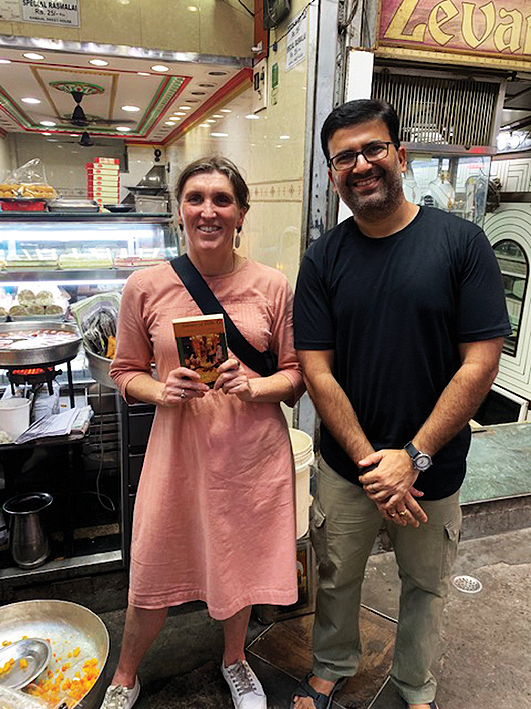

Food historian Charmaine O’ Brien was an invitee at Himalayan Echoes: Kumaon Festival of Literature & Arts in Nainital. Her travels around India have been chronicled in The Penguin Food Guide to India written after extensive travel through the country in the past 20 years. Her experiences are a guide for all who don’t know as much about how vast the spices, herbs and meats on the plate of the country are.

O’Brien is an Australian. Apart from the first-ever comprehensive guide to regional food across India, she wrote ‘Recipes from an Urban Village: A Cookbook from Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti’ and ‘Flavors of Delhi: A Food Lover’s Guide’. In her upcoming book ‘Routes of Connection’ she will see how food connects India to the rest of the world through trade in goods and ideas.

You were a university student when you first came to India. Tell us about that first journey here.

This was 20 years ago. My friend at university had told me about journeying through the mountains as he had grown up in Nainital. But the first place I landed in was Delhi. And I went oh my god, where am I?

From there I went to Agra to see the Taj Mahal, and it was one of the most awful experiences of my life. I got so hassled; I think because I was so much younger, blonder, I was a novelty.

I couldn’t stand still as I would get mobbed by whole families and suddenly would find myself in the middle of a photo and people asking me for my autograph. That was kind of quirky and cute. The thing that wasn’t was when young boys started following me.

They started off with asking where I was from and eventually asking me if I liked Indian men. It was really unpleasant and a little overwhelming. One thing India showed me was that I would not want to be famous.

By then I was questioning just being there, but I was a student and had spent about $1,600 on air fare and couldn’t possibly go back home after spending just five days.

I remembered that friends of mine had spent a lot of time in Rishikesh and they had loved it. The next day I took a bus to Meerut and then to Rishikesh. That was a good experience as it allowed me to find my feet.

I met some other people and travelled around and that’s when I started to like India and was noticing how different the food was.

Is that what led you to write about regional foods of India?

From Rishikesh I went to Varanasi and then down through an incredibly drawn out train journey to Bombay – it was still called that then. From there I went to Goa and then to Karnataka then to Rajasthan. So, I got a good overview of the food.

I was in Karnataka and went into this small restaurant. Here they had no menu, the waiter just put a big pile of rice in front of me and little bowls of what I thought was watery sauce. I though uh, what’s this? This was unlike any thali I had had before. I looked around and saw people pouring the sauces in the rice and making it into little balls. So, I thought okay I’ll do that.

And immediately I realised the flavours are like nothing I have tasted before. It really turned my head. At the end of my trip I had chaat and this too made me go: Whoa, what is this? This is amazing.

I also stayed with my friend’s mother. Just staying in their home and having home food made me realise how different it is from restaurant food. All of these experiences gave me this idea to write this book to tell the world about Indian food.

I came back the next year. And went to a friend’s wedding where I had some lovely tandoori food. That’s also the time I came up to the hills, and went to Punjab, Gujarat, which I absolutely loved.

I was travelling with a Scottish and Danish guy by this stage and the Lonely Planet had mentioned this monastery in the desert of Kutch. For dinner, they gave us a bajra roti, really fresh butter milk which I had never had before and then some sabzi which was a little sweet. This tasted so fantastic.

In another ashram, they served us sabzi and a big piece of gur and I saw they took a bite of it and then ate their vegetables. I had never had food like that.

I travelled very inexpensively. They were really backpacker trips. Some of the places I live in now and pay for — I think I would have died rather than pay that.

What do you think about Indians’ knowledge of food in their country?

People would say to me that they don’t think an Indian could have done what I did because of taste prejudice but I don’t think that’s true. I do think people have had very strong prejudices but I think that is changing. And people are being far more experimental.

I think Indian people are watching so much food TV and social media and seeing how people elsewhere in the world appreciate food from the country that now they sit up and take notice. So, there’s a lot happening with regional food.

It would be nice to see Americans stop taking Indian food and pretending that its theirs, like the whole thing about wanting to patent turmeric.

In your session at the festival, you talked about North-eastern food in India and being unable to palette them. Do tell more.

I didn’t go to Manipur or Mizoram because then my government had said don’t go there. But I went to all the other states. I loved the experience. I was so surprised about the food as it bears little relationship to mainland India.

There is Assam which has some semblance with Bengali food. Also, the unbelievable variety of green leafy vegetables and the kind of lightness to it was great.

But then there were all the fermented food and fish, oh my god, I just couldn’t eat it. Particularly Meghalaya, they had really strong fermented fish, which again for me was too much.

But in Arunachal Pradesh I had the most amazing dish I have ever had. They made fish, taking off all the flesh and chopping it up with swords, with lots of garlic and ginger and lots of fresh green herbs.

Then they took some fish frames and hung them over bamboo polls over a fire and let them get barbecued. They also picked these massive leaves from a tree and pounded them in a mortar and pestle till the juices ran off them. Finally, all these things were put together and it was so good. They call the dish pasa. It was an absolute standout dish.

Also the Singpho food, on top of Assam, has a lot of fresh herbs, lemon and barbecued food and it reminded me a lot of Thai food. So, I went through extremes of having these unbelievable things that really worked for my palette and others that I couldn’t go close to.

I went to Kohima in Nagaland. I’ll have to go back to my notes and remember all that I ate because the things that I would remember are either those I didn’t like or were really amazing. Things that were nice tend to be forgotten.

There I ate silk worm. It was like Pâté stuck inside rubber band. I had snails. I just don’t like snails. I also ate a yam dish with Akhuni (fermented soy beans) but it was really strong and I couldn’t eat it.

And then dog meat. This was all planned for me. I was asked beforehand if I would like to try it. And I said okay. So, when we got to the home where the person was cooking for me, she showed me the dog meat.

As she was cooking it, she said it smelt really good, and asked me to take a whiff. I knelt over and smelt it and oh my god, that smelt really awful.

Keep in mind I don’t like eating lamb in Australia as it has a really strong smell. As she was cooking it and poking it with a spoon she said “Ah it is a bit tough, must be an old dog”. And I just thought to myself: No, I cannot eat it. When she served it, I said I’m really sorry, that it was so interesting for me to learn that but I cannot eat it, I have a pet dog. But they had a pet dog as well. That was a meal that really stood out for me. I’m not judging it.

In your session at the festival you also spoke about how Indian homes are depending more on ready-to-eat, processed food, and ordering in. You pointed to women increasingly joining the workforce.

It’s a wicked problem, and I’m not saying women should stop working, but men could cook more. Women have gone out into the workforce in India but through my observation, they are still expected to provide food. Even in Australia I have female friends, they work really hard, often making more money than their partner but they still do the cooking at home.

I have noticed now that a few people’s husbands cook as they like to cook. But I think the turn to convenience food in India is unstoppable.

The labour of women has kept the domestic food system happening and now that women are putting their labour into paid workforce the labour of food is being outsourced to more commercial enterprises.

My concern with the supermarket is packed food. India has been a very resource conservative country and it hasn’t been a country with much packaging around. So now you are getting all this packaging you get all the 600-700 million people using packaging you have an even bigger waste problem happening. That is scary.

The other things that supermarkets do is show us all this food, and it may seem as food heaven but it has actually narrowed our food choices. You get strawberries all year round or watermelon all year round but it has no taste.

We grow mangoes in Australia and get them around the summer. But now they are starting to extend the season by getting it from Thailand and over time it will become available all year round. The things that are native will stop being produced and supermarkets will stop stocking them. So, commercially found food actually narrows the food down.

Youth shot dead by bike-borne attackers while returning from marriage function; police recover cartridges, begin…

Arunachal women allege racial slurs and humiliation by neighbours over repair work dispute; police register…

The magistrate said the probe reveals that multiple associates could be absconding, which could tamper…

The cylinder blast injured six police and fire personnel deployed at the house where a…

Multiple operational teams have been deployed to probe the case. Crime and Forensic Science Laboratory…

The initiative focused on a victim-centric approach and aimed at strengthening public trust through proactive…