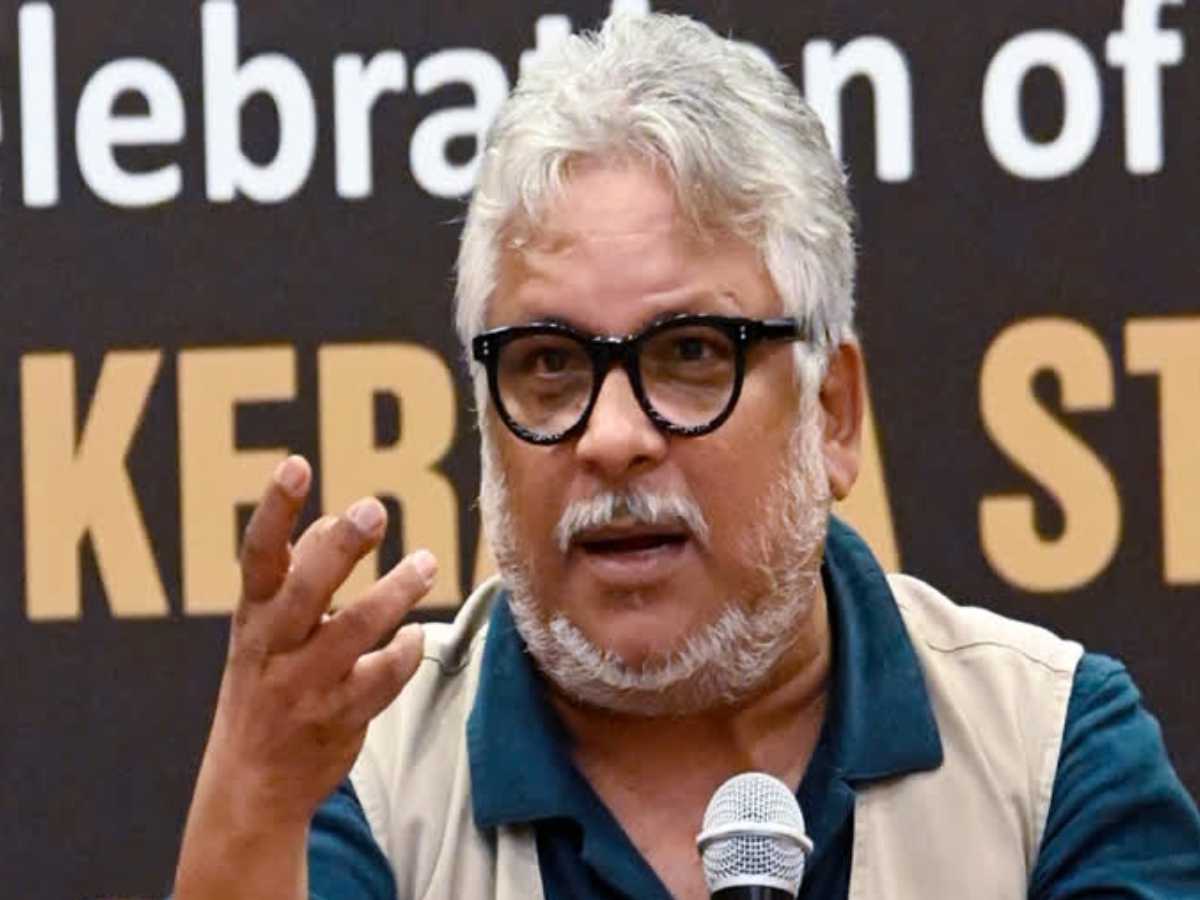

Sudipto Sen never imagined that one of his films would one day cross Rs 240 crore at the box office, spark a national conversation, and still earn him a National Award for Best Director. Yet that is exactly what happened with The Kerala Story in 2023.

“When they announced my name, I was shocked,” he recalls of the 2025 National Film Awards. “We expected recognition, maybe a technical award or even Best Film. But Best Director? That was beyond imagination. For a filmmaker, this is the dream.”

Born in Siliguri, Sen studied Physics before switching to Applied Psychology at the University of Calcutta. “Cinema wasn’t in the plan,” he admits. “I started with documentaries — small, experimental, sometimes for institutions like the World Bank. It was more of a curiosity than a career.”

His first feature, The Last Monk (2006), screened at Cannes, Rotterdam, Raindance, and Singapore. “I still remember seeing it on an international screen for the first time. For a boy from Siliguri, that was surreal. I felt cinema could take me places my degree never could.”

Finding themes in conflict

Over the years, Sen gravitated toward subjects rooted in tension and identity. “Conflict fascinates me — whether inner conflict or societal,” he says. Akhnoor (2009) won international awards, while Gurujana (2022), about Assamese saint-philosopher Srimanta Sankardeva, was selected for the Indian Panorama at IFFI.

But it was The Kerala Story that brought him both fame and fury. “People say it was controversial. But I see it as my responsibility — if a story exists in society, someone must tell it. You may agree or disagree, but cinema cannot always be comfortable.”

Between applause and criticism

The film’s staggering success surprised even him. He explains that box office figures were never his measure of success. But when audiences connected and debates started, he realised it had gone beyond cinema into the cultural space. “That was powerful, but also heavy. Suddenly, everyone had an opinion on me, not just my film.

His follow-up, Bastar: The Naxal Story (2024), turned the lens on the Maoist insurgency in Chhattisgarh. “Again, it was about difficult truths. I didn’t want to romanticise or demonise, just to ask questions through the medium of cinema.”

A taste of Delhi

Though he hails from Siliguri, Sen has developed a special connection with Delhi. “I don’t have deep roots in Delhi, coming from West Bengal, but the city has a way of drawing you in,” he says.

He often visits for film events and screenings, and over time, the capital has become a place of both inspiration and comfort. “I am in love with Delhi’s vibrant culture and enthusiastic audiences, who have always welcomed me warmly,” he adds. “And the food here — it’s a story in itself. Every visit, I make sure to enjoy it.”

Sen also appreciates the city’s thriving artistic scene. “There is a lot of passion and dedication towards theatre in Delhi. It keeps you on your toes as a filmmaker and reminds you that audiences value sincerity and craft, whether on stage or on screen.”

Also Read: Hemant Pandey: rooted in Delhi, thriving on stage and screen

The award and what it means

Receiving the National Award was a moment of vindication. “It told me the country sees value in the effort. Not everyone will like my films, but the recognition means the discourse they create matters.”

What lies ahead

Sen is not slowing down. He runs his banner, Sipping Tea Cinemas, and is developing Saharasri, a sequel to Chandni Bar, along with other projects such as Basera and Charak. “Each of them touches on social issues in some way. That’s the only cinema I know how to make.

For him, filmmaking remains an act of faith. “You never know how an audience will react — it’s like confessing love without knowing the answer. Sometimes you’re embraced, sometimes you’re rejected. But if your intention is honest, the journey itself is worth it.”

A storyteller of contested spaces

Does the criticism ever overwhelm him? “No,” he replies after a pause. “If everyone agrees with you, maybe you’re not saying anything important. Cinema is supposed to provoke, to make people think, even argue. For me, that’s success.”

From Siliguri classrooms to the red carpet of IFFI and the stage of the National Awards, Sen has carried with him a belief that cinema must engage with society’s hardest questions. Loved and criticised in equal measure, he seems content with that role: “Stories are never easy. Why should cinema be?”

Filming under tough conditions

Filming The Kerala Story presented unique challenges. Sen reveals that they had to shoot guerrilla-style in Kerala without official permissions. “In Ladakh, the cold was biting, and the winds were harsh. But we were determined to capture the authenticity of the story, no matter the obstacles.”