Delhi Commission for the Protection of Child Rights

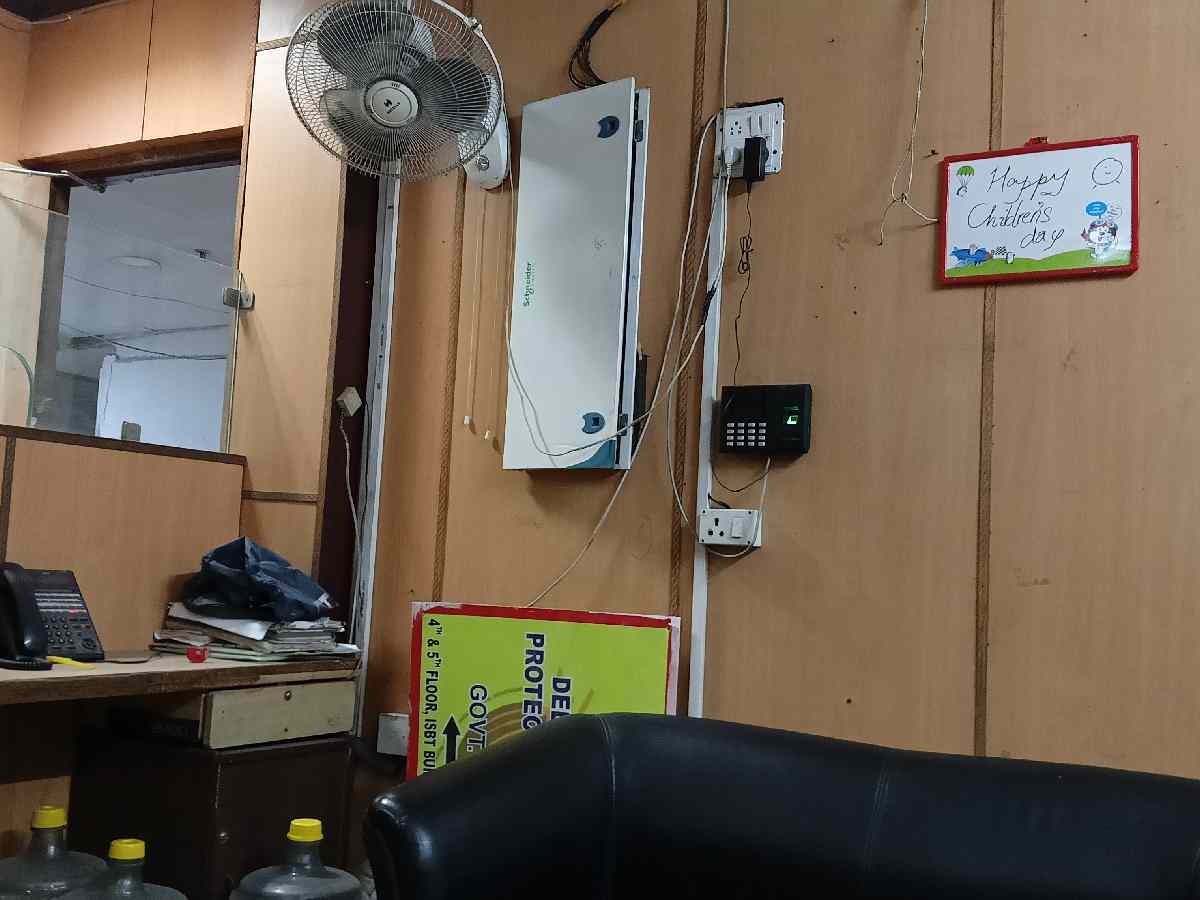

The Delhi Commission for the Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR) is today operating as little more than an abandoned office. On the fifth floor of the Kashmere Gate Inter State Bus Terminus, the sound of loose bricks and empty corridors is all that remains of a body once central to safeguarding children’s rights. Dust-laden files dating back to 2020 lie untouched. Staff members say the commission has not functioned in any meaningful way since 2023.

This breakdown persists despite the Delhi government’s hurried decision in October 2025 to appoint an officiating chairperson—just three days before the Delhi High Court’s deadline expired.

Stopgap appointment under judicial pressure

After remaining headless for more than two years, the commission received a temporary leader when IAS officer Rashmi Singh, who also serves as Secretary, Women and Child Development (WCD), was named the officiating chairperson. The post had been vacant since the tenure of former chairperson Anurag Kundu ended on July 2, 2023.

The appointment came only after repeated criticism from the Delhi High Court, which has been monitoring the matter while hearing a public interest litigation filed by the National Child Development Council. The petition argued that the prolonged vacancy had crippled the commission’s statutory responsibilities, including monitoring child rights violations, school safety norms, and juvenile welfare.

In May 2024, the court issued notices to the Centre, the Delhi government and the DCPCR seeking explanations for the delay. It noted that proposals to invite applications had been pending since August 2023 and that advertisements could not be issued earlier owing to the Model Code of Conduct.

During a hearing in July, counsel for the Delhi government said the Chief Minister Rekha Gupta, who also holds the WCD portfolio, had decided to expand the pool of candidates by re-issuing the advertisement. The court accepted this assurance and granted three months to revive the commission, scheduling the next review for November. The bench had earlier reprimanded the government for its “callousness” and warned that such delays pushed “the rights of children to take a back seat”.

Advocate Rachna Tyagi, who has been involved in the proceedings, explained that similar directions from the High Court had helped fill posts in the Child Welfare Committee and the Juvenile Justice Board. She said, “The DCPCR, however, has failed to fill any vacancies.” She added that five to seven posts had remained vacant for over two years, with only one additional secretary holding additional charge.

A commission in name only

Two months later, the situation at the DCPCR remains largely unchanged. While the officiating appointment allows for limited administrative action, key positions, including those of members, remain vacant. Officials attribute this paralysis to prolonged governmental indifference.

A DCPCR official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that none of the commission’s basic functions was being carried out. “There are a lot of unpaid dues to both the contractual workers as well as the phone bills,” he said. He explained that because the commission had been unable to clear its dues, “almost every function that we had to perform have stopped indefinitely”.

The consequences are immediately visible. Calls to the commission’s helpline go unanswered; the phone rings endlessly with no staff present to pick up. Multiple calls made by Patriot to the number listed on the DCPCR website also went unanswered. According to internal complaint statistics, the helpline last functioned on June 30, 2022. Although the number of complaints had been rising steadily before that point, none are being recorded now.

During 2021–22, the commission received 12,355 cases and resolved 5,118. In 2022–23, it received 9,372 cases till June 30, 2022, resolving 7,171. Since then, no new data has been entered. The official noted that contractual workers and volunteers had previously handled most helpline duties, but as payments stopped, the commission “lost its ability to provide salaries to the contractual employees”.

Today, only a handful of Delhi government employees remain at the Kashmere Gate office, overseeing stacks of pending complaints. According to them, they have been posted merely to formally pronounce the commission “dead”.

‘A conscious choice to dismantle the commission’

Former DCPCR chairperson and IPS officer Amodh Kanth described the commission’s collapse as the result of deliberate political neglect. He said governments rarely appreciate oversight bodies because their functioning creates more work for the administration. He pointed out that even the Delhi Commission for Women had been “thrown under the bus”.

Kanth said, “Both bodies are now operating without a proper chairperson, members, investigative teams, or expert support.” As a result, he explained, almost no cases were being registered or pursued. He said that the “dismantling of these commissions is purely a political decision” and warned that without political will, they cannot be revived. According to him, “the protection of women and children in Delhi has been severely compromised”. In practical terms, he said, “the commissions are closed”.

Kanth, who runs the NGO Prayas JAC Society, said former staff and affected families had reached out seeking assistance. He explained that many were now jobless and struggling. “As it is the cases are not being processed either,” he added.

Complainants left unheard

The collapse has also affected complainants who continue to approach the commission despite its paralysis. Social worker Rahul Ahirwar said he had submitted a written complaint regarding a school’s failure to provide books and uniforms to a student, but months later, he had received no update.

He informed, “I personally visited their office and submitted a written complaint,” adding that nothing had been done since. He explained that the commission refused to answer calls, and that even customer service staff stopped picking up once they recognised his number. He said he had been trying for ten days to learn the status of the complaint, but “no one answers”. According to him, while the child’s education continued to suffer, “they couldn’t care less”.

Also Read: Delhi sees sharp rise in suicides as Vasant Vihar death adds to mounting concerns

Another complainant, Pawan Pal, said that no one at the commission was willing to listen. “You ring them and no one ever picks up,” he said, adding that emails also went unanswered. He had been trying repeatedly to reach them but had “no luck”.

High Court frustration

In November 2025, the Delhi High Court again criticised the Delhi government for failing to fill long-pending vacancies at the DCPCR. Acting Chief Justice DK Upadhyay remarked that the government might as well repeal the Child Rights Protection Act altogether “and make everyone happy”.

Additional Sessions Judge Sameer Bajpai was hearing the interim bail application filed by Imam, seeking…

Delhi government begins stone pitching and drainage upgrades along the Yamuna between ITO and Sarai…

Four juveniles held after allegedly assaulting a Manipuri woman in a Malviya Nagar park when…

Revised system requires stage-wise documentation, periodic monitoring updates and survival tracking of transplanted trees for…

Police say the clash began after a water balloon burst on a woman, triggering a…

The court asked former Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal, ex-deputy CM Manish Sisodia and others to…