East Delhi does not even have basic facilities like drinking water and safety as Patriot discovered during a visit on the day the government announced its success in launching an anti-satellite missile

Educated and uneducated, employed and unemployed, young and old – most of the people living in the urban villages of East Delhi are very familiar with the word ‘survey’. Yet the living conditions in these localities do not quite reflect any improvement. Scenes of grotty impoverishment seem to be stuck in time for the past five decades – even as the country gears up for its 17th Lok Sabha elections.

A pungent foul smell greets you much before you step into the old Seelampur village that falls under the Gandhi Nagar assembly constituency. The smell, courtesy of the almost 40-feet wide open drain has just about everything floating in it — from faeces and plastics to e-waste.

Flanking the entire stretch of the open drains are houses, buildings with shops in the ground floor and makeshift homes, all crammed up in small spaces. Walking through the criss-cross of narrow lanes, enough for just a two-wheeler to pass, it seems like a region that is farflung from the Capital, instead of part of Delhi.

Flanking the entire stretch of the open drains are houses, buildings with shops in the ground floor and makeshift homes, all crammed up in small spaces. Walking through the criss-cross of narrow lanes, enough for just a two-wheeler to pass, it seems like a region that is farflung from the Capital, instead of part of Delhi.

Here, the road has been left half constructed and the residents lack necessities like drinking water. The pipes that supply water to their homes run parallel to the drain that joins the open nullah. On several occasions, the tap water appears brown, red and even a dirty shade of green – all contaminated with the drain water. This leaves them with no other option but to buy water, which costs them around Rs 500 a month.

“We don’t have any other choice. We can give our children less food but how will we manage without water in this heat?” questions Anguri Devi, who has moved here after marriage and has been living here for the past 20 years.

The open drains are clearly a breeding ground for mosquitoes that are carriers of dengue, chikungunya, malaria and other diseases. Devi is in constant fear that her children will get fall sick due to the contaminated water.

Forget drinking, the water smells so bad that one even hesitates to wash hands and face with the tap water, point out distressed residents. But it seems that the people are almost inured to the perpetual smell now. None of them can be spotted covering their nose or scrunching their face from the putrid smell while walking across the foot-over bridge, right over the open drain.

The situation worsens when it rains. The water from the rain overflows and the filth clogs up the narrow streets and enters their homes too. “Only then they come and clean the drain, but that too happens once in two years,” says 85-year-old Mahipal.

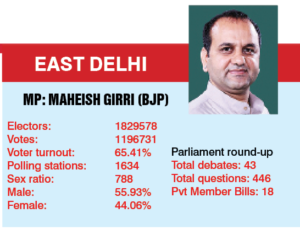

Sitting on a cot outside his home, he is joined by his neighbours who point out that the ‘irresponsible government’ always keeps making empty promises. They recall seeing Maheish Girri, the current MP of East Delhi, only once in the area during the last five years, that too for the inauguration of a park.

“We keep hearing that the government has received Rs 10 lakh to fix the drain but we don’t know where it goes. Why don’t they use it?” questions Mahipal.

The others quickly respond to Mahipal stating that nobody ever gives a second thought to the poor. “Hathi gayab ho jayega iss naale mein, phir bhi kuch nahin hoga (Even if one day an elephant gets lost in the drain, nothing will happen),” adds another resident, vehemently shaking his head.

Kalyanpuri: A crime haven

When you take out your wallet to pay the driver after getting down from the rickshaw at Kalyanpuri, the first thing that you will hear is — “Keep your wallet and phone inside. Clutch your bag tight.”

Known to be a den of crime, Kalyanpuri falls under the East Delhi constituency. People here have to be constantly on alert in order to keep their belongings safe. The culprit – a country liquor shop right opposite to the police station.

The distressed residents of the jhuggis complain that the lack of jobs lures most of the boys into taking alcohol and they waste their day under its influence.

“The contractors do not pay more than Rs 7,000-8,000 per month to the labourers. So, the boys start looting to make ends meet. Since there are not many employment opportunities these people end up committing crime,” says Suresh, who has been living in the jhuggi for the past 60 years. He alleges that some boys broke into his house and stole three phones.

At night, most autos and cars refuse to come to Kalyanpuri in fear of being looted. Not only late at night, the snatching and looting takes place even during broad daylight. While most of the perpetrators are from the locality itself, the residents claim that the criminals threaten them with knives openly. “They claim that they give Rs 20,000 as bribe to the police. When we go to file a complaint, the police turn us away saying, ‘Kalyanpuri ka to yeh hi dhanda hain (This is what happens in Kalyanpuri),” alleges Shanti, a daily wage labourer.

The main road is flanked by small makeshift homes that have been there for more than 40 years now. They have shifted back only a few feet — as the size of the road has increased from a small cycle lane to a main concrete road — and their displacement has been only that much.

Laal Singh, a 45-year-old blacksmith working on the street, points out to his small 7ft x 6ft makeshift home, where he lives with his wife and children. Singh somehow manages to earn their daily bread but is worried about his children.

“It is very difficult for my children to live and study here. They end up creating trouble in such a scene. Jhuggiya safai karke humko jagah de do,” (Clear out the clusters and give us a place to stay) he pleads with folded hands.

The residents are all going to vote in the coming elections and they say – “If you are striving to win our votes, at least come and hear our issues.” Yet the one thing that resonates among these people is a simple question – “Hum gareebo ki kaun sunega (Who will pay heed to our complaints?)?”