People who spit venom on social media have a huge following and many of them are even considered online stars

Last week a man, Shubham Mishra, was arrested by Vadodara police for threatening to rape standup comic Agrima Joshua. He had posted a video on social media which was supposed to be a “warning” against her alleged insulting of Chatrapati Shivaji in a stand-up show more than a year ago.

Mishra’s video was full of abusive language and lewd remarks directed towards the comedian that irked a lot of celebrities, especially stand-up comics. The arrest came a day after the National Commission for Women took cognisance of the whole matter and issued a notice.

In a similar case, Mumbai police arrested one Imtiaz Shaik, who also made a video threatening Joshua. Shaik, who on social media assumes the pseudonym Umesh Dada, has more than 3 lakh subscribers on YouTube. Videos posted on his channel are full of lewd, misogynist remarks directed at celebrities and journalists. He makes videos with “supposed” warnings — according to him these warnings are posted against people detrimental to national interest.

The fashion in which these videos are made is particularly of interest. This style of video making was copied from internet sensation Vikas Pathak (Hindustani Bhau).

Last year, a reality TV show Big Boss, notorious for inviting controversial figures from public life, invited this social media star Vikas Pathak as a contestant. Pathak is well known for his unique style of making videos — sitting in a car and abusing a person as a “supposed warning”. His ‘style’ has earned him a huge follower base.

Various social media content creators — to capitalise on his following — made him more famous by creating their own content featuring his style. Pathak became an overnight sensation and that gave acceptance to the kind of “content” and “style” he used. He now has more than three million followers on Instagram.

Vikas Pathak also faced backlash for his style. YouTube banned his channel for being abusive. But that has not affected his popularity. The two men — Umesh dada, Shubham Mishra — copied his style of making videos.

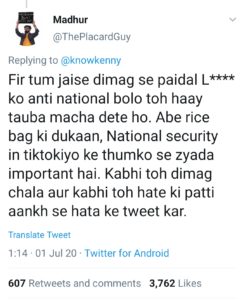

Before this incident got traction, on 1 July, Mumbai-based comedian Kenny Sebastian wrote on Twitter about the loss of content creators with the ban on Chinese app TikTok. A Twitter user Madhur (@theplacardguy) countered his argument, while doing this he used the term “rice bag converts” — a communalist slur used against Christians for following their faith for material benefit. This slur has often been used against Christian content creators for social media sites. The Twitter user has more than 60,000 followers.

Ironically, these people who abuse on social media have a big following and some of them even show allegiance to the power that be and consider their acts and words are justified by their popularity.

A few months ago a debate occupied social media — “YouTube vs TikTok”. The subtext of the debate was written by a roast video of a TikToker Amir Siddiqui by famous YouTuber Ajay Nagar Aka Carryminati with an assumed idea that “TikTokers are not talented”.

Some of the opening line of this video was: “Fark nahi padta tumahara swad khatta hai ya meetha, tum star ban sakte ho” (It doesn’t matter whether your taste is sour or sweet, you can become a star). The video received a lot of backlash but there were also those who supported Nagar.

Ajay Nagar is a sensation among his followers because of his roast videos. One of his ardent followers, a 16- year-old student, Rohan (name changed) says, “I watch his videos because ye meetha (homophobic slur used to refer gays) ki acche se leta hai (he doesn’t spare gays). Nagar has around 24 million followers and he has been making videos since he was a teenager. When his video on TikTokers was taken down for its umbrageous content, YouTubers like Ashish Chanchlani, Bhuvan Bam, Harsh Beniwal came out in his support.

Nagar enjoys a huge following base, which includes teenagers. When his video was taken down from YouTube for being objectionable — that follower base wrote a lot of hateful things against TikTokers on the internet to show their support for him.

Not only Ajay Nagar, YouTubers like Elvish Yadav, Lakshya Choudhary with following in millions often post content with objectionable language — misogynist, insensitive, homophobic remarks. They say that their content is “roast” — a form of humour where the subject of a joke is an individual guest on the show to amuse a wider audience.

Interestingly, many social media stars especially on YouTube derive their support base from their caste and they often come in conflict with other castes for that reason.

“Hate” a shortcut to stardom

On social media, hate is a well tested instrument to achieve stardom — the highly democratised way of functioning and absence of well defined policies on social media platforms — legitimising oneself through prejudices, hate toward a community, gender and even individuals has become a well-adopted strategy.

Recently retired Army General GD Bakshi abused a fellow panelist on national television. Instead of backlash, he received a lot of support on various social media platforms. The incident speaks volumes of how hate is now a well-established tool to gather supporters and achieve stardom on social media sites.

A man who used to call himself Grandmaster Shifuji Shaurya Bhardwaj on Facebook, Twitter and also circulated on WhatsApp Groups is still a famous name. In many of his earlier videos — before he was exposed, he portrayed himself to be a high ranking army officer. Ironically, he was even invited to panel discussions on TV as an Army officer in debates on crucial topics like surgical strikes.

Despite this, Bhardwaj is still followed by millions. He often abuses people branding them “anti-nationals”. Even when he was trying to pass himself off as an army man, the only saleable product he had was hate and that has not changed.

Kamal R Khan is another prominent name when it comes to hate-filled social media celebrities. He is an actor and producer, and now a film critic. He has been notorious for his comments — in bad taste but enjoys more than 5 million followers on Twitter and more than half a million subscribers on YouTube. After the death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput, many celebrities spoke against Khan for spewing hatred including Manoj Bajpai, Hansal Mehta, among others.

Khan derives his following from his bizarre opinions about Bollywood, he capitalises on audiences obsession with the industry — people wait to watch his videos, his review of Bollywood movies and actors.

Meme and trend culture

Becoming an overnight sensation through internet memes ( widely shared videos and images that are humorous in nature) is now a regular phenomenon. Meme culture seems harmless as it has a very short life span and is humorous. Memes like “Government Aunty” to “Nagarpalika Guy” make them stars.

Vikas Pathak too was made an internet sensation through these memes. Social media teams of various companies, individual content creators produced memes on him to capitalise overnight fame. Not only him but various other social media stars are the result of this culture. It looks like some of these internet stars who are spewing “hate” are Frankenstein’s monster.

The pressure on social media teams of various companies forces them to innovate. Streaming platforms like Netflix, Amazon try to stick to their own content and avoid employing trendy memes. But not do this on social media.

Being trendy even forces big social content creator companies to cross boundaries. Recently The Screen Patti, an online content creating company made a video on TikTokers that was in bad taste and many viewers called it homophobic.

Absence of regulation

On social media, if something is objectionable, anyone can report it to the platform but it is up to the social media site to act upon it –it takes its own time and discretion to remove or keep such a content. But there is no law that binds these social media platforms to act on the objectionable content.

The Observer Research Foundation in March 2018 released a study that was a statistical mapping of hate speech on social media pages. The study revealed that the most explicit basis of hate was “religious practices”. The study started in July 2016 and data gathered from various social media pages during a two-month time period spread over 12 months. Most of the comment inciting hate was directed towards Indian Muslims.

French Parliament has passed a law asking social media companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google to remove hateful content within 24 hours of its posting. Content pertaining to terrorism and child pornography must be removed “within one hour”. Failure to comply will cost these companies fines of up to $1.36 million. But in India any such law does not exist.

Time and again activists, lawyers have raised the issue of online hate but the debate fails to reach any fruitful conclusion due to fear of curbs on free speech by the government and concerns of privacy overshadows any debate over this topic.

In 2018, the Narendra Modi government announced that it was planning to amend Section 79 of the IT Act and made it mandatory to weed out “unlawful” content and trace the origin within 72 hours. But the plan was dropped due to concerns over privacy.

Maya Mirchandani, Senior Fellow at the ORF and Assistant Professor at Ashoka University writes in an article, “Arriving at a regulatory mechanism is unlikely to be easy — a fact that is evident in the ongoing global debate, as different national governments cite their own legal frameworks to set precedent and seek control. But as hard as it may be, any regulatory framework that evolves will necessarily need to ensure that it not only protects the right to free speech in a democracy, but equally if not more so — creates safeguards and curbs against the impact and the process of online, social media amplification of hate speech that can lead to offline, real world violence.”

(Cover: Shifuji Shaurya Baradwaj))