Just as the Pakistani state and society has internalised the ‘good Taliban, bad Taliban’ policy, Indian state and society seem to have embarked on the course of internalising ‘good extremist, bad extremist’ distinction.

Over the years, the public discourse has descended to a level that can be summed up as ‘my extremist good, your extremist bad’. A corollary to this is that ‘the extremist I support, sustain, sponsor and consider a strategic asset mostly for a tactical gain is not as dangerous or as big a threat to national security or social cohesion as your extremist’.

Things have reached a point where even a neutral remark or comment against extremists is quickly latched on to by everyone and read either as an endorsement or, as the case may be, excoriation of the ‘other’.

Any comparison between India and Pakistan on the issue of extremism is undoubtedly odious. And yet, a parallel is being drawn with Pakistan only to shake people out of a sense of their complacent belief that what is happening in our neighbour from hell will never happen here.

The sort of sanctimonious denial we see in Pakistan on extremism — Islam is a religion of peace, Muslims don’t indulge in wanton violence or in acts of terrorism, there is no terrorism being exported or sponsored by Pakistan etc — has slowly started creeping into Indian mind space as well: Hindus are by definition secular, there is no extremism among Hindus, Hindu terrorism is a figment of imagination, or that Indian Muslims aren’t involved in terrorism, Indian Muslims are immune from being radicalised, Indian Muslims are being deliberately targeted by the Indian state and so on.

There is a lot that Indian can learn from Pakistan, which is in many ways a living laboratory of political science. Every weird, whacky or wonky idea that people and politicians in India have ever toyed with, has been tried in Pakistan with quite disastrous results. The havoc that the military causes when it interferes in politics, the deadly cocktail that is created when religion is mixed with politics, the untenability of a presidential system, the complications caused by the obsession to hold national and provincial elections together, the perils of mortgaging your security and economic interests to a foreign power, are all examples of Pakistan’s follies that India needs to avoid.

The scenes of anarchy, lawlessness and chaos in Pakistan following the acquittal of a Christian women accused of blasphemy are the wages of succumbing, surrendering, or even getting seduced by the idea of using the forces of fanaticism.

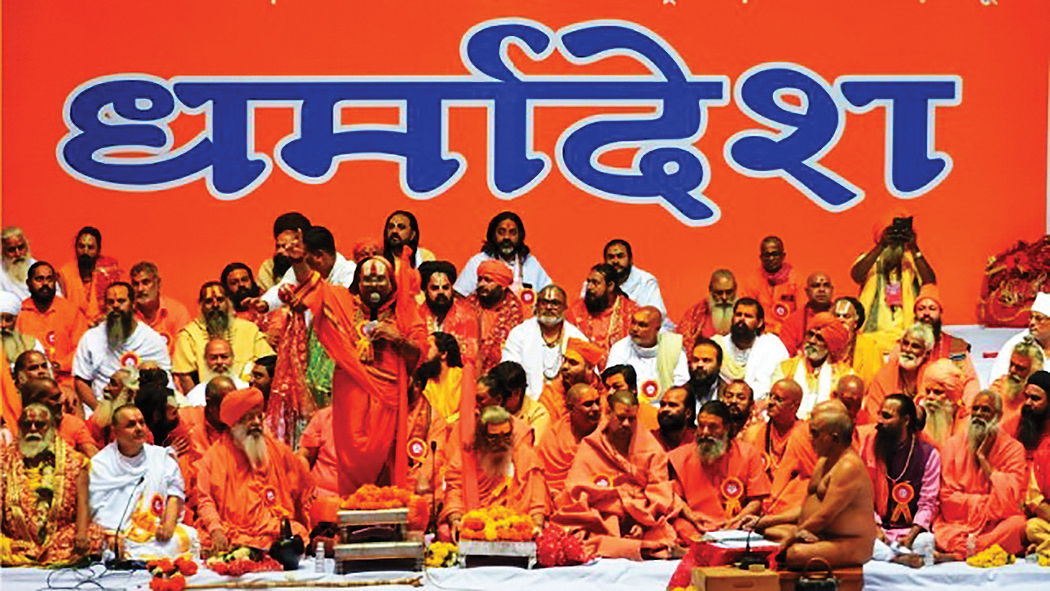

But while it is just desserts for Pakistan, it is also a wake-up call for India to not follow in Pakistan’s footsteps. Over the last few years, there is a dangerous trend unfolding in India. Fulminating fundamentalists who should have been marginalised, isolated and ignored, have today been mainstreamed and projected as leaders and representatives of their communities.

TV channels disingenuously explain this away by saying they are exposing these charlatans, but in fact what they are doing is empowering and legitimising these same charlatans.

Who has given these maulvis, muftis and maulanas or pandits and acharyas and babas the right to speak on behalf of their community? Who do they represent? What is their following? Most of these characters are incapable of winning even the votes in their own families and yet they pretend to speak on behalf of millions of people?

While earlier backroom deals were struck, conspiracies were hatched and religion was traded by these dubious characters, today TV has brought them into our living rooms and bedrooms, pitching one set of reactionary and antediluvian clerics against another set of clerics.

The idea is not to inform but to create drama, incite passions, and unleash base instincts. What is happening on our TV screens is not a debate but a demonstration of primordial prejudices.

But why blame only TV stations for the dystopian debate that has become the staple of public discourse and public policy. The dumbing down of public debate is also manifested by the proclivity to conflate issues and an utter disregard of context.

For instance, if you speak against Islamism and jihadist terror, it is assumed you are anti-Muslim. The tendency to mix up issues by equating two very different events is also rampant. How can anyone with a modicum of sense not distinguish between courts outlawing triple talaq (a social ill that affects the lives of real people) and courts forcing a place of worship to surrender its traditions (that don’t hurt anyone, don’t violate public safety or public morals).

Similarly, conflating mobs baying for the blood of an innocent woman and calling for the murder of judges, with protests against a judgement that interferes with a religious tradition that doesn’t constitute a threat to anyone’s life or property betrays an astounding obtuseness.

The point is that as a society we have started to lose the ability to set rational metrics on the basis of which we form our opinions on any issue. The result is the self-righteousness of the extremist who claims the right to defend his extremism and rationalise his supremacism, harvest the souls of people of other faiths, spite, insult, mock and demean someone else’s faith and belief system.

If you listen to one side, it would seem that communal violence and extremism started in 2002 and became firmly embedded in 2014 after Narendra Modi became Prime Minister. The sordid history of communal violence under the Congress’ watch has been airbrushed from public memory — Ahmedabad, Meerut, Maliana, Bhagalpur, Bhiwandi, Moradabad, Mumbai, it’s an endless list of communal pogroms that the secularati doesn’t even talk about.

On the other hand, if you listen to the other side, there is no problem at all with the sort of rhetoric and positions that some of the Hindutva forces take on a variety of issues and there is a needless furore over Hindutva exceptionalism and exclusivism.

The fact, however, is that neither is BJP or Narendra Modi to blame for everything nor are the forces of Hindutva completely innocent and blameless.

In the Indian polity, everyone is guilty of fanning fundamentalism and fanaticism of one sort or another — the entire Khalistan movement was fanned by the Congress party as was the Ram janam bhoomi issue. The BJP too will be playing with fire if they try to remain in power by polarising society.

They might win the election but will find it difficult to govern the country if a blind eye is turned to the activities of cow vigilantes and radicalised groups like the Abhinav Bharat. Here again, the experience of Pakistan is instructive.

It is a terrible idea to underplay the menace posed by these vigilantes and wait for them to become powerful before action is taken against them. It is better to nip these organisations in the bud because it becomes extremely difficult to crush them once they grow big.

But why blame only the BJP which isn’t doing anything that its rivals haven’t done or are not doing. The entire Lingayat controversy in Karnataka was about sowing divisions for garnering votes and out manoeuvring their political rivals.

In Bengal, Mamata Banerjee has bent over backwards to appease the most foul-mouthed mullahs and then when it seemed that this was alienating the Hindu community, tried to appease them by doling out money to puja pandals. Selective secularism and competitive communalism is something that everyone has tried to use to their advantage, even if this was at the cost of undermining national security. Why else would senior Congress leaders like Digvijay Singh and AR Antulay bat for the ISI and Lashkar-e-Taiba by fanning stupid conspiracy theories that RSS and its affiliates were behind the 26/11 attacks?

From Kerala to Kashmir and from Maharashtra to Manipur, politics is less about policies and performance, and more about majoritarian consolidation and minority appeasement. The public discourse and debate increasingly reflect this unfortunate reality.

The recent events in Pakistan should inform us of the trajectory of things to come if we don’t step back from the destructive path that we have embarked upon of using religious forces to settle political questions. Because once we bring the genie out of the bottle, mainstream it and allow it to occupy centre-stage in our public discourse and national narrative, allow mobs to dispense vigilante justice (an oxymoron if ever there was one) everything else that we need to do to build India into a prosperous and strong nation will start to take a back seat.

www.newslaundry.com

The likely Rs 1,000 crore sale of the Tehri Garhwal House, former royal residence on…

On the principle of 'Sarvajan Hitaya, Sarvajan Sukhaya' -- Welfare for all, Happiness for all…

With hundreds reported missing in Delhi this year, this guide explains how families can use…

The case came to light after a 35-year-old woman from Panipat alleged that she had…

During the investigation, CCTV footage helped identify the suspects, according to Delhi Police

The launch took place during the inauguration of the Delhi Police Exhibition Hall at Connaught…