Please note: The images used in this piece include disturbing media depictions of suicide and mental illness.

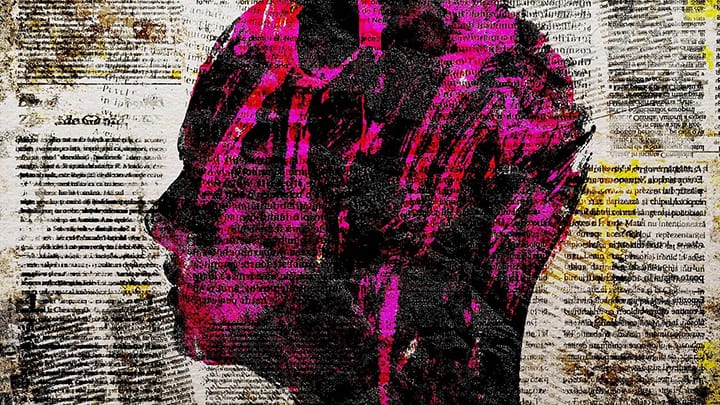

A man huddled in a corner of a room, trying to hide his face. A man with a gun to his head, finger on the trigger. An outline of a woman who has hanged herself.

These are just some of the illustrations and photographs that legacy media houses choose to accompany reports on suicide and mental health.

A lot has been written over the years about the Indian media’s problematic coverage of such news. But the recent death of the actor Sushant Singh Rajput – and the media spectacle that followed – has pushed these issues back into the spotlight. Some publications, like Gujarat Samachar, went a step further and even published images of Rajput’s body. This is exactly what happened when actress Jiah Khan died by suicide in 2013; photos of her body were splattered across the internet, and India Times went ahead and published them.

This, and the images used by media houses to depict suicide, are in violation of the World Health Organisation’s guidelines on suicide reporting, which specifically calls for exercising caution in using photos, and says “explicit permission” must be obtained from family members before using visual images.

The images also go against the Press Council of India’s guidelines stating: “All subjects should be treated with respect and dignity. Special consideration be given to vulnerable subjects and victims of crime or tragedy be treated compassionately. Private grief be intruded only when the public has an overriding and justifiable interest in sharing or viewing it.”

Additionally, experts told Newslaundry that these “representational images” are insensitive and can be triggering both for readers and the family members of the deceased. They can act as triggers for those who have experienced similar tragedies, and deliberately link mental illness with darkness, suicide, weakness and vulnerability. This is a generalisation that needs to be avoided.

Take Rajput’s death. The media unearthed details from his past, including how he had sought treatment for depression, and speculation ran wild. Unscrupulous news organisations even quoted Rajput’s psychiatrist — in a complete breach of ethics — to explain his “state of mind” and personal issues. The psychiatrist later said he had not breached confidentiality or spoken to the media.

Nishta Borah, a Goa-based clinical psychologist, pointed out that it isn’t always depression or any other mental illness that leads to suicide.

“There are a lot of factors like gender, sexuality, socioeconomic conditions, etc,” Borah said. “Also, it could be a decision taken in the spur of the moment, whereas depression is very different from that. It happens over a period of time, and can happen to anyone.”

After Rajput’s death, one of Borah’s clients had a panic attack after consuming all the news reports on his suicide. The client had a friend who died in a similar manner, Borah explained. “Such reportage becomes overly triggering for people like her, who already have a history of trauma,” she said. “In a few countries, if such content is shown, it comes with a warning. But in India, there is no such thing.”

Instead of visually depicting someone with a mental illness in their most vulnerable state, Borah said, why can’t we show them as people who are looking for something, or being listened to?

Traditionally, mental health in India is not really reported on, said Tanmoy Goswami, a sanity correspondent at the Correspondent. The only entry point for such reports is suicide, he said, as a result of which a “very dangerous assumption is made: that all suicides are a result of mental illness”.

“Until recently, suicide was a crime in India, and hence used to be covered by crime reporters,” he said, “who used to try and get every detail on the method of death.”

Goswami agreed that the best way to depict mental illness is through regular photographs of people, not to look for the most sensational image in a media organisation’s image bank. The same rule applies to suicide, where organisations need to be very sensitive in their reporting. Images must not reveal methods of death or act as a trigger.

When asked about the depiction of mental illness and suicide in media reports, Meghna Mukherjee, a psychoanalytical psychotherapist in Noida, quoted a scene from the final Harry Potter movie. Meeting his erstwhile headmaster, Albus Dumbledore, in some sort of parallel universe, Harry asks: “Is this real? Or has this been happening inside my head?” Dumbledore smiles and replies, “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

Mukherjee said she finds this scene very powerful, and that it resonates with mental illness too. According to her, the manner in which the media has reported on mental illness in the past, and on Rajput’s death in the present, has “stigmatised a lot of taboo”.

“While images may be thought-provoking or engineered to appeal to people’s sentiments, they can do something else as well. Such images often tend to reinforce the stigma of being weak and different (and not in a positive way) to the patient,” she said. “Which is why a reader with the same illness would never like to disassociate themselves, and the purpose would be futile.”

If you, or someone you know, needs help to overcome suicidal thoughts, contact: Fortis: +91 8376804102; AASRA: +91 98204 66726; The Samaritans, Mumbai: +91 84229 84528 (5 pm to 8 pm)

www.newlaundry.com

The cylinder blast injured six police and fire personnel deployed at the house where a…

Multiple operational teams have been deployed to probe the case. Crime and Forensic Science Laboratory…

The initiative focused on a victim-centric approach and aimed at strengthening public trust through proactive…

Six of the suspects have been arrested from different parts of Tamil Nadu and will…

The weather department has predicted a mainly clear sky during the day with the maximum…

The likely Rs 1,000 crore sale of the Tehri Garhwal House, former royal residence on…