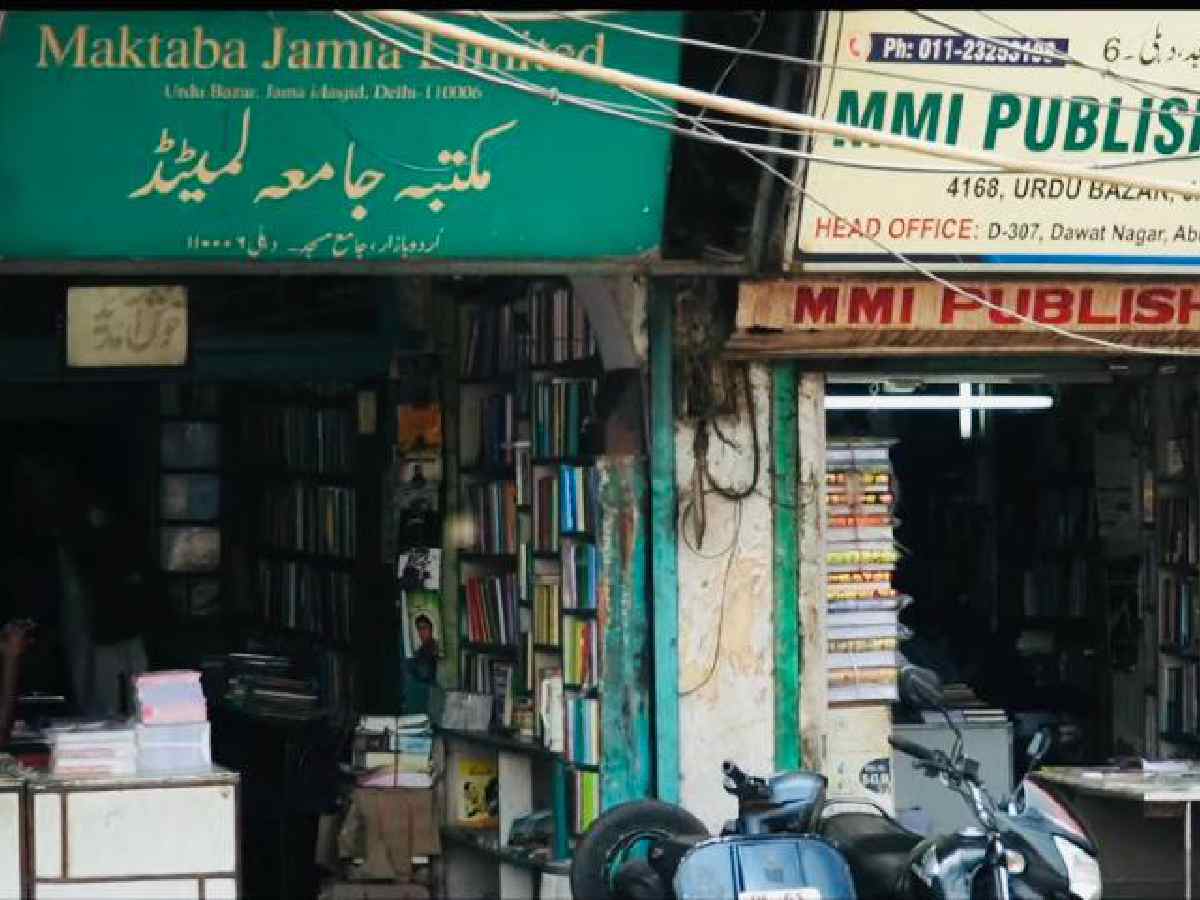

In a quiet corner of Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar, amid fading signboards and shuttered shopfronts, a few bookshops still cling to life. “There was a time when you couldn’t walk through this lane without brushing against stacks of new titles,” recalls Mohammad Arif, who runs one of the last Urdu bookstores near Jama Masjid. Today, he says, the crowd comes for kebabs, not books.

Once the nerve centre of Urdu publishing in India, this stretch of Old Delhi is now a ghost of its former self. From the 1950s through the 1980s, presses here and in cities like Lucknow and Hyderabad churned out novels, ghazals, essays, and children’s stories by the thousands. Today, those presses lie silent.

Publishers estimate that Delhi alone had over a hundred Urdu publishing houses in the late 1990s. Barely twenty survive today. Print runs that once reached 2,000 copies now struggle to touch a hundred. Many publishers have shifted to a self-financing model, where writers pay for printing and sell copies within their own circles.

A senior Urdu editor who runs a small press in Ballimaran says the business is no longer sustainable. “Even libraries and universities don’t buy Urdu books in bulk anymore,” he explains. Without institutional support, there is little hope of survival for small publishers.

A market in decline

The collapse of Urdu publishing mirrors a wider crisis facing the language. With fewer schools teaching Urdu, generations have grown up unable to read the Nastaliq script. In Delhi, once steeped in Urdu conversation, the language now survives mostly through cultural events or nostalgic poetry gatherings.

Government bodies such as the National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language (NCPUL), the National Book Trust (NBT), and Sahitya Akademi still commission select Urdu titles. But publishers say these initiatives cannot compensate for the shrinking general readership. Urdu critic and academic Shafi Saliq puts it bluntly: “We’ve gone from being a living language of literature to a language of archives.”

Urdu Bazaar tells that story most vividly. Once home to over 50 bookstores, it now has barely five. Many former publishing outlets have become eateries or travel agencies. Arif says there is still affection for Urdu, “but not enough readers. We sell more poetry calendars than books.”

Also Read: No rain after Delhi’s cloud seeding experiment, only more questions

Hope in new formats

Yet amid the decline, a quiet revival is taking shape. Rekhta Publications, part of the Rekhta Foundation, has emerged as one of the few success stories. With a catalogue of over 170 titles, it publishes both classical and modern works, featuring poets from Ghalib and Faiz to contemporary voices.

To reach more readers, Rekhta has begun releasing books in Devanagari and Roman scripts. A foundation spokesperson says their mission extends beyond publishing: “We’re preserving memory, identity, and a shared literary legacy that’s at risk of being forgotten.”

Digitisation has opened another front in Urdu’s survival. Online platforms and literary festivals such as Jashn-e-Rekhta, Jashn-e-Adab, and the Urdu Heritage Festival have brought the language to younger audiences. Many may not read the script but connect with Urdu poetry through transliteration, videos, and social media.

Salim Saleem, Editor at Rekhta Foundation, says the industry is changing for the better. Market trends, he explains, are shifting as books reach readers more easily through digital promotion. Publishers today, he adds, are more professional, offering royalties and seeking authors’ consent before publication. “This evolution has increased the sense of responsibility on both sides, for the author as well as the publisher,” he says.

Dr Md Mobashshir Husain, who writes under the name Khalid Mubashshir, Assistant Professor in the Department of Urdu at Jamia Millia Islamia, rejects the idea that Urdu is dying. He points to growing academic interest in the subject.

“For one PhD seat, there were 101 candidates,” he says. “In CUET, hundreds opt for Urdu. People who say Urdu is dying don’t see the passion of those learning it online — learning to read, write, and speak it. Look at Rekhta’s Amozish course: thousands join every month, and many of them are non-Muslims. That’s not decline; that’s renewal.”

A faculty member from Jamia’s Department of Urdu echoes that view, saying the language doesn’t need to be “preserved like an artefact.” What it needs, he adds, are new mediums — applications, audiobooks, and digital magazines — to carry its voice forward.

A deeper cultural loss

The decline of Urdu publishing reflects a fading connection with India’s literary heritage. A Delhi-based poet says reviving Urdu is not merely about saving a language but about preserving “a way of thinking, feeling, and expressing beauty that shaped generations.”

Urdu’s loss, therefore, is not only linguistic but also emotional and intellectual. It marks a diminishing of India’s composite literary identity, once defined by voices that spoke across class and creed in the same script.

Between nostalgia and reinvention

Despite its struggles, Urdu continues to live in Delhi’s air — in mushairas, in the couplets of Ghalib etched on city walls, and in the growing online community of readers discovering Manto or Rahat Indori on Instagram reels.

Poet and writer Joziea Farooq Meer sees this not as death but as transformation. The written Urdu book may be fading, she says, but its expression is evolving. “Languages survive when they adapt,” she explains. Today, an Urdu couplet shared on Instagram can reach millions within seconds — something unthinkable in the days of print.

At the same time, Meer cautions against romanticising this digital revival. Online interest, she notes, often lacks depth. The challenge, she says, is to turn curiosity into commitment — to make young readers not just quote Faiz, but read him.

Still, she remains hopeful. Every few decades, Urdu finds a new way to speak, she says. It survived Partition, censorship, and neglect, and it will survive this too, because its spirit is not bound to paper alone.

Police recovered 20 cartons containing 1,000 quarters of alcohol labelled "For Sale in Haryana Only"…

Limited-period offering at Radisson Blu Plaza Delhi Airport presents a carefully sequenced dining experience

the aerial survey was conducted between February 16 and 20 across Khyala, Vishnu Garden, Ranhola,…

Presented by Artisera at Bikaner House, the two-person exhibition brings together Ashu Gupta and Sangeeta…

Unidentified motorcycle-borne assailants fired at a Farsh Bazar house in the early hours; no injuries…

Delhi, placed in Pool H, recorded a commanding 64-42 victory over Tripura. Ashish led from…