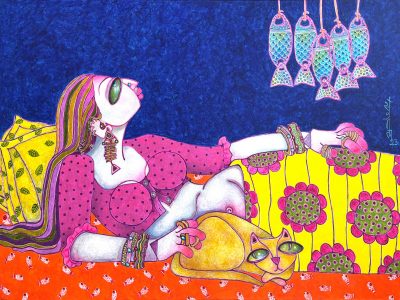

The latest exhibition at India International Center showcases Japanese woodblock prints with subjects that include famous prostitutes, kabuki actors, and erotica

Bringing to us one of the most important genres of art of the Tokugawa period (1603–1867) in Japan, here’s an exhibition of Japanese woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e or “pictures of the floating world”.

Aptly titled “The Floating World of Ukiyo-e Prints”, the Ukiyo-e were woodblock prints that depicted aspects of the pleasure quarters (euphemistically called the “floating world”) of Edo (modern Tokyo) and other urban centres. Common subjects included famous courtesans and prostitutes, kabuki actors and well-known scenes from kabuki plays, and erotica. The pleasure quarters, or yukaku, were popular gathering places for the chonin, or urban working class.

Ukiyo-e also includes paintings done by brush but in general refer to Japanese woodblock prints. The techniques used in woodblock printing were imported from China and used for printing Buddhist scriptures and their illustrations. Beginning in the 1660s, artists began to use the technique for single-sheet, stand-alone prints, rather than just text illustrations. The artist Hishikawa Moronobu (1618-1694) was the first to make a single-sheet print, triggering rapid progress in woodblock printing.

Early ukiyo-e were referred to as sumizuri-e (black ink prints) and were printed on washi paper with sumi (black ink). People began to want prints with colour so tan, a pigment made from sulfur and mercury, was used to paint colours onto the prints. These were called tan-e. By the mid-eighteenth century, artisans were able to make up two- and three-color prints.

Making ukiyo-e is a collaborative process. First, the publisher commissions a painter to create the original design, called a hanshita-e, by painting it on paper with black ink. After the painting was passed by the censors, it was pasted onto a block of wood and carved by the carver, and finally, printed by the printer.

At the time, the publisher played an extremely important role. One renowned publisher, Tsutaya Jūzaburō (1750-1797) discovered and employed such talented painters as Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), and Tōshūsai Sharaku (active years 1794-1795). Ukiyo-e were sold by special shops called ezōshiya, or by street hawkers or peddlers who handed them over to customers rolled up in cylindrical form, similar to the way in which posters are sold today.

Ukiyo-e made popular souvenirs of Edo as they were not heavy or bulky. They were not unseated from their position of popularity until the invention of photography in the nineteenth century.

The exhibition is on display at the website of India International Centre till May 9