The secret of longevity, as is evident when profiling nonagenarians, is their resilience and optimism, a sacrosanct routine, their enviable ability to love life

One thing is for sure, they didn’t plan to live that long — just ended up being nonagenarians. These citizens of Delhi, well into their nineties, are still leading a fairly healthy life at a truncated pace, in their own quintessential way. Their secret formula? Slow and steady wins the race. Their days are spent productively, they have a set routine and they eat healthy in small quantities.

It’s not easy, for in this long journey they lost many of their dear and near ones, some even their children, and as very few of their own generation have survived, they feel lonely out there in the evening of their life. Having said that, there are striking similarities, their enviable ability to love life however adverse the circumstances may get, their resilience and optimism. In a way, immune beyond a point to the ups and down in life. Age didn’t catch up with them for they managed their day-to-day life well — they are particular about an active routine, certain activities are sacrosanct every day.

All this is not to suggest that any of their lives was a fair weather experience. Longevity is also seen to persist in most awkward circumstances. For instance in June this year, a 93-year-old man, Rohtas from Baghpat district in the National Capital Region, petitioned the apex court challenging the life sentence that was awarded to him 40 years ago. Rohtas’ plea is that it was an act of self-defence as he was part of a scuffle between two parties over harvesting crop from a piece of land in which some people were injured, one of them died. He has lived for last four decades in jail under testing conditions, with only his quest to secure justice keeping him going.

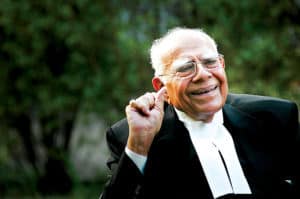

While Rohtas could be a victim of India’s slow criminal-justice system, a major beneficiary is Ram Jethmalani, the highest paid criminal lawyer of the country. Perhaps, he’s the seniormost lawyer of the country as last month he entered the 96th year of his life. The incumbent Supreme Court judges weren’t even born when he started practice some 75 years ago. He lives in a mansion in Delhi, and now hardly ventures out of his bastion. Till about five months ago, he was regularly playing badminton. Lately, because of indifferent health, he’s taking it easy.

But make no mistake, he still leading a fairly active life. Wakes up at 7, walks on a treadmill, gets ready, takes his breakfast, and is in his office latest by 10:30 am. He reads newspapers and periodicals, receives visitors, gives legal advice, though he has given up active practice. This goes on till about 1 pm. He doesn’t take lunch but takes a nap, is back in office for a couple of hours after having tea at 4 pm. He goes for a stroll as the sun sets. His evening is spent with family and friends who come calling on him. He, unlike the famous journalist and writer Khushwant Singh who died at the age of 99, is not a scotch drinker.

His poison is cognac-brandy served in lukewarm water: two pegs, not more, not less.

Shyam Rani Kaul is a year older than Ram Jethmalani. She’s skinny, but her skin still glows. She grew up in Srinagar, married when she was only 13 years of age, before independence. Her husband Gopi Nath Kaul was a PhD and an academician. She lives with her surviving children, either in Delhi’s Green Park or in Baroda. A stickler for routine, she wakes up at 3:30-4 in the morning before dawn, cleans her little in-house temple, takes a bath, and performs her morning prayers. “She does everything on her own, but over the years, she has slowed down,” says Dr Nidhi Tikku Mitra, Phd in Psychology, her granddaughter or, to be more precise, eldest daughter of her eldest daughter.

Shyam Rani Kaul always led a disciplined life, eats little, only as much as her body demands. Now at the age of 97, she’s even more careful about what she eats as her digestion is weak. Usually her meal consists of a roti soaked in milk or tea, a select vegetable, boiled with no spices. Sometimes, when a delicacy is cooked in the house, she takes a bite or two, but never indulges herself. She takes care of all her personal needs, and is particular about how she takes her medicine. After taking a pill, she waits for 5-10 minutes before she swallows the next pill. It’s a bit of a ritual.

A grandmother of 11 adults and great grandmother of 6, Shyam Rani tells her family, “I live for you all.” She likes watching television and loves chatting. She’s very happy attending weddings and family functions. In the last 20 years, she lost her husband and two daughters. A year ago, she lost a son-in-law whom she loved like her own child. Her grand-daughter Dr Nidhi Tikku Mitra narrates her ordeal: “It’s tough, very tough for her. She’s emotionally stressed and says ‘My children are gone and I’m here.” Loneliness can be traumatic. “You have to live for us,” Dr Nidhi keeps reassuring her.

There are some who have a fixated point of view and their own strategy to deal with life. They express a contrarian view to assert themselves. This is the case with a 93-year-old army veteran, father, grandfather and great-grandfather of 20 people, who’s critical, interested and reactive about things that happen around him.

“I’m a private person and hate attention. Don’t identify me in your article,” he’s categorical and rather dismissive. “There’s nothing extraordinary about the fact that I have lived so long. This is not an achievement,” he says with a shrug after his grandson persuades him to talk.

A slender man of average height, his face looks younger than his body, frail behind his loose clothes. He walks ramrod straight when he goes for his morning stroll. After his walk, he sits on a bench for about an hour or so, watching children play while thinking loudly. He lives with the eldest son of his youngest son in a house in South Delhi that he built in the 1960s. All his children are dead, his youngest son having died a year ago.

Lately, he has become religious for the first time in his life, reads mythological texts every morning. But that hasn’t interfered with his daily ritual of drinking a peg or two of rum in the evening. The nonagenarian narrates the story of film actor Ashok Kumar who claimed that he’d live for 100 years. “He didn’t, I might. But that’s not an objective, just a feeling. I know every day is a bonus. But as long as I live, I will live on my terms,” he says as if he’s made a promise unto self. Then quotes Mark Twain, “Age is an issue of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it doesn’t matter.” He finally smiles.

Vimla Tiwari is a poet with the pen name “Vibhor”, which means indulgent with life — which she is. Married to a banker Naresh Chandra Tiwari, she had to face the wrath of a strict mother-in-law. But that’s all in the distant past. Now she lives with one of her sons Sanjay Tiwari, an entrepreneur, an amateur photographer and a globetrotter in Vasant Kunj. She’s an integral part of various activities that take place in the household. Seated on a big white leather couch that looks like a throne, in front of a giant television, she actively participates in parties and gathering, where her son, grandson and granddaughter and their friends, drink, eat and make merry.

She’s well informed and likes to indulge in intelligent conversation, and enthralls people with her ready wit, humour and candidness; sensitive, interested and open to new ideas.

She’s young at heart and hard of hearing. Despite that, she spends a lot of time watching television. It’s like watching a silent movie with colour, fun and frolic. While watching animated visuals on television, she is constantly imagining her own set of dialogues, giving voice to the dumb characters in her mind — as if lip reading.

So when she was taken to a doctor to deal with her hearing impairment, she told her son Sanjay in the middle of the treatment, “I want to go back home. It is my problem. Why are you deciding what I should do about my problem?” Sanjay had to summon another doctor, a friend, to convince her to get the treatment done. She relented but hardly ever wears the hearing aid. “I make myself heard. I don’t have to hear all noises around me,” she tells her son.

As is evident, she never loses an argument — at worst, there’s a stalemate. When the difference of opinion remains unresolved, she writes a poem. She’s interested in everything that happens around her, yet attends to her daily routine meticulously.

Doesn’t let others hinder her routine, doesn’t hinders others’ life. Her skin glows, she has a pleasing personality, never seems to be judging people, but is a keen observer.

And despite her age, most of her hair is still black. One day, while combing a streak of grey hair over her earlobe, she says as if it has just struck her: “Thore baal safed ho gaya hai. Mai buddhi ho rahi hu (Some of my hair is white. I’m getting old.)”