When children from India adopted in Europe in the past come looking for their biological parents, they do find the truth – but it is not pretty

Many of the children adopted from India by couples in Europe and the US in the 1970-80s have grown up looking very different from their white parents, in white neighbourhoods. All their friends and schoolmates look different, making them conspicuous and reminding them time and again that they don’t belong to this place.

These circumstances created a craving to connect to their roots, leading some of them to come to India in search of their biological parents. They want to ascertain why they were abandoned, the primary reason being that they were born out of wedlock. Many of them made this difficult journey, sometimes repeatedly for many years, against all odds, to connect with their roots. Very few met with reasonable success, like Arun Dohle and Anand Kaper, German and Dutch by nationality. That too because they made it the mission of their lives to help people like them to connect with their roots, not just in India but across the globe.

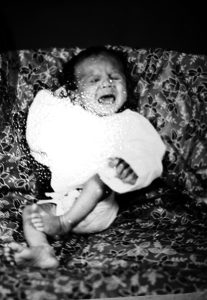

Anand Kaper

Anand Kaper is 43 years old, and has been teaching children below 10 years for almost half of his life. He was adopted from Mumbai by a Dutch couple living in Apeldoorn in the Netherlands where he has lived ever since. His younger sister was also adopted from India so is his wife, Sini, nearly the same age. They have two wonderful children: Aishwarya is 9 and Roshan has just turned 7. He only speaks Dutch and English.

Anand had many friends in school who were fairly accommodative towards the only brown child in the school. He has had a wonderful relationship with his parents and lives in the same city as them, apart from a phase where it was difficult to communicate with them.

From the very beginning, he and his sister were told that they are adopted as there was no way it could remain hidden. Initially, he didn’t like the colour of his skin and wanted to be a white kid like others. After a certain age, “I liked my brown colour,” he says. It’s not a coincidence that many of his friends are adopted children who grew up in the West and he ended up marrying one like him. “That has to do with recognition of common issues. They identify with the psychological aspect of how it feels to be abandoned,” he says. It’s become an existential question: Why were we abandoned and as Kaper puts it, “cut off from Indian culture, family, happiness.”

He pauses to express this feeling of being unanchored in the words: “I feel lost in this world like I don’t fully belong to a place.” Having said that, he feels more at ease here in the Netherlands for he’s not “familiar with the unwritten codes and rules in Indian society.” Language is a barrier, though he enjoys the Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) status. And has been visiting India for many years every year to try to connect to his roots.

It was a big challenge. He started his search at the Dutch adoption agency but very little information was available. All he wanted to know was why he was abandoned in an orphanage in Mumbai when he was barely six days old. He came to Mumbai, but all his efforts to find the name of his parents bore no fruit. The surrender document is private and confidential; it cannot be shared with anyone — it’s done to protect the biological mother. He even met Maneka Gandhi, then Minister for Women and Child Development, but she was of little help. He had no idea where to go next.

In 2017, he adopted the DNA fingerprinting route. By some divine providence, he found the match with a second cousin of his who’s settled in the US, he refuses to share the family name as yet. He explained his predicament to this distant cousin who agreed to share the family tree with him — one of the persons on the tree is his father.

After much effort, he persuaded one of the uncles from the family tree, based in Mumbai, to get a DNA test done. To compare DNA profiles takes two months, and the results arrived last month, changing Kaper’s life forever. Tests proved that their DNA overwhelmingly matched to the extent this uncle, 10 years older than him, is actually his paternal half-brother. Put simply, the two have the same father. Kaper’s biological father, who died a few years ago, was having an extramarital relationship with his biological mother. This information came as a rude shock to his newfound halfbrother.

Kaper has helped many adopted people in similar quests get the satisfaction of connecting to his bloodline.

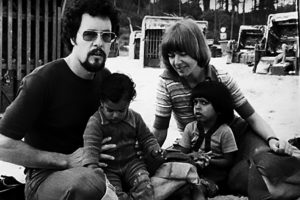

ARUN DOHLE

In 1973, German couple Michael and Gertrude Dohle adopted Arun from Kusumbai Motichand Mahila Seva Gram in Pune. Like Kaper, he grew up with an adopted sister, “brown children of white parents,” he says. He experienced a tension between the two identities and made up his mind to look for his roots.

It took 17 years, including seven years of intense litigation, The matter went to the Supreme Court to force the authorities to show him his adoption papers that would reveal the identity of his mother. Dohle met his mother in 2010. It was a somber, composed yet emotional meeting. Dohle says his adoptive parents were friends of NCP leader Sharad Pawar’s brother Pratap, the one who’d facilitated the adoption.

Unlike many others, Dohle had an advantage, his adoption was well documented. Dohle helped others in similar quests. He found that the adoption is no act of benevolence but human trafficking, a “forced migration” and a “form of contemporary slavery.” Given the money involved, market forces of demand and supply are at play and some 1,000 children are exported every year from India. His own adoption was shown to German authorities as a case of an abandoned child to circumvent the need to seek permission from his biological mother. He calls the whole process as “erasing my original identity.”

Dohle is not against adoption but “the trade in children in the name of adoption.” With a like-minded EU bureaucrat Roelie Post, he founded an NGO called Against Child Trafficking (ACT) and unearthed adoption scandal after scandal in India, Ethiopia, Sri Lanka, Columbia, Thailand— to name a few that involved abduction of children, false documentation and cash trails. Last year, Post was fired from the EU.

Dohle clarifies that adoption has little to with child protection, which is the responsibility of the State, and for that, the government should support the poor as poverty — and rarely a child born out of wedlock — is the single largest cause of parents deserting children. He has been fighting this protracted battle without any institutional or financial support. There has been some success, recently the Dutch Council for Criminal Justice and the Protection of Juveniles, on its own initiative, has advised phasing out intercountry adoption with immediate effect.

But it has taken a heavy toll. Dohle who spends a lot of time in Pune says his situation in life is quite “dramatic” as “I have given up my flat (in Germany), social security system. I worked hard with no compensation, struggled to change the adoption laws in EU, and I’m not in touch with my adopted family.” Hopefully, there’s the light at the end of the tunnel he’s in.