Remember Bhuvan? That’s the peasant from Champaner who accepted the challenge from an Englishman to win three years’ tax exemption as the prize for winning a game of cricket.

Albeit a fictitious character in the movie “Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India”, Bhuvan’s team embodied Indian cricket for long — playing more for passion, love and pride devoid of the financial windfall. That was symptomatic of Indian cricket before the turn of the century — a game short of cash, under the tyranny of state-owned Doordarshan, and without the grandiosity of IPL.

Cut to 2018, where Indian cricket has more than Rs 30,000 crore ($4,600 m) in its coffers secured for the next five years, before pitches are laid out, coins flipped, and balls bowled. There is reason to cheer and celebrate such a phenomenon, and one may label the state of Indian cricket as: in safe hands of well-functioning machinery, outstanding control and global dominance.

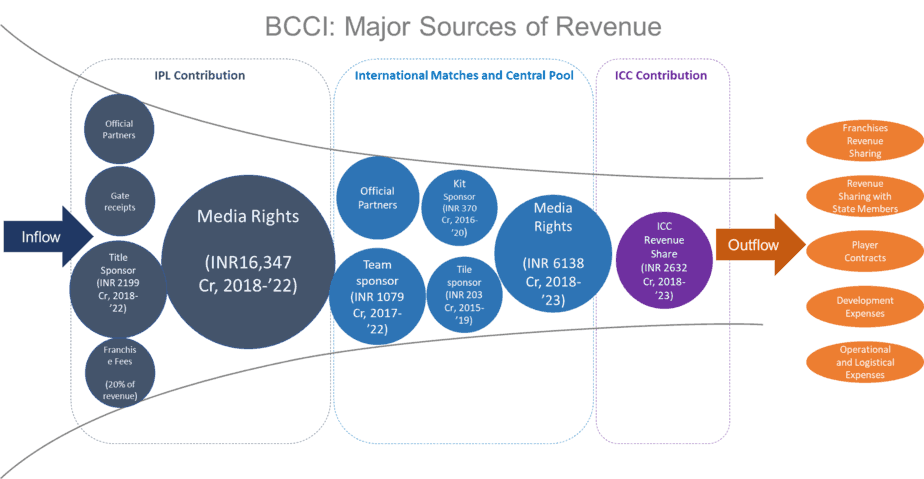

The major sources of BCCI’s revenue are media rights, sponsorship deals (title and team) and official partners. Money is spent in sharing revenues with the IPL franchises, different country boards (where IPL players come from), BCCI’s state members, developing infrastructure, paying the players and more.

It is self-explanatory that through massive funding, broadcasting partners and a few corporates are playing a pivotal role in upholding Indian cricket. With all this money being thrown at the game, what does it offer to its fans? What does it do to the balance of the game? And, has more money benefited the sport?

‘Selective’ broadcasting

It is known to many that the BCCI, like the ICC and other boards, follow specific cycles to auction broadcasting rights. Star India owned such rights for IPL (2018-22) last year and India’s home international (and domestic) matches for 2018-23.

For an ordinary cricket fan, change in BCCI’s broadcasting partner may not be a big deal. In fact, broadcasters coughing up more money to go omni-channel make consumers merrier to an extent. Options to watch it on multiple devices, in various languages, on the go are a few of them.

But such pleasures come at a cost.

Monthly, six-monthly, annual DTH/Cable subscription charges are of course there to be paid. Concepts of five-minute delayed ‘Free’ live feed are extinct and an annual ‘All Sports Pack’ subscription fee is a must to go digital. Monthly data packs must be renewed, and more and more commercials must be consumed.

In paying for — what the broadcasters call — ‘more choices to enjoy the game’, an average fan should not mind much.

Do cricket lovers need to pay extra prices for the carnage that happens in an e-auction room? Do they need to share the struggle, suffering and scourge of the bidder, the winner, the official broadcasting partner? Would the wrath of scrupulously laid out metrics by the broadcasters — net present value (NPV), return on investments (ROI) and the benefits from optimised economy of scale—miff the fans?

Yes! For the power the broadcasters wield, and the capacity they have developed to control cricket through over-the-top broadcasting outlays, there are more (hidden) costs to the fans than what is obvious.

Games are not only broadcast but also transported, popularised and made ‘games’ by the broadcasters. A game is not a game if one of its category is not available for viewing by millions. A series is not as important a series if parts of it can only be accessed to by those at the ground. An international sport loses its sanctity if games and series are squeezed in and snuffed out on ad hoc basis.

Unfortunately, there have been examples aplenty where the broadcasters have manipulated the game and the viewing experience. Women’s World Cup matches have gone missing because broadcasters defined our interests. Even with the (extended) legal contract, international women’s games were not televised what was apparently between the incumbent world champions and the runners-up. All-important ICC Cricket World Cup qualifying matches were cherry-picked and despotically forced upon the watchers.

There is more to this. The crooked BCCI scheduling. Towards the fag end of last year, the board had to find ways to oblige its broadcaster for the money it had pledged (for the previous cycle). Just when the year and the rights cycle neared an end, a lame series had to be housed to generate some extra cash. A time that was supposedly preserved for preparation to take on the mighty South Africans—to the true cricket lover’s dismay—was spent in registering gawky wins over a debilitated neighbouring team. All at the command of the broadcaster.

The ever-increasing ability of the broadcasters with a more splurging power to control so much of the sport — its formats, categories, schedules and modalities — is what makes high broadcasting rights frightening.

Tilted balance

There are many going gaga over an inadvertently created indicator, ‘per match value’ (total broadcasting rights value divided by the number of matches to be broadcasted over a rights cycle) and comparing it between IPL and international games. As much as the concept of the indicator the comparison (IPL vs International) is fundamentally misleading.

On the one hand, it is myopic to be blinkered by the numerator (Inflation must be adjusted, and payment schedules must be noted for the total rights value of Rs 6,314 crore) and turning full testosteronic and naïve to the denominator (102 men’s international matches across all formats. The women’s international matches, as well as the domestic games, count for almost nothing). On the other hand, in comparison of per match value between the IPL games and International competitions, we overlook a broader context.

Advertisements drive value in broadcasting. The fact that IPL deals with the shortest format of the game with each game hardly lasting four hours makes its per match ‘real value’ substantially more than an average international game for which Star India has recently won the rights for a mix of various formats. Note: an average IPL game offers advertisement time slots of approximately 40 minutes per game; an ODI accommodates ads for about two hours; and a Test match, a maximum of five to six hours over its full length.

There needs to be a discussion in a different dimension to interpreting the implications of the rights values, though. Far afield the ‘per match value’. In arranging and allowing a greater number of IPL matches than corresponding international contests (in the same time frame), the board guarantees that the T20s are the new cash cows in cricket’s economy occupying a weighty slice in the total cricketing pie. One may note, IPL’s total rights value (16,347 crore) is more than double that of the BCCI’s home games (6,138 crore). Looking elsewhere, ECB have proposed a 100-ball cricket format, and one prime reason is to entice its broadcasters (BBC and Sky Sports) as it fits well into their schedules and yet generates cash.

The cricket economy is far from shrinking. ICC’s revenue increase is substantial (from $1.6 bn between 2007 and 2015 to the expected upwards of $3 bn in the current cycle). The economy does not operate in a zero-sum game (one entity’s gain necessarily meaning other’s equivalent loss) either. That said, however, different dynamics are at play. First, broadcasters and sponsors shower more money in the shortest format and the franchise-based cricket, which to say the least, is eroding the value of international games. Second, the power imbalances among the cricketing nations are causing quakes and fissures across the cricketing world. The fallouts are many. Players respond to franchise callings over assuming national duties; a foreign board attempts to innovate an all-new format of the game; and the worried global body desperately firefights.

If broadcasting rights are to mirror reality of the modern-day cricket, the emerging portrait is that of the various governing body’s constant tinkering with the sport to induce more money into the game. From a sport of international matches to contests among the franchises, from the enduring test of class to multiple entertaining offshoots, the game has changed a lot, for money.

benefits yet to be channelised

The awe-inspiring money has brought prosperity to some stakeholders in and around the BCCI. One look at the various IPL teams show how Indian cricket has attracted talents (foreign players, coaches, support staff et al.) from across the globe. The business houses and HNWIs (High Net Worth Individuals) have made much from an expanding revenue pool.

Franchise owners are progressively looking outward and are colonising in foreign soil via team acquisition routes with both cash in kitty and expertise to run the game. Vijay Mallya, Shah Rukh Khan and GMR group all have licences not only for Indian T20 leagues but also for various other global leagues. Cricket and the expertise to manage the sport are among our few export-worthy and investment-enticing sectors.

Domestically, such wealth has also given rise to a more diverse (larger pool of players) and pluralistic (cricketers participating from various corner of the country than erstwhile oligopolistic representation) cricketing culture. The rate of development has, however, left much to be desired and well-balanced. We have a sizable number of stadiums of international standards but less of accessible facilities for the commoners. Team India is slightly well positioned with better bench strength of players but still don’t have enough numbers to manage the ever-increasing workload across multiple formats. 81 Indian players have played the game at international level across formats in the period from 2010 to 2017 compared to 79 in the 1990s: a 3 per cent increase of personnel to share a 70 per cent increase in match-day (including IPL) workload.

Today, we have board-contracted players earning more than once-labelled ‘peanuts’. But there still exists yawing gaps among international male and domestic male, as well as international female cricketers. Indian cricket has grown big in stature and magnitude but somewhat failed to create an ecosystem to nurture nations (especially the adjacent ones) to partake the game and make the sport more competitive.

The game is much more extensive than the times gone by watching it on cable TV broadcast and seeing it function purely in commercial interests. The game unquestionably needs money. Tt+ the same time, money shouldn’t be allowed to dictate the game injudiciously . The current state is, however, some distance away from reaching the equilibrium towards a long-term sustenance.

Debnath is a management consultant and writer.

This article has been re-published with the permission of Newslaundry. Read the original article on www.newslaundry.com

A case has been registered under relevant sections of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), including…

The accused, linked to a youth criminal gang, was nabbed from Bhalswa Dairy with a…

The matter came to light when a PCR call was received at Bawana police station…

The duo allegedly charged around Rs 1,000 to Rs 2,000 for preparing forged PCCs and…

The stretches likely to be affected include IP Marg (MGM Road), Vikas Marg and the…

Lodhi Colony, the DIZ Area and Sadiq Nagar—three long-standing Central government housing colonies—are set for…