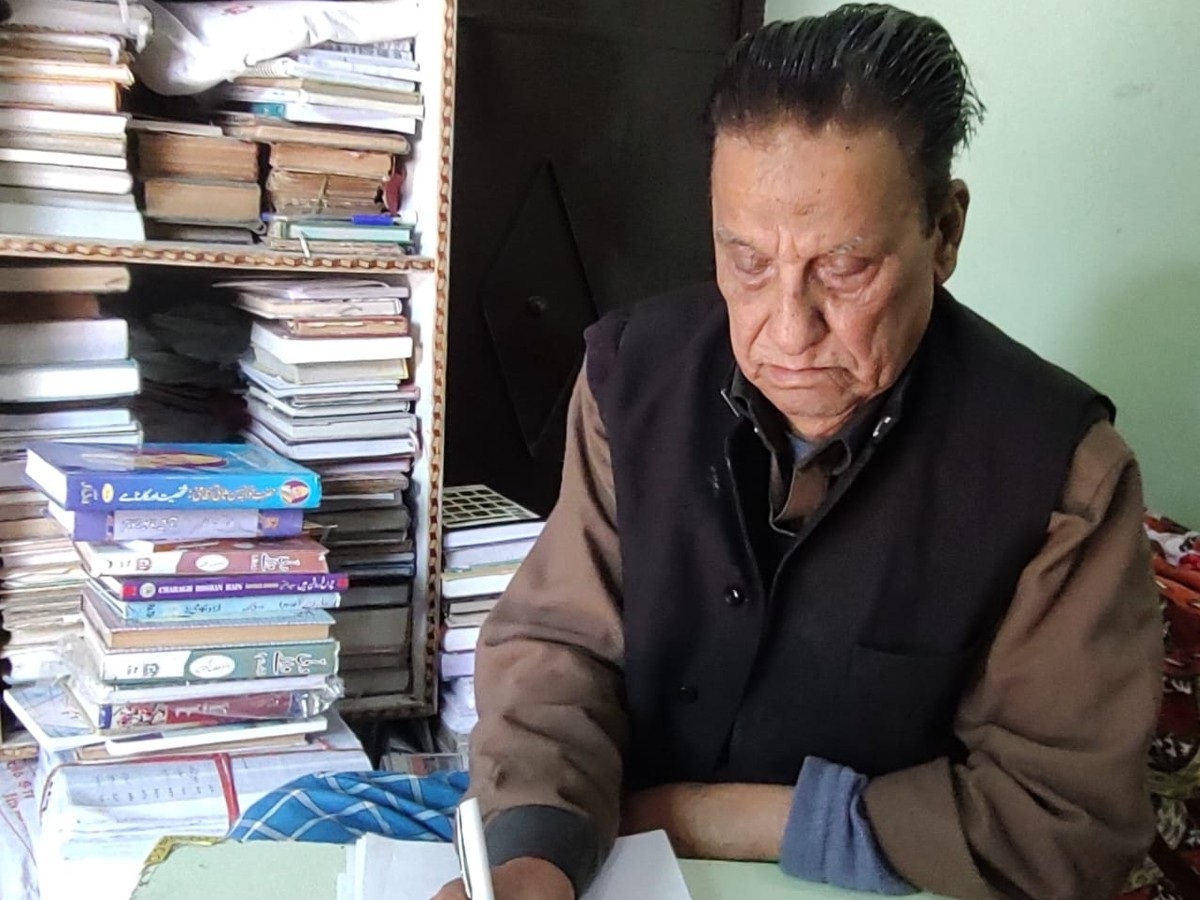

PENNING THOUGHTS: The 82-year-old Farooq Argali started writing fiction in the 1950s to earn a living.

In 1956, when writer and poet Farooq Argali, then a 16-year-old strapping man, came to Delhi from Fatehpur in Uttar Pradesh, he had his eyes set on picking odd jobs for a living.

After Argali’s father retired from the police, he tried his hand at farming but could barely manage to secure two square meals a day for his family.

Young Argali’s education had been halted in the village itself after the fourth standard. The state government had removed Urdu as a medium of instruction from government schools in most districts soon after independence and Argali, being underprivileged, couldn’t afford to enroll in an Urdu medium school.

So, he aided his father in farming and, when it didn’t come to much good, landed in Delhi.

“I couldn’t complete school, therefore getting a fixed, secure job in an office was near impossible. Even for a peon, you needed to have cleared class eighth or 10th. I had not studied beyond fourth. So, I landed in the walled city and started picking odd jobs like that of loading and unloading goods or packing them,” he says in his home in Krishna Nagar, east Delhi.

But one passion he never gave up, even as he worked as a labourer, was reading.

“I was very fond of reading right from my days in the village. My relatives used to have a trove of Urdu classics. Poet Hasrat Mohani’s younger brother was a relative. After his death, the best, or, let’s say, the most serious and rare ones, were taken away by Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-Urdu (an organisation to promote the Urdu language) in Lucknow and Aligarh. But in his house, there remained a vast body of literature and light literature as well as old files of magazines in a large number. So we managed to read those a lot. And in the village, only we had an interest in reading them. I was fond of Urdu literature. When I used to farm or take herds of animals for grazing, often I’d sit on the back of the buffaloes and read novels, even if it was drizzling,” recalls the 82-year-old who has recently compiled and edited Dilli Nama (an anthology on Delhi).

“I came to Delhi and found a culture of Urdu here. I used to go to libraries in Chandni Chowk in my free time. And to the Maratha library; I learnt to read Hindi there. Then I used to go to Hardayal Municipal Library. There was a gentleman called Bahaar Illahabadi. He was a librarian and became a sort of my older brother. I used to call him bada bhaiyya (big brother),” says Argali.

“He was very generous. Whatever book I used to place my hand on would be issued. I’d take it, read it and return it. I learnt Hindi by keeping Navbharat Times (Hindi) and Partap (Urdu) newspapers in front of me and comparing the news items. I’d translate each word into Hindi to learn the language,” he explains.

Meanwhile, he had also earned some diplomas in Urdu from Jamia, but those didn’t qualify him for a job.

Reading brought an urge to write a novel. And at 17, he wrote his first novel.

“I wrote it within six months of my arrival in Delhi. The novel was called Naye Daagh, Naye Phool (New stains, New flowers),” he says.

It came out rather quickly.

“You see, I had read so much literature that I didn’t find it hard to write. I had been reading since the village days. I was fond of reading historical novels a lot. Tirath Ram Firozpuri was famous for translating English novels into Urdu. I read Mysteries of London by George W.M. Reynolds. That uncle of mine had Reynolds’ entire set in Urdu. I’d read that whole thing. I tried to understand English literature and culture in Urdu. I used to read other translations too. The translation of Russian novels was also available in Urdu. Those used to be beautiful novels. I read the novel ‘Mother’ by Maxim Gorky in Urdu (titled Maa),” he recollects.

Like many Urdu and Hindi novel writers of those times, he was inspired by Ibn-e-Safi, an Indian writer who had migrated to Pakistan and wrote prolifically on mystery, suspense and romance.

Getting the first work published was a challenge. He went to a publisher in Old Delhi, where he was living at the time and where almost all the publishers had their businesses.

“There was a publisher called Ratan & Co. Booksellers in Dariba Kalan. They used to publish storybooks, novels and religious scriptures. They used to publish everything. So I gave it to them. I was a bit hesitant as I approached him. Told him Lalaji dekh lijiyega musavvida (Lalaji, please have a look at my manuscript). This was Naye Daagh, Naye Phool. He looked at it from top to bottom and then said, ‘I’ll see’,” he recollects.

“I didn’t go to him for the next two to three months. Then I went, scared, fearing he would say, ‘what nonsense have you written?’.

“I said, ‘Lalaji, I had given you a copy’. Lalaji got up, handling his dhoti and went inside and brought out 5-7 copies, published on a cheap, yellowish paper and soft-bound. It looked nice, as it had my name on it. Very poor type-setting (calligraphy). It was very chaalu (run-of-the-mill). He gave those copies to me and said, ‘Son, I have published it’. He also gifted me 50 rupees for it. It was liked and read and priced at baara aanay (75 paise),” he added.

“I thought, “This work is much better than loading and unloading. Besides, you get to sit on a table and a chair with a pen”. Then I started writing. Every month, I would write two-three novelettes – these would be 125-160 pages. They would be sold for 75 or 50 paise or a rupee in the market. The shopkeeper would get 33% commission on it,” he added further.

“Then I started writing novels in papers, in which they were serialised. I started writing film articles. In that era, if your writing could draw interest, it would sell like hotcakes. Gossip, romantic novels and thrillers used to be popular because there was no other form of entertainment except radio. Everyone couldn’t buy or maintain a radio.”

Argali says that reading had a huge impact on language and culture.

“Stories and tales always create interest. In those times, there used to be lending libraries. There were shops full of novels and you could borrow one for an anna or two annas a day.”

Through the sixties, Argali kept writing on suspense and romance and came out with 150-200 novelettes.

“Outside old Delhi, there were small Punjabi bastis (localities). They used to read Hindi. When I started writing in Hindi, it also started selling well. Getting published in Urdu was tough because buyers were fewer. Urdu writers were aplenty and publishers used to give importance to better writers. We were unknown writers. We never used to get good money in Urdu. Hindi writers would get huge money. For a Hindi novel, you’d get around Rs 800-1000 and in Urdu, you’d get Rs 150. Because Hindi novels sold in the thousands.”

In the 1970s, he wrote what he calls ‘hot novelettes’ under the pen name Haseena Kanpuri.

“I wrote 80 of them. But they weren’t more than 100-125 pages. Used to be sold in huge numbers. They were hot novels. The publishers had kept this fake name and said the writer lived in a brothel,” he added.

“It was my profession, I had to write as per the demands of the publishers. I wrote some good novels too in the period under my original name.”

But the emergency brought an end to all the sizzlers and started his journey into the world of serious writing.

“Post-emergency, a company asked me to write serious, social novels in Hindi under the pen name Rati Mohan. In 1980, I started doing other works like running an Urdu magazine Tezgaam (fast speed), which was started by politician Babu Jagjivan Ram, who split from Indian National Congress and formed Congress (J) and ran the magazine as per his wishes.”

Argali’s last novel was published in 1982.

He also was a key member of the Aalami (world) Urdu conference, which invited the best poets from around the world, including Ahmad Faraz from Pakistan.

“It gave me an insight into proper Urdu literature. Since then, I have made it a habit of writing on personalities who have contributed to the language, syncretic culture, independence and religion,” he says.

“I have also produced 10-12 documentaries. One is an hour-long documentary on [Bhakti saint] Mirabai, available on Amazon Prime. Another is on Lucknow,” he added.

Dilli Nama is a two-volume work which he says covers Delhi from ancient times. It was published recently.

“I have edited and compiled it from booklets or articles on Delhi written over the last 150-200 years, spanning over two volumes — from the time of Mahabharata till the era of president A.P.J. Abdul Kalam,” he explains.

“There are books from different periods — from 1865 to the post-Independent period — from where I have collected my material. Such as Aasaar-us-Sanadeed — a book on Delhi’s monuments by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan.”

He continues to write and edit.

However, like a worried elder of the house, he breathes a sigh of relief when he says neither his son nor his grandson, who are sitting next to him all this while, have become writers.

“My grandson is an engineer and my son has his own business. They didn’t become writers and for that Allah ka shukrhai (thanks to God). It had been tough making a living as a writer.”

The matter came to light when a PCR call was received at Bawana police station…

The duo allegedly charged around Rs 1,000 to Rs 2,000 for preparing forged PCCs and…

The stretches likely to be affected include IP Marg (MGM Road), Vikas Marg and the…

Lodhi Colony, the DIZ Area and Sadiq Nagar—three long-standing Central government housing colonies—are set for…

The 12-day Tribes Art Fest organised by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs in collaboration with…

The national capital recorded a minimum temperature of 18.1 degrees Celsius on Saturday, a day…