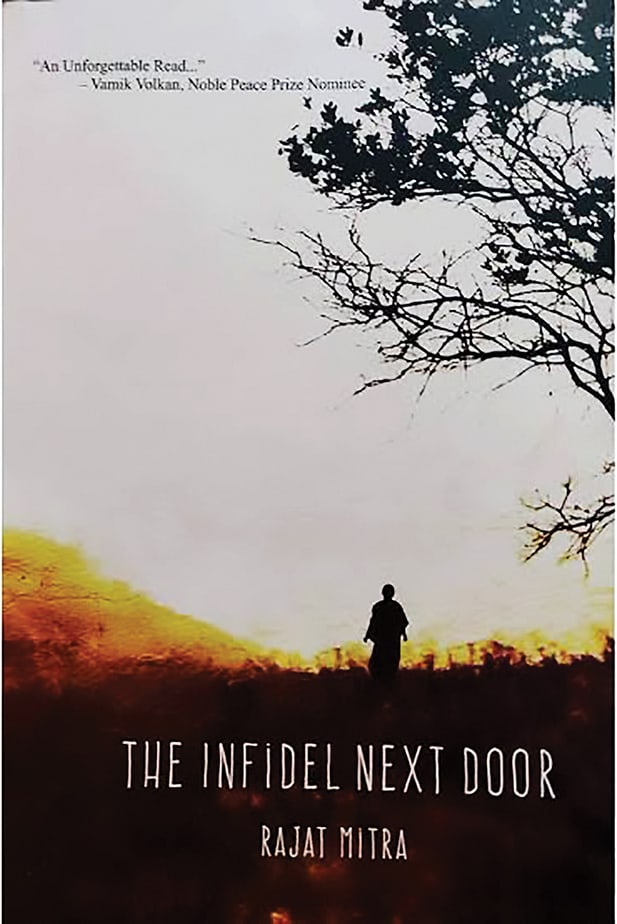

Psychologist Rajat Mitra’s radical book about transgenerational trauma, based on the lives of Kashmir Pandits, attracted the wrath of both Left and Right

Psychologist Rajat Mitra, who has worked in India and abroad, was specially deputed by the then chairman of National Human Rights Commission and former chief justice of India, J S Verma, to support victims in the Muslim refugee camps post 2002 Gujarat riots. His recent book The Infidel Next Door however deals with his experiences with Kashmiri Pandits who were thrown out of the Valley, lodged in various camps in Jammu for decades.

He was helped by his wife Nidhi who’s also a psychologist par excellence. It’s a fictional narrative shaped by interview of the victims and many Muslims in the Valley on the overarching theme of transgenerational trauma.

Transgenerational trauma, explains Mitra, is passed from a generation of survivors to the second and further generations via some sort of post-traumatic stress disorder. He gives the example of families of the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps. They don’t stock up their fridges, a reflection of the fact that inmates were not allowed to store food in the Nazi camps; a Jew found with a loaf of bread would be summarily executed.

“No one told them not to stock up their fridges. It just became a family practice that subsequent generations adopted without questioning,” Mitra explains. It’s true for Kashmiri Pandits as well. He’s of the view that it’s important to recognise the injustices of the past, sit across the table, discuss and deal with it — not ignore as if it never happened — before it erupts into something ugly.

He gives the example of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of South Africa constituted in 1995. In a court-like setup, evidence was gathered and both the victims and the perpetrators were encouraged to speak up. Unlike the Nuremberg trials to prosecute Nazi war criminals after World War II, TRC was meant not to persecute but heal the country by being upfront about human rights abuses during the apartheid regime. TRC was seen as an essential step towards ensuring a transition towards full and free democracy in South Africa, where both the white and the black population can partner equally in the nation-building.

Mitra in his radical book shows that reconciliation is important for lasting peace and can only be achieved by dealing with the truth head-on. But neither the RSS nor the Left intelligentsia, in India or abroad, is happy with this book, which Mitra maintains is an “academic pursuit.” He’s neither a right-winger nor a left-winger, but a rational individual with scientific temper, such people are usually left of centre.

RSS is not happy, which he has been communicated in tacit ways, for Muslims in this book are portrayed as compassionate people who regret what happened to Kashmir Pandits, some even like Hindu religious practices — puja–and have shown transformation in their long-held views. The Left intelligentsia is not happy, for they smell a conspiracy and judge him for choosing to do a book on Kashmiri Pandits languishing in various camps, and not their Muslim brethren.

Mitra was greeted with hostility and protests when he travelled to the US recently on a three-month lecture tour that was supported by the Kashmir Overseas Association and the State Department of the US. At Ohio University, the situation got so bad that he was offered security cover. His lecture was interrupted and he was castigated for spreading lies, and for being driven by some ulterior motive and agenda.

While explaining ‘transgenerational trauma’ in one of his lectures, he gave the example that Kashmiri Pandit lodged in the camps for now nearly three decades have stopped telling their children bedtime stories. He was interrupted and asked to stop his “bullshit, utter nonsense” and was advised to rather look at the plight of Kashmiri Muslims. To which Mitra tried to stress that suffering has no religion, nor has a degree, and you don’t compare the sufferings of two communities. “This is an analysis from a psychological point of view,” he added.

“I’m sorry to say,” Mitra elucidates, “the atmosphere in US campuses is highly polarised.” And the abrogation of Article 370 has given the necessary impetus to the Khalistani groups — encouraged by the ISI — Kashmiri Muslims and Pakistani youth to regroup together. The situation is fairly “tense”. They talk of India being overwhelmed by the politics of majoritarianism. But Pandits were always a minority in Kashmir. The hypocrisy of ideological leanings prevent an open debate – this is what Mitra regrets. The impulsive need to attribute motives to a contrarian view, call names, stifle voices, is not liberalism.

Students were not the only one who interrupted him, so did Aatish Taseer—Government of India recently revoked his Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) card in retaliation to his Time article that described Narendra Modi as ‘Divider in Chief’. While he interviewed Mitra for an hour on behalf of Al Jazeera in the US (not telecast yet), Mitra was told in plain words, “No one will accept his thesis.”

Mitra is not bothered, a new idea takes a while to be accepted. Silence is one of the potent vehicles of transgenerational trauma. The ills of the past — whether colonialism, racism, slavery or genocide — cast a shadow on the future of the families of the victim. It’s a psychological fact, by way of “epigenetic inheritance (markers from parent-child that affects the traits of offspring without alteration of the primary structure of DNA)” explains Mitra. We should be able to deal with this fact. Don’t shoot the messenger if the message doesn’t suit your preconceived notions.

Mitra’s forthrightness on his position, based on psychological studies or factual premise, has led him to court controversies in the past as well. A few years ago, he questioned in an article: Why there are no medieval temples in Delhi? There are old mosques, churches and even gurudwaras but no temple which is older than a hundred years. The oldest existing temple in Delhi was actually built in 1939 — the Birla Temple — by G D Birla and none other than Mahatma Gandhi inaugurated it, Mitra informs. But no one will talk about this, for silence is seen as a solution.

Silence doesn’t heal the wounds of the past, it only perpetuates it. It’s like a “family secret” that everyone knows about but never speak about it. He gives the examples of sexual assaults, even rape of family members of the Sikh community during the Partition post-independence. A part of the family of the Sikh community who migrated to India stayed back in Pakistan and some even converted to Islam. No one talks about them — not because they are forgotten.

Mitra feels Ram Janmabhoomi Case is a good opportunity for reconciliation. But only if the polity and literati can get over the polarity of the communal and ideological polity.