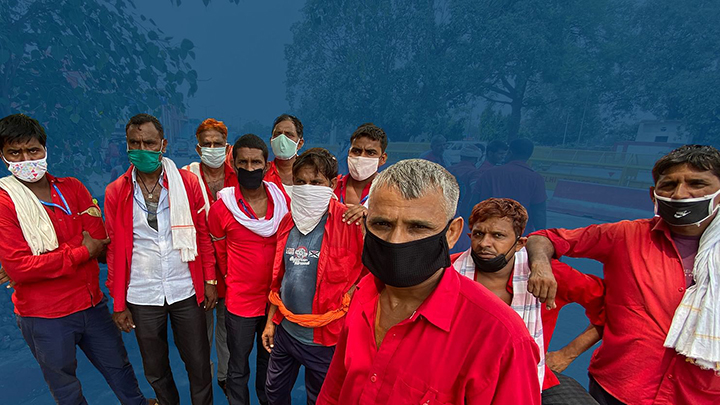

Railway porters feel crushed by the Covid crisis as fewer trains and the fear among passengers of infection means that thousands of porters have seen their incomes fall by over half

On March 20, Abdul Khan, 36, packed his bags and left for home.

Khan has been a porter at the New Delhi railway station for 25 years and his home is 330 km away, in Rajasthan’s Karauli district. But Covid had reared its ugly head, and Khan knew that tough times were ahead, so he managed to find a spot on a crowded bus and went home.

His fears were not unfounded. Two days later, the Indian Railways suspended passenger train operations, running only freight trains to transport essential commodities. This decision dealt a blow to thousands of porters like Khan across the country.

There are over 20,000 licensed porters in India. In Delhi,1,478 work at the New Delhi railway station, around 1,000 at the Old Delhi station, 97 at the Anand Vihar terminal, and between 500 and 600 at the Hazrat Nizamuddin station.

In May, the Railways operated Shramik Special trains to ferry thousands of homebound migrant workers. Special Rajdhani Express trains began on May 12 and special timetabled trains began on June 1. As a result, many porters gradually returned to work, including Khan, who came back to Delhi last month.

But it has been a struggle, especially after the government on August 11 announced that it would continue to suspend all passenger and suburban train services in view of the rising Coronavirus cases.

Khan’s income has dipped by over half compared to pre-lockdown days. Where he would earn Rs 400-500 per day earlier, he said, he now earns Rs 100-150, at the most. “I’m not able to cover my expenses without external help,” he said.

Apart from paying for food, Khan also pays Rs 5,000 per month as rent for a single room in the neighbouring Tel Mill Gali in Paharganj. During the lockdown, he said, his landlord was generous enough to waive rent for two months. But once Khan returned to Delhi, the rent resumed.

“I borrowed Rs 10,000 from my family. Going ahead, I might have to do the same,” he said. Khan’s family of nine, including four children, lives in Karauli’s Hindaun tehsil. The family relies on his income, a bigha of farmland that his father works, and a small shop run by his brother in the village.

Allah Baksh, a porter in his early 30s, told Newslaundry their incomes would be even lower if all the licensed porters had returned to work. Of the 1,250 porters actively working at the New Delhi station, he said, around half are still in their villages and hometowns.

“I used to make Rs 500-600 a day during the lockdown. Now it ranges from Rs 200 to Rs 300,” he said. This is the toughest situation he has faced in his 18 years as a porter, working from 4 am to 5 pm. To protect himself from Covid, he uses a mask and hand sanitiser.

Like Khan, Baksh went home to Rajasthan before the lockdown was announced. He returned shortly after trains began running on May 1. “But it has been more hardship than expected,” he said. “People refuse to use our services due to fear of contracting the virus. All are scared. What can we do?”

Porters told Newslaundry that they earn Rs 100, on average, to carry a load of 40 kg for up to 20 minutes. An extra Rs 100 is charged for the next 20 minutes. These rates haven’t changed since the pre-pandemic days, Baksh said, but their fortunes have. He shares a room with four other porters in Paharganj for Rs 6,000 a month. Two of his roommates haven’t returned to Delhi yet.

Baksh pointed out that their incomes are also impacted by the fact that most railway passengers right now are poor migrants. “They are in no way able to pay porterage to us,” he said. “They are financially helpless themselves.”

No assistance from the Railways

According to a June 2020 report by the India Brand Equity Foundation, 13,452 passenger trains and 9,141 freight trains ply on average every day under normal circumstances, ferrying 23 million travellers and three million tonnes of freight between 7,349 stations.

Compare these numbers to the fact that only 230 special trains are currently running across India.

Only 20-25 trains pass through the New Delhi station, porters told Newslaundry, compared to 250-300 during the pre-pandemic period. And these numbers are unlikely to change any time soon. The Shramik Special trains came to a halt on July 9. On July 14, railways minister Piyush Goyal said most trains were running at only 70-75% occupancy, some as low as 10-15% occupancy.

Much to the disappointment of the porters, the Railways has provided them no support. In April, Newslaundry was told, officials collected the porters’ bank account and Aadhaar details, so they were optimistic of receiving one-time assistance. But three months later, Khan said, “We haven’t received a single penny, nor any other benefit.”

Licensed porters pay Rs 120 to the Railways per year. In return, they get two sets of their iconic red uniforms, a complimentary travel pass, and a privilege ticket once a year for themselves and their spouse to travel in second-class or sleeper-class for a third of the standard fare. In the time of a pandemic, these entitlements mean little to the porters.

Natha Ram Meena, a representative of the Northern Railwaymen’s Union, told Newslaundry they desperately needed help. Follow-ups with Railways officials since April have elicited no response, he said. “They would not tell us anything. We are totally clueless as to why those details were collected and what the status is currently,” he said, his voice filled with frustration.

This uncertainty could be sensed when Newslaundry tried to reach Railways officials for comment. A spokesperson for the Northern Railways expressed inability to comment and asked this correspondent to speak to RP Pandey, the station director of the New Delhi station.

On his part, Pandey only said, “I am unaware of any such development. But if many of the porters have said so, I will look into it and try to furnish some information.”

As matters currently stand, the porters are left to fend for themselves. In Lucknow, a group of porters plan to approach the Supreme Court, seeking a directive to the Railways to provide them with assistance. Several porters told Newslaundry that they are considering returning to their hometowns, given that the Covid crisis is unlikely to end in the coming months.

Khan, for instance, said he can’t depend on his family for money for too long. “If my income remains this low, I will have to vacate my room and leave in a month or two,” he said. “I have stopped expecting help from the Railways or the government. We work so hard to carry others’ loads, but nobody cares about our plight.”

www.newslaundry.com