The overwhelming sentiment in the riot-hit areas is a feeling of being wronged by the state. Yet communal harmony survives, holding out hope for the future

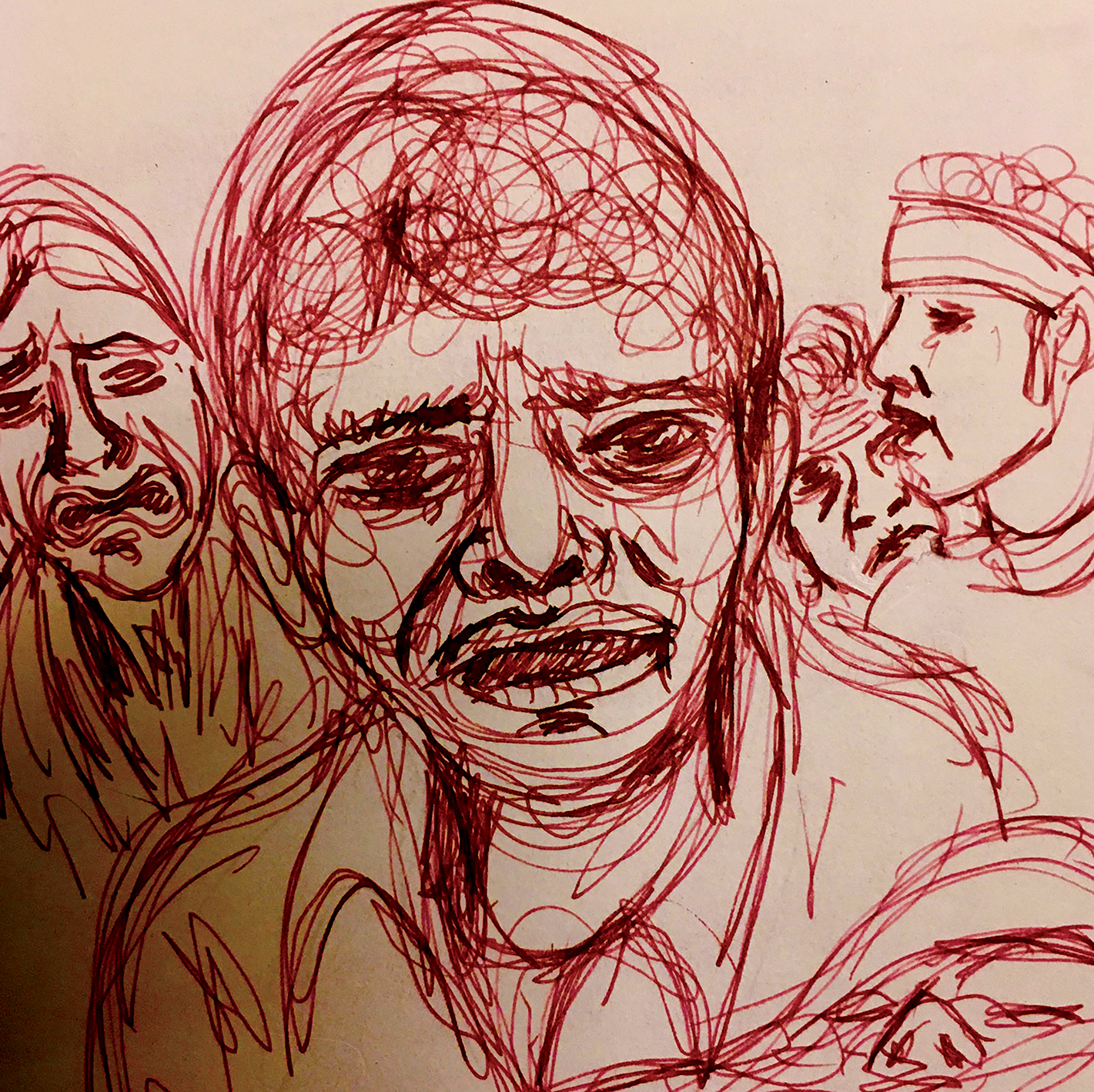

AS THE dead bodies of the victims of the communal clashes in North East Delhi arrived, the family members became inconsolable. Theirs is not a cry of grief but that of pain and agony.

The butchered bodies are the result of hatred fermented by, locals believe, outsiders. The two communities have lived together peacefully for years. Most of them are migrants and lead a challenging life, their time is predominantly consumed in providing and working towards a better future for their families here in Delhi as well back home.

They say that they know that this pogrom happened to make them fight with each other, ferment anger and animosity. The killings that went on for three days while the Delhi Police did little to stop it, was a message for the largest minority–Muslims–are painfully reconciling with the process of them being turned into second class citizens. They have to be content with what they get if they are to live in this new India. They don’t even have the liberty to protest.

The message is loud and clear. They have nowhere to go. Where will they go? This is their home, too.

Hindus and Muslims are both a bit perplexed that the miscreants were allowed to kill and loot for three days. “RSS was in police uniform,” locals allege, describing the perpetrators. They could have been stopped and a lot of what followed could have been averted. But the police didn’t do anything. “It was orchestrated,” declares Thakur Mangal Singh, the 70-year-old patriarch with a handlebar moustache seated outside his property — which includes a dozen

shops in a row in Shivpuri. “People were being killed and the police came, saw what was happening, and went back,” he adds.

Across the road, alongside the drain, gutted cars are collected in a pile. People come and click selfies there. Parihar owns two ‘Baraat ghar’ that were converted into parking lots a couple of years ago. There were some 100 cars parked here, all have been gutted down. All that remains are mangled metal frames lined in two files. It feels like this part of the city has suffered carpet bombing.

Parihar calls it the lane that separates Shivpuri, a Hindu ghetto, from the adjoining Muslim dominated areas as “border”. On either side of the border, Delhi Police remained a mute viewer as violence was unleashed. A trade merchant, who is a tenant of one of the shops owned by Parihar, a Hindu by faith, employs some sense of humour to give perspective to the tragic happenings, “You can accuse Delhi Police of anything other than that they are communal–they didn’t come to the rescue of Hindu and Muslims alike.”

Despite all that has happened, people are helping each other to deal with the trauma and in the process to rebuild their lives. On 28 February for the first time in a week, people came out in large numbers to buy essential commodities. Many funeral processions added to the crowd and stirred the dust that hung low in the air. People are tense and afraid; acutely worried about their future, as more bodies are discovered in the burnt wreckage and in the drains littered with filth.

Life has to go on, women are out with their children. The streets are dusty, stones and pebbles lay strewn around, gutted cars look like an art installation of doom. The people know things will never be the same again. Small children are fascinated by what they see, and older ones are scared out of their wits. They can’t sleep at night, wake up with a start, with a feeling that something bad is about to befall, that they are not safe in their homes.

For some everything is destroyed, the sole breadwinner is dead. Deceased Arif is from the extended family that manages the parking in Khan Market. He was missing for a day before the family learned about his brutal death. His remains having just arrived from the mortuary are being prepared for the burial. The women of the house gather in a windowless room. Mother, wife, and the daughter are stoic, sitting still with blank expressionless faces. Too much pain has a numbing effect. His three sisters cry holding each other in an embrace. “Is this aman shanti (peace and brotherhood)?” they yell. Their loud cries pierce the damp air locked in Gali No.4 of Jaffarabad.

They all feel wronged, Muslims in particular. Like a son who has been disowned by his mother. In the narrow streets, people walk listlessly. The burden of the past is hard to bear and the future looks grim. The past can’t be undone, but some try to help the grieving and the homeless who lost everything in the riots. The locals are helping people with food and clothing. In many cases, Hindu and Muslims saved each other’s lives.

Four-year-old Aaradhya, accompanied by her father Ritesh Jain, is on a bike distributing biscuits and oranges to rickshaw pullers with a smile on her face, a soothing sight. A Sikh family distributing food refused to talk, for this was God’s will and not their generosity.

Delhi Police and the media are equally hated in this part of the city. “They both are not trustworthy,” declares Ritesh Singh, a young man who sports a bushy mustache. He resides in Gali No.1, Khajuri Khas. He hugs his Muslim neighbour to declare, “We have lived here together ever since we were born and will continue to do so till we die.”