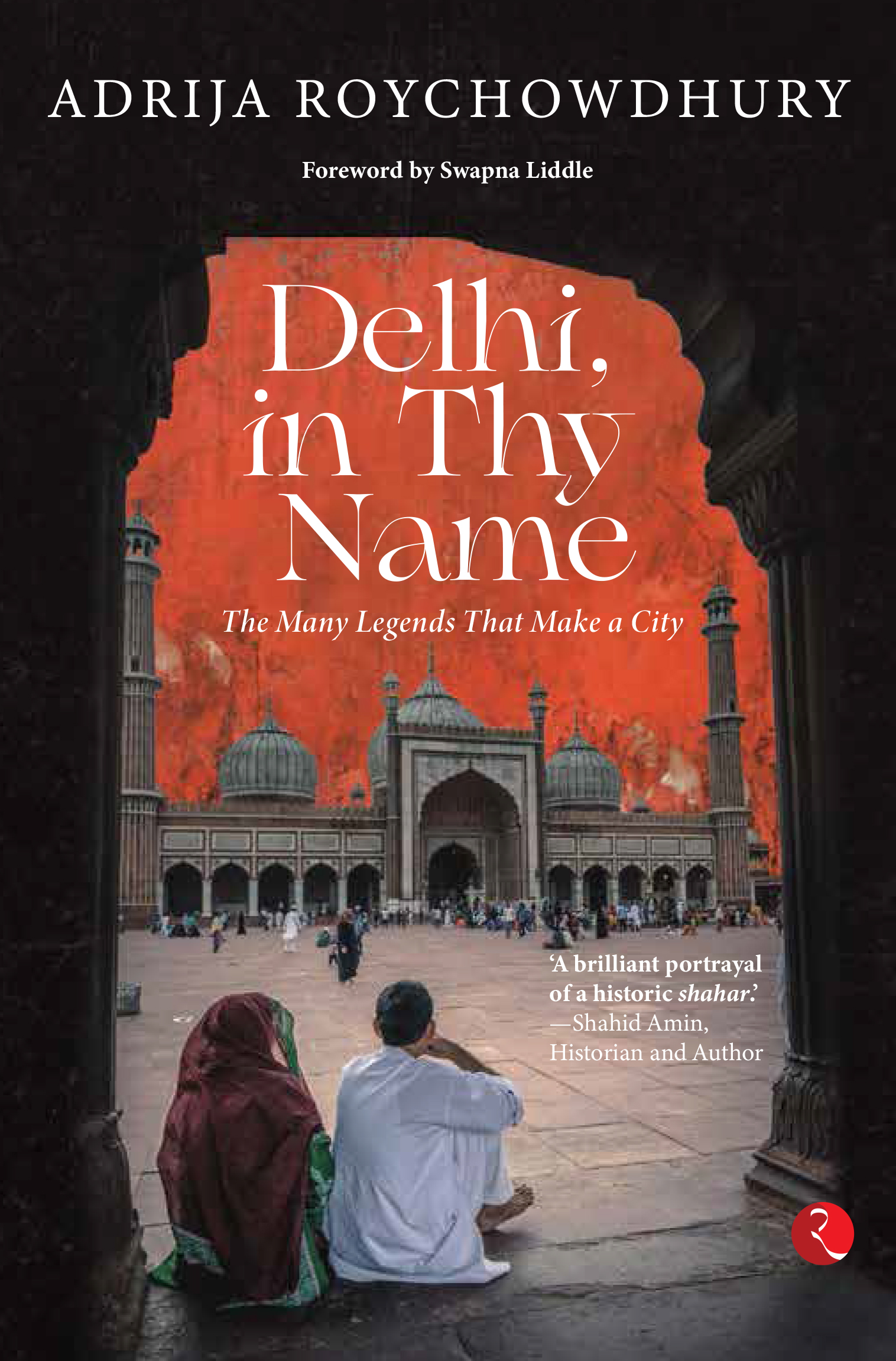

When authorities across the country are on a name changing spree that could potentially wipe out the whole history behind them – there is a need to salvage history behind the names of streets, colonies, shops, intersections and towns. Delhi in Thy Name, by journalist Adrija Roychowdhury is one such fine attempt at tracing the history of a shehar (a large human settlement).

Apart from being a historical city, Delhi is a city that chronicles the cosmopolitan character of all the people who call it home. Historians, academics, novelists, and even travelers have written about Delhi and its beauty.

Roychowdhury’s book is a journalist’s ode to this city. The book is divided into six chapters dedicated to different regions of Delhi – Saket, Chandini Chowk, Shaheen Bagh, Pamposh Enclave, Chitranjan Park, Connaught Place. And with a deeply engaging narrative coupled with journalistic style, which is quite readable, made this book a good tea-time read.

The most interesting chapter in the book is on Chandini Chowk. And even though a lot has already been written about old Delhi and its history in novels, travelogs, academic books, Roychowdhury very prudently dug out stories that will fascinate readers. She divulges stories behind the naming of Delhi’s Chandini Chowk and the surrounding areas.

Talking about a small alleyway near Jama Masjid Road called Lattu Shah Ki Gali, she writes “It is hard to tell who Lattu Shah was, but residents of the place will tell you that he was a dear friend of Shah Jahan, almost like a brother. No historical source actually mentions a friend of Shah Jahan by that name. The renowned chronicler of Delhi, R V Smith noted that this street was named after a saint associated with lattus or spinning tops, but no one knows why.”

Talking about Saket, which is another name of Ayodhya, she says it is an interesting case. This area is dominated by islamic history. But, “Among the multi-storeyed buildings and wide tree-lined boulevards of Saket, it is hard to come across any resident who is visibly from a minority community, except for a few Sikhs. The absence of Muslims among the residents is rather odd, considering the fact that there are multiple mosques and a madrasa in the area, as well as the fact that the adjoining Hauz Rani is teeming with a majority of those belonging to Islamic faith.”

The Bengali community in Delhi is quite visible and Chittaranjan Park area is so integral to the culture of Delhi’s Bengalis. In a chapter about Chittaranjan Park, she writes, “East Pakistan Displaced Persons Colony (EPDP) was a fresh phase in the history of Delhi’s Bengalis. Hitherto, though the community existed in large numbers in certain neighborhoods of Old Delhi, there was no one area which was just defined by Bengalis. EPDP colony became that space—a slice of Delhi that was completely Bengali.”

Delhi is a center of various protests. In the final chapter Roychowdhury traces how Shaheen Bagh became a face of the political struggle of Muslims in India and what it meant to residents of Shaheen Bagh.

A remarkable thing about this book is that it does not bore the reader and is easy to process. However, Roychowdhury gets carried away in a few instances. In a chapter about Pamposh Enclave, a place inhabited predominantly by Kashmiri Pandits, she dedicates this chapter to the history of Kashmiri Pandits and their exodus from the valley. Which is quite insightful but goes off topic. However, It has been common with non-fiction books – when an author conceptualizes a book and divides it into chapters, they don’t necessarily have a content for all of the chapters, so they opt for fillers. Roychowdhury seems to realise these constraints so she interviewed people and journalists like Rahul Pandita, which fits well in the narrative of this book.

Interestingly, in the book Roychowdhury also explores the urge to salvage history behind these names, “I am forced to wonder that hundred years down the line, if history of India is written, how would the naming of Ayodhya and Pryagraj be recollected? Would the story of Lord Ram wipe away multiple stories that went into making Faizabad?” Ayodhya was a town in Faizabad district, until November 2018 when the Uttar Pradesh government changed its name to Ayodhya.

She also discusses how it can be difficult for journalists to document the changing landscape of the capital due to a lack of support from the authorities. Roychowdhury in a chapter about Saket talks about this problem. She writes about DDA, “As a journalist covering Delhi, I have often found myself exhausted, on the verge of despair, having to beg officials from authority to have a word with or get a quote from.”

And though journalists seem to be guilty of being oblivious to Delhi’s soul with few having explored the city’s changing contours and culture, given that all major media houses are based in Delhi – bloggers and YouTubers document it more vigorously than journalists. Roychowdhury’s book does a good job of taking readers on a journey of names.

Delhi Police arrested 40 people and apprehended a juvenile during an overnight crackdown in Rohini,…

A three-day Bhakti Sangeet devotional music festival will be held at Central Park, Connaught Place,…

Fears of an LPG shortage have triggered a sharp rise in induction cooktop sales in…

A 26-year-old man was arrested in Delhi’s Burari for allegedly possessing an illegal firearm and…

The 7th Habitat International Film Festival will screen 67 films from 18 countries at the…

A domestic dispute in Delhi’s Seemapuri turned fatal after a man allegedly pushed his mother…