No jubilation here: R-Day has little meaning in the lives of the working class, even 69 years after we got sovereignity

While the middle class rues that Republic Day falls on Saturday this time, which is anyway an off day for most, in the informal sector, not many people can enjoy a holiday. The working class that has no job security — daily wage earners, unskilled labourers — is deprived of a day’s income without really knowing why, as the concept of a republic is not clear even to those who are educated.

Patriot asked “We the people” who are now sovereign, as to what this day means to them personally. As live images of the parade are streamed into each and every home, the poor don’t even tune in, as they get little respite from their existential quest. This year, many of the middle-class families who are hooked onto Netflix or one of the social networking sites, won’t even watch the parade on their televisions.

Meet Namita, a middle-aged woman who works as a part-time cook in various households in CR Park. Her two children are married and settled in Kolkata. She left her husband for good because of his drinking problem. At the age of 50, she has found new freedom, emanates self-pride that’s difficult to miss, is fairly well informed about life in general.

But when posed with a question about Republic Day, she confuses it with Independence Day. “If we got independence on 15 August why do we celebrate January 26?” she seems fairly puzzled. She isn’t aware of a sacrosanct document called the Constitution or samvidhan that’s the basis of democratic government of the people, by the people, for the people.

She laughs, and then pauses for a while to ponder over her interface with the government. “It’s difficult to get things done unless you pay bribes. My life has improved, but not because of the government, due to my own labour. I live in an unauthorised slum, I can be thrown out any day. I have a power connection, I pay electricity bill even if I don’t have enough to eat. Things have improved, I have more sarees to wear than I had 10 years ago. But in my life, the state, primarily represented by police and municipal workers, behave like greedy thieves. There’s no respect for us. Netas come every few years, but I don’t even remember their faces. I don’t even get a holiday on Republic Day.”

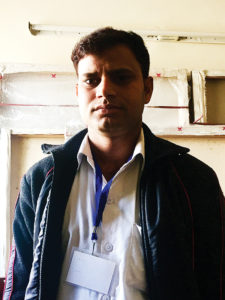

Yogeshwar Pratap Singh, 27 years of age, from Mathura, is an electrician working in Noida. He had to discontinue study after school, for his family was too poor to provide for him. He started working in his late teens, and travelled places to find a secure job. He hasn’t found one till date, but is hopeful. “Independent India is good for the janta (people at large), they say. I agree. Things have improved in my lifetime, when I was a child in my village many didn’t have enough to eat, even wear. Now they even have a motorcycle, mobile phone,” he says.

He’s tongue-tied when asked what Republic Day means to him. Finally, he utters few words tentatively, apprehensive that it might sound politically incorrect. “Frankly, to me this day has little significance. It’s just another day when people don’t go to work. My clients are at home, they call me to fix their electrical appliances. So, for me it’s a busy day.”

As an afterthought he adds, “My country has given me freedom, but that’s it. What do I do with that freedom? For they didn’t help me find a job, help me get an education. He claims he knows more about electricity than an engineer, but has no degree. I have no house. I’m frustrated. When I see a successful young man from an affluent family, I’m reminded of my pathetic state.”

But he is certainly better off than Kalima, a skinny woman entering middle age, who has four children. Her husband is unwell and therefore unemployed. The eldest is 17 years old and works in a barber shop. She works in seven households as part time domestic help in a Noida’s upmarket colony. She works 12 hours a day, seven days a week. She is an excellent cook, but six of the Hindu families she works for won’t allow her to inside the kitchen, because of her faith. “They are all non-vegetarian, but still are not comfortable letting me cook for them. They feel Muslims are impure,” she says, without betraying any emotion.

Ask her about Republic Day and she’ll give you a blank look. After a bit of explanation, she quips, “Oh that’s why they are selling flags.” Ask her about the tricolour, all she is able to say: “It shows we’re Hindustani.”

The significance of Republic Day in her life is that she doesn’t even know it exists. Seven of her family members, including her long ailing mother-in-law, live in a one-room shanty. Her life and her house have no space for anything that’s celebratory in nature.

“I’m proud to be Hindustani, at least we have a roof over our head,” she asserts. Perhaps she does know, after all, what the fuss is all about.

Very few watch the Pomp and show nowadays

Seventy years ago, India became a republic and a welfare state and Republic Day parade in the capital, an event hosted by the Ministry of Defence, is perhaps the biggest annual event by the government.

The three-day celebration ends in the magnificent Beating the Retreat ceremony. It’s celebration of our statehood, of the liberal ideals and values enshrined in the Constitution.

The chief guest at the R-Day parade, a head of state or government, is indicative of evolving foreign policy. A head of state of a smaller country is bound to get overwhelmed by the display of military might at Rajpath, while that of a big and mighty country, it’s an occasion to come to terms with India’s emergence as a regional power in the comity of nations.