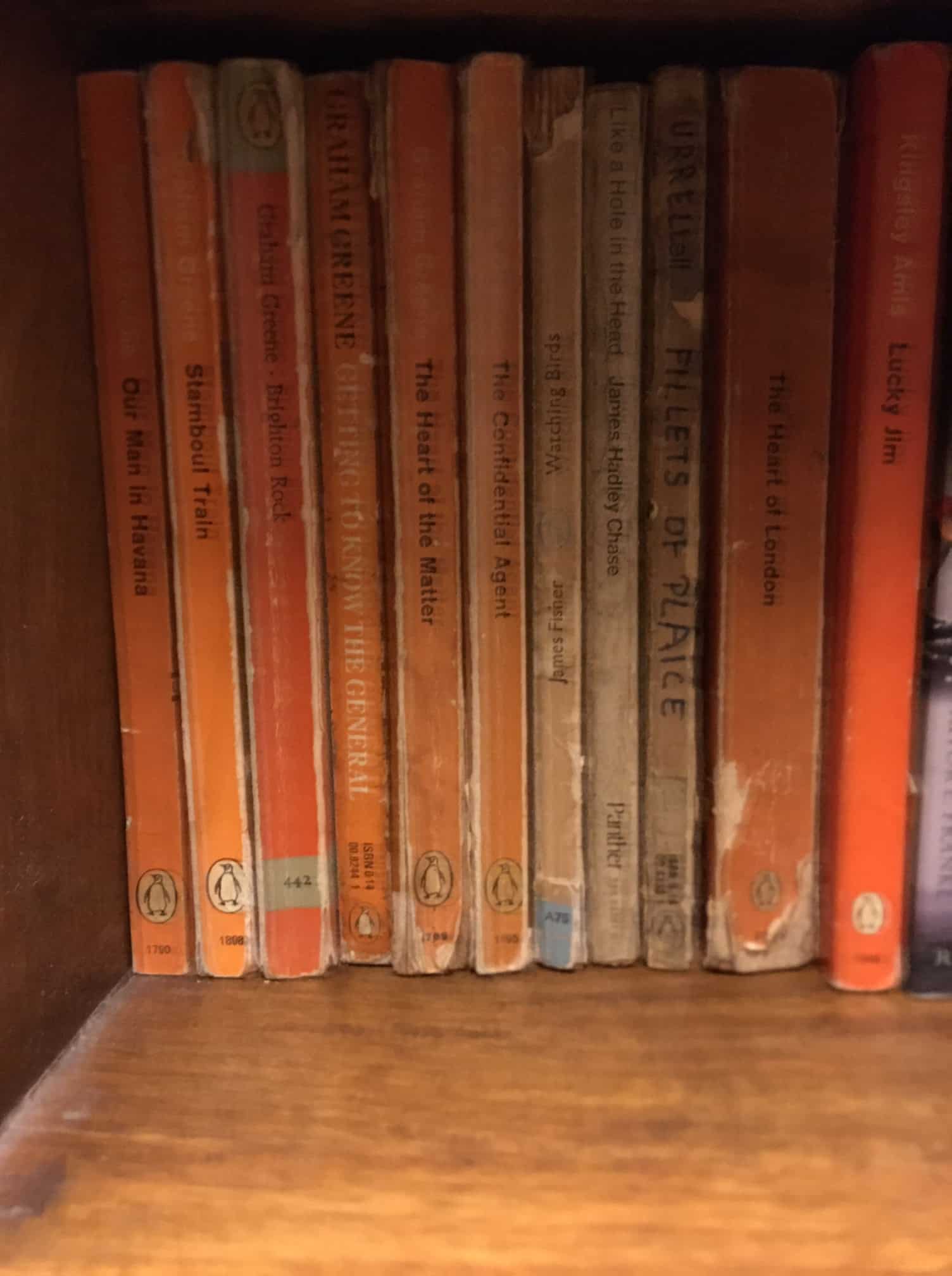

1960 print of Graham Greene novels for Rs 500

Delhi had a flourishing economy of rare old books that reached the bibliophiles at cheap prices and were sold from most innocuous places—like a pile on a footpath. The flea markets of old books, like the Sunday Daryaganj book market, are in dire straits thanks to the pandemic and strict action of the government against unorganised markets in general. Some of the famous old books shops in Connaught Place (CP) and other parts of the city, like Mehrauli, are also facing an existential crisis; very few would be able to survive.

This was always on the cards, the pandemic just hastened the process. Anirudh Sharma, in his mid-forties, is a soft-spoken intellectually inclined person, likes to describe himself as a “pen pusher” is overwhelmed by nostalgia, “There is no bigger joy than flipping through the pages of the old yellowing book on the payment.” He has been a regular at CP and other flea markets of old books across the city for decades. He’s friends with some old booksellers like the famous shop near Plaza cinema in CP, “The old man—Anil—has died and now one of his assistants takes care of the shop,” he informs.

He feels that it’s a byproduct of social distancing during the pandemic, like many things, technology has replaced this physical aspect of interaction, not just with buying and selling of books but for that matter meeting with friends or the classroom education. He considers it as “a loss of a way of life.”

There are many online forums that trade in old books, and some have a healthy following. Anirudh follows one Facebook collectors’ group that deals in old Hindi poetry books, “there has been less activity on it (in the past few months),” he informs with regret. Perhaps people are reading less or with reduced enthusiasm.

Dhritabrata Bhattacharjya, popularly known as Tato amongst friends, wears many hats, is a publisher, founded Daastaan. “The best way to demolish a business is to make it irregular,” he says. That’s what happened with the Sunday Daryaganj book market, bibliophiles who’d invariably spent Sunday mornings there weren’t sure if it’s open, their favourite booksellers winded up, and so over the next few months, people got disinterested. Though some stalls are put up in Ansari Road, not far from the original venue, they have lost their old charm. “Intellectual lot has completely stopped,” affirms Tato and he holds successive governments responsible for killing the flea market of old books.

And technology has had a profound impact on various aspects of life, and the literary pursuit is one of them. Tato asserts that even the meaning of “rare books has changed in the last two decades” as the digital version of the rarest of rare books is available. It’s akin to people paying a huge price for an old LP record because there were a limited number of copies but now with digital music available that cult following and the need to own a record at any cost to be able to listen to music is not a necessity.

Similarly, technology has democratized the access of classics, both books and music, in digital format. In fact, many of the old classics are free to read online.

“But if you look at the old book as an art object or collector’s item or a signed copy of a rare book, even scrolls.” Tato draws the distinction, “these books are not in demand as a source of information, are still very much in currency, and traded/auctioned online as an art object and not literature. They are the asset class.” He cites the example of Quran Sharif from the eighth century—one of the oldest copies—in the British Museum.

The flea markets were notoriously famous for finding banned books. It was a flea market where many got their copy of The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie, for example. Tato points out that a banned book is a successful one—opposite of the rare books—and therefore are banned to limit access to people at large.

But then there are some who are not nostalgic for the old ways as long as they get to discover books and writers. Prashant Joshi, 45, is a banker, and all through his student life purchased cheap old books from the pavement, “it used to cost Rs 10-20,” he recollects, were littered on the payment in a big pile. And looking for a book was like fishing in deep waters, you never knew what you’d end up laying your hands on.

“There was an element of surprise and zest,” says Prashant as if deep diving in the world of literature and surfacing with hidden treasure. He has many cartons full of books and possibly could open a shop for his collection of old books. He wants to part with some of his books in a way that they are read and reread, perhaps will donate it to a library.

Now Prashant employs the internet to the same effect—the wow factor of discovering something new, his favourite shop in the world is Amazon, where people are encouraged to buy and sell books.

“E-commerce in India has changed the buying habits of customers. 15 years ago, we used to regularly visit book shops and spend hours finding what we need. With online selling, buying books has become so easy that books are now one of the top-selling categories in e-commerce,” declares the Amazon website. Prashant agrees.

“Now even the pirated books sold on the payments these days are less than Rs 100,” points out Prashant, and some of them are actually cheaper online and there’s a huge pool of books to choose from. He gives the example of discovering a French author named Fred Vargas while searching for books under the broad topic of ‘European crime thriller.’ “I didn’t know about her, discovered her online,” says Prashant. He has since read a dozen books—“almost all authored by her,” he asserts.

Times are changing, reading habits are changing, and technology is changing the mode in which literature is consumed. “Going through old books in a flea market is like a sellable library curated by an erudite unknown reader,” as Tato puts it poetically. The satisfaction of buying a whole set of the 1960s edition of Graham Greene’s books for Rs 500 is a thing of the past. Bibliophiles will continue to explore old books, the only regret would be, in the past, old books also connected people, not anymore.

From neighbourhood cafes to roadside eateries, operators say the disruption has slowed or halted kitchens…

MCD invites agencies to study the feasibility of using smaller mechanised sweepers to clean Delhi’s…

The maximum temperature is expected to settle at 34 degrees Celsius, with a forecast of…

Court flags overcrowding, low occupancy and exclusion of women inmates in open correctional institutions

Doctors at Fortis Escorts Okhla performed a minimally invasive balloon aortic valvotomy within the critical…

Wedding planners in Delhi warn catering costs may rise by 10–20% due to LPG supply…