On a quiet stretch off Sohna Road in Gurugram, far from the urgency of honking traffic, the Heritage Transport Museum rises like a time capsule devoted to India’s evolving mobility. Spread across 100,000 square feet, the museum brings together pre-mechanised vehicles, steam-age locomotives, early aviation memorabilia, maritime artefacts and a fleet of painstakingly restored automobiles. This month, it completed twelve years — a milestone for an institution that grew out of one man’s stubborn fascination with wheels.

The museum’s founder, Tarun Thakral — hotelier, collector and tireless champion of transport heritage — greets visitors at the entrance in a cheerfully printed shirt covered in vintage cars. His lampshade moustache, reminiscent of an older era, sits under a precisely sculpted nose, signalling his affection for the past before a visitor even steps inside.

A collector’s vision

Thakral’s journey began in 1994, when he bought his first vintage car — a 1932 Chevrolet Phaeton once used by the Lahore Presidency. When he found it abandoned in the Rajasthan heat, its tyres and rubber components had melted away, leaving only the engine and the skeletal frame intact. A year-long restoration in Delhi followed. “It felt like a dead thing was brought back to life,” he recalled in a conversation with Patriot.

As his collection grew, nostalgia alone could not contain it. After approaching the government, he received a sanction of Rs 6 crore to establish a public museum under the Heritage Transportation Trust, a registered non-profit. By 2013, the museum opened its doors to the public, becoming India’s first comprehensive transport museum.

Today, Thakral owns over 100 vintage cars — 60 fully functional, and 40 currently under restoration. Sourcing spare parts often means scanning markets in the US and UK, while repairs are carried out by mechanics who understand mechanical, not electronic, systems. “If properly restored, these cars can last years,” he said. “There are still experts who repair them with love.”

Building the museum

The first surprise awaits even before visitors enter the galleries. The museum’s reception area uses benches, tables and chairs crafted entirely from discarded auto parts. Even the chai cup appears as though it may once have been a carburettor.

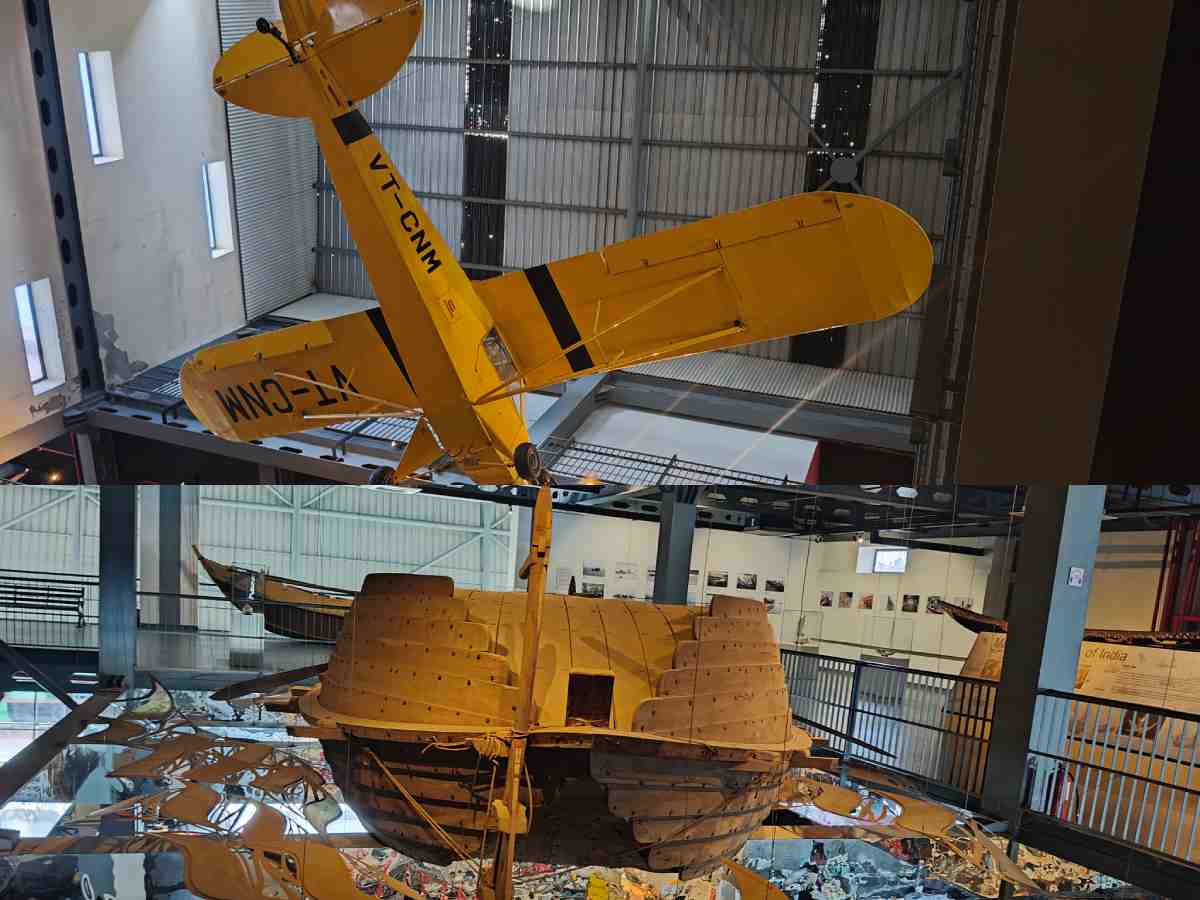

Tucked off NH-8 in Nuh district near Gurugram, the museum offers what Thakral calls “a rear view of history,” where artefacts become “the steering wheel of time.” Across four floors, more than 5,000 objects chart India’s transitions from palanquins and bullock carts to modern cars, railways, aviation and maritime mobility.

The galleries

Visitors begin in the pre-mechanised world: ornate palanquins, camel and bullock carts, and horse-drawn carriages, each set against environments recreated through murals by artist Hanif Qureshi and painted shutters sourced from across the subcontinent.

The railway gallery features a reconstructed 1930s station platform, complete with period ticket counters and signage. At its centre sits a restored Jodhpur Salon coach, purchased for Rs 5 lakh and rebuilt piece by piece.

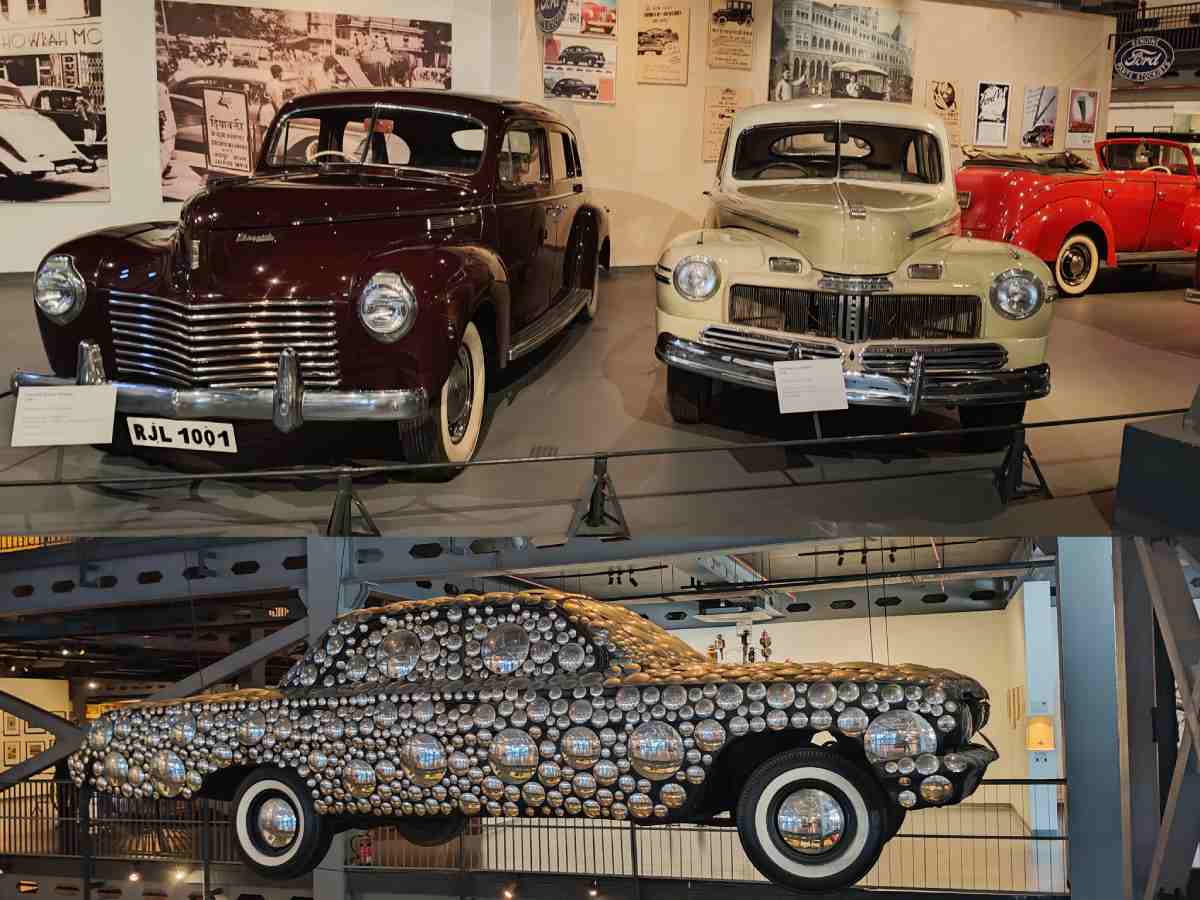

The automobile gallery is the museum’s core — about 75 vehicles including Buicks, Dodges, Fiats, Studebakers and Hindustan Ambassadors. A gleaming Mercedes-Benz S280, the same model as Princess Diana’s last car, anchors the section. Surrounding dioramas evoke old garages, spare-part shops and print adverts from a slower, less congested era.

Cinema finds its own corner too. From the Rajdoot motorcycle of Bobby to the bicycles of Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar and the iconic Sholay sidecar, the gallery traces how vehicles shaped cinematic imagination. The actual red car used in Dil To Pagal Hai sits nearby, adding a slice of Bollywood memory.

Machines and memory

The museum’s narrative quietly maps mobility onto social hierarchy. Palanquins evoke aristocratic travel, while bicycles, bullock carts and early mopeds represent working-class journeys. A section dedicated to toys — especially the beloved “dinky cars,” once imported and later manufactured in India until the market was overtaken by cheaper Chinese products — adds a layer of everyday nostalgia.

The two-wheeler floor spans the evolution from early bicycles to Lambrettas, Bajaj Chetaks, mopeds and a range of scooters that defined entire generations. Posters, songs and advertisements turn the gallery into a collage of familiar cultural cues.

Thakral admits that his fascination leans heavily towards the 20th century, though he finds it difficult to articulate why. This quiet obsession, however, shapes the museum’s soul — a tender attempt to hold close the golden decades of modern transport.

Stories of movement

The museum avoids becoming a static display. Responding to feedback from schoolchildren, it now houses interactive simulators that allow visitors to experience driving or flying early vehicles. “A museum should not lecture,” Thakral said. “It should invite.”

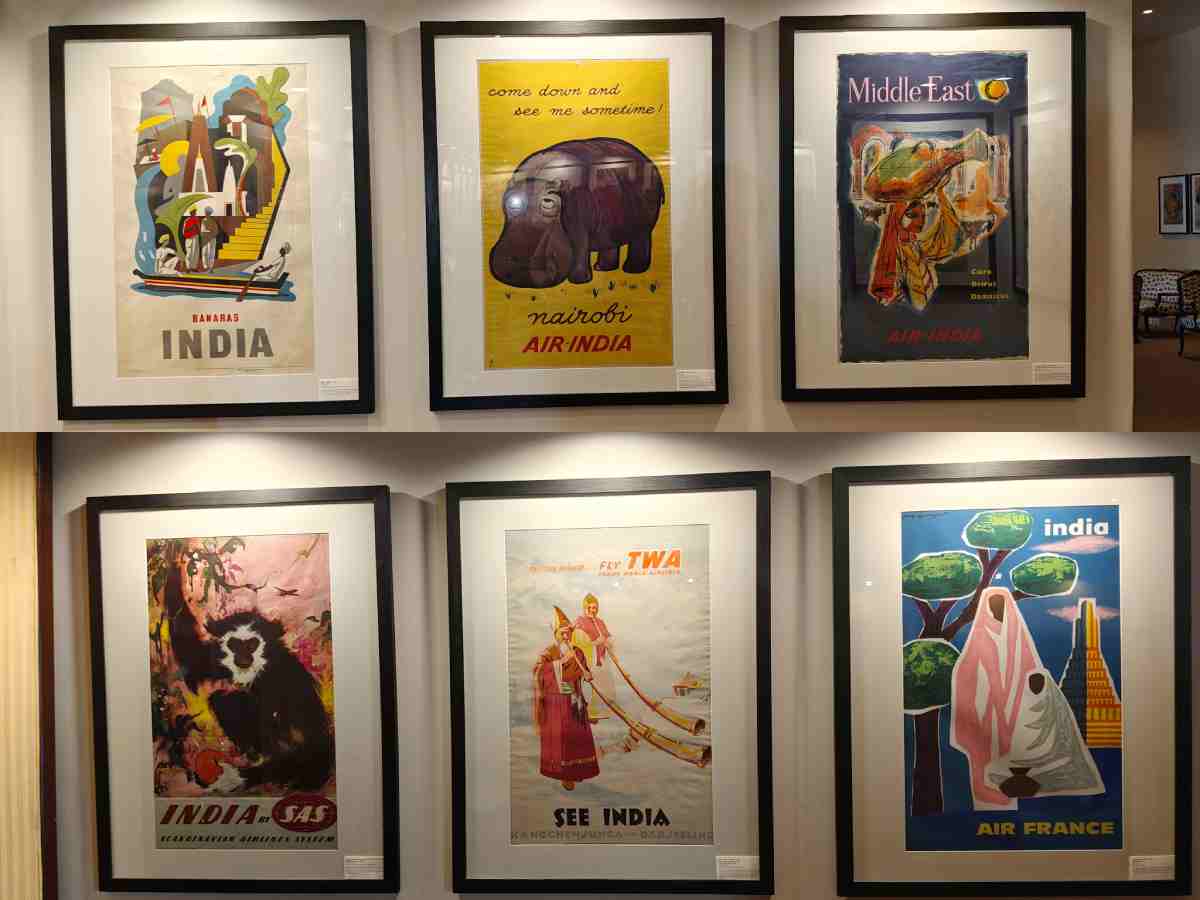

This year’s 12th anniversary exhibition, Posters That Moved India, showcases rail, maritime, tourism and aviation posters dating from the 1930s to the 1970s — rare visual documents once displayed at railway stations, airline offices and other public spaces. “These posters are time capsules,” Thakral said, offering glimpses into how India imagined travel before screens and digital design.

The museum frequently hosts themed exhibitions. Last year, Light Years Ahead explored futuristic transport concepts, while Prints of the Divine examined early Indian art that connected spirituality with the idea of journeys.

In twelve years, nearly three million people have visited the museum. For Thakral, the most rewarding moments are not always about machines. “Visitors come and take memories,” he said. “Some say, ‘I used to own that car.’ Others remember old road journeys, overheated engines, or their father stopping for water breaks. These are pieces of people’s lives.”

The museum’s immersive design — reconstructed environments, restored vehicles, and pop-cultural references — ensures that every visitor finds at least one object that connects with their personal timeline.

The museum’s immersive design — reconstructed environments, restored vehicles, and pop-cultural references — ensures that every visitor finds at least one object that connects with their personal timeline.

Preserving Heritage

For Thakral, the museum’s mission remains educational. “Heritage doesn’t belong to us unless we pass it on,” he said. “As long as we give knowledge, this heritage will survive. Otherwise, it becomes forgotten metal.”

Even as India accelerates towards electric mobility, he reserves his admiration for the modest Reva, India’s pioneering electric car of the late 1990s. “A lot of the credit for EVs in India should go to Reva,” he said, calling it an early indicator of where mobility was headed.