’t hire an Indian assistant to furnish information for him. He likes to go to ground zero in person.

In the past many years of his Delhi stay, he has written dozens of stories about various aspects of this diverse country where anything can happen at any time. He’s even written for children and did a detailed piece on India’s fascination with cricket. His reporting will go a long way in creating an image of Delhi that’s beyond the rape capital of the world.

That’s on the professional front. But Ross’ relationship with India is far deeper, is more of an intellectual engagement that has been enriched by a sort of faceoff between the Eastern and Western philosophies, religions and the way of life. A trained classicist, he’s well versed with the ancient Roman and Greek texts. He’s knowns Latin, apart from host of other languages. These ‘Pagan’ or pre-Christian religions or other nature-based spiritual paths were dismissed from whole of the continental Europe with the advent of Christianity, and in the Middle-East with the spread of Islam. Ross is fascinated by the fact that “It’s only in India that Hinduism — the original religion — has not survived, but has flourished.”

Hinduism is considered an Eastern extension of Paganism or Hindus may come to accept Paganism as European Hinduism, depending on which side of the debate you belong, as the two have common roots in shamanism, nature worship etc.

A Catholic, Ross is fascinated that Hinduism flourished not because the peninsula remained isolated but Hinduism somehow was able to assimilate various influences for over two millennia without losing its inherent character. Though India has one of the largest Muslim populations in the world, only second to Indonesia, the community is still considered a minority in popular perception.

That Hinduism —the only Pagan-like religion — flourished is a matter of prime interest to Ross. He has been to Kashmir a few times with his wife Ina. In Srinagar, when he visited the famous Martang Sun Temple, Ross was amazed to find the temple structure similar to, almost a replica of, Greek style temples. “Globalisation is not just a 20th century phenomenon,” concludes Ross, adding, “the influence is absolutely obvious. This temple could have been in any of these places like Sicily or Turkey.”

The spread of Christianity was fairly aggressive and Pagan mythological figures were either seen as demons or manifestations of evil. For centuries, Christianity has had a profound impact on the polity. Paganism was considered dangerous, primitive and obsolete; therefore it needed to be rooted out. It’s no surprise, then, that Paganism is extinct in countries like France, Germany and the UK.

“Since the Renaissance, there has always been an undercurrent of discontent when it comes to Christianity,” points out Ross. And Paganism has remained the point of reference amongst people who wanted to challenge Christianity, and, in the process, initiated important intellectual debate. Drawing the distinction, Ross points out that Paganism, is something difficult for a Christian to adopt as ‘believing’ is more important than ‘doing’. Paganism’s religions core references are mythological and rituals are important, not the context.

How come Christianity — or for that matter Islam — failed to overwhelm the subcontinent? Why did Hinduism flourish in India while the whole world embraced one of the three prime monotheistic religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam? Ross says he’s not qualified to make that assessment, but says without an iota of doubt that India has an incredible capacity to coexist in diversity. “People can coexist peacefully, parallelly — it’s not a bad thing,” stresses Ross.

He gives the example of his visit to the Aligarh Muslim University where a Sufi shrine is frequented by both Hindus and Muslims. And that isn’t even the only shrine that inspires faith amongst the two biggest communities in India: Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi, Salim Chisti Dargah in Fatehpur Sikari and Moinuddin Chishti Dargah in Ajmer attract both Hindus and Muslims in large numbers.

Religion in India, unlike in the other parts of the world, is just one of the many predominant identities that define people. There is also caste, region, linguistic and feudal setups that “destroy this pure religious contruct,” Ross says.

Indian secularism is different from that of France, which is all about “anti-religion”. India’s secularism is far more inclusive, of the “live and let live” kind. And one of the most fascinating things about the country that Ross discovered is to “be relaxed” about differences. This explains why plurality of the land and its culture has remained intact for centuries.

Drawing from his experiences in Europe, Ross says, “Homogeneity creates pressure to conform.” That to a great extent explains why Europe is struggling to cope with the influx of immigrants.

Ross has not remained unaffected. His stay in India has made him understand that the impact of colonialism. Also, how that has shaped foreign policies of countries that have emerged breaking the yoke of colonialism. “Now I can understand better the reason for not trusting the West,” he concludes.

Ross has internalised India like very few foreign correspondents ever will. India to him, remains a repository of intense experiences of various flavours—colourfulness at time, oppressive at others, also exhilarating.

Ross has read the best of Indian literature and contemporary non-fiction work and is more Indian than many of the native public intellectuals.

It’s not difficult to forget that he’s a German, for he can discuss with an ease of a wide range of issues from Mamata Banerjee’s Bengal to what Mark Twain wrote in his essay about Mahatma Gandhi. While doing so, like a good witness, he isn’t judgemental.

Jan and Ina made Delhi their home for years. They feel a sense of nostalgia even before they are to leave towards the latter half of the year.