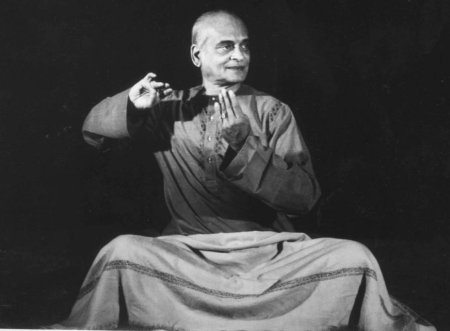

Mohanrao Kallianpurka/Narthaki.com

To start off, could you tell me how it happened that nobody wrote a book on Mohanrao Kallianpurkar (1913-85) till now? After all, he was given the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1962.

Shama Bhate: There are very few books on dance, its history and its pioneers. Our book attempts to fill this gap. It looks at the life, times and contributions of one seminal pioneer. Kathak has a strong tradition of oral and anecdotal histories. They thrive in gharana settings as gharanedaar artistes recount time after time stories of the titans from their gharana. As a non-gharanedaar artiste, Mohanrao ji would not even have that benefit of becoming part of Kathak’s oral history, and there was the real fear that the uniqueness, richness and complexity of his role and contributions to Kathak, could have been lost to us, if it were not told in a more permanent manner through a book.

Tell us about the genesis of this idea. How did your collaboration come about, among three authors based in two cities?

Arshiya Sethi: During the lockdown, after writing a poem about responsible behavior during the lockdown, I impulsively picked up the phone and made a call to a dancer I respected a lot, but did not know personally. That was Shama Bhate, a Kathak maestro based in Pune, founder of the Naadroop dance school. I impetuously asked her if she would hear my poem.

When she appreciated what she heard, I gingerly requested her to try a choreography on it. Then emerged an amazing dance piece by the Naadroop dancers, presenting Shama Bhate’s choreography as a digital choreography called “Shubham Bhavatu” that clearly stated: “This is a lockdown, not a lockup”. Its energy was contagious and served as a wakeup call to get out of the morass!

This was destiny at play. In our ensuing conversations, it came to be that she was as junooni (passionate) as I was about a dancer of yore who was now no more, and had single-handedly organised a seminar to mark his centenary, some ten years ago, when many of the stalwarts who knew him were still alive.

I have never seen Mohanrao ji dance, although I have been watching dance since I was 10 years old, which is more than five decades now. I was introduced to his work by Subhash Chander, now a Guru at the Kathak Kendra. When Subhash was still a young struggling dancer, I chanced upon him, saw him dance and knew I had stumbled on a goldmine. He dances in the distinctive style of his Guru. I asked him to teach my niece and also worked with him on presenting a paper titled God lies in the small things, which was on Thaat — one of Kathak’s distinctive intraforms. His demonstrations were perfect, pointed and poignant. I knew I would return to writing on Kathak.

Was the research and writing of this book a difficult process or a smooth one? After all, it is always easier to establish rapport when you are face-to-face.

Shilpa Bhide: Writing in the time of Covid had its unique challenges: there were both deterrents and catalysts. Covid was a deterrent because we could not travel, access libraries and other archive collections. What acted as a catalyst was that we knew that if we didn’t act now, we would have had an even smaller history and story to share, and would have lost an opportunity to order the historical line and generate authentic encounters with the past, for future generations. As it is, during the interviews, sometimes even before we could reach the appointed date, we tragically lost an informant. Sometimes we lost them between Interview 1 and Interview 2. It required a steely resolve to persist despite the various waves of Covid, but we remained determined, convinced that forgotten pasts lead to forgettable futures. Both Shama Tai and Arshiya Didi set a strong example.

Kathak is generally associated with north Indian gharanas. So how did a South Indian from Karnataka, based in Mumbai, make a mark, that too as a non-gharanedar?

Arshiya Sethi: The book is about the man, his community, the times and his contributions. In the 1930s, when Mohanrao Kallianpurkar, coming from a prestigious Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmin family, wanted to learn dance, no man from a non-dancer family was learning dance. For women, there was already a strong stigma associated with the art of public dancing. But for men, dance was not only repugnant, but also something only a particular type of woman practised. This motherless young man, dependent on his uncles and aunts for support, managed to learn dance and stay with it all his life. This is reason enough to be galvanised to write this story.

At a time when there is an erosion of Guru Bhakti, Mohanrao ji, naturally a tall man, stood even taller, because of his unstinted Guru Bhakti. He learnt from two gharanas, and several iconic Gurus. He managed to win the blessings and confidence of all of them, due to his innate qualities. But possibly it was the immenseness of the talim that he received from the masters of yore, that distinguishes him from others of his time, for an unmatched breadth of learning.

So was he a classicist or was he open to modernisation, and innovation?

Shama Bhate: Oh, I would say he was a classicist who was for innovation, modernisation. On one hand, he innovated within the boundaries of tradition, composing different variations of the same bandish, e.g. the myriad versions of the popular aamad ‘Dha Ta Ka Thunga’. On the other, he experimented with new themes, forms of literature and music that were never before used in Kathak, like the Geet Govind, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Kalidasa’s Meghdoot, and even Vedic rchas that he choreographed. All this without compromising its classicism one bit. He was a firm believer in and practitioner of tradition, but pushed its boundaries during his lifetime through his multi-dimensional work.

Mohanrao ji drew up a syllabus which is being taught at many universities, including MS University Vadodra, Banaras Hindu University, Khairagarh University and Hyderabad University. Do you believe that Kathak traditions will stay alive through practice or will future generations only learn about it in museums and books such as yours?

Shilpa Bhide: The word tradition itself signifies something that continuously flows, accommodating new streams, changing course at times, but flowing nonetheless. I truly believe that Kathak traditions will live for generations to come through practice. The fact that the syllabus he drew up is still being taught at so many important institutions is proof enough that the seed he planted continues to grow and be relevant. Stories like his will inspire many generations of dancers and pioneers will keep paving newer avenues for Kathak through their practice, just like him.

In one sentence, what would you say is unique about your book?

Shilpa Bhide: It is the first book on him and also the first book on Kathak with a cloud storage that allows the reader to view videos of his dance, pictures, writings etc. through QR codes, making it a rich audio-visual and textual experience for the layman reader and an important point of reference for the serious scholar of dance at the same time.

Non-Gharanedaar: Pt Mohanrao Kallianpurkar the Paviour of Kathak.

Publisher: Sterling

Price: Rs. 495/-

Pages: 200

Doctors at Fortis Escorts Okhla performed a minimally invasive balloon aortic valvotomy within the critical…

Wedding planners in Delhi warn catering costs may rise by 10–20% due to LPG supply…

Delhi Police arrested 40 people and apprehended a juvenile during an overnight crackdown in Rohini,…

A three-day Bhakti Sangeet devotional music festival will be held at Central Park, Connaught Place,…

Fears of an LPG shortage have triggered a sharp rise in induction cooktop sales in…

A 26-year-old man was arrested in Delhi’s Burari for allegedly possessing an illegal firearm and…