In her flat in East Delhi’s IP Extension, Meera Bhardwaj closely follows every update on the upcoming Delhi Assembly elections. A veteran of the political stage, Bhardwaj rose to prominence during the 1998 elections, when she secured a decisive victory as the Congress candidate from the Patparganj constituency. Her triumph was extraordinary—not just for its margin, but for the barriers it broke as she, a Malayali by birth, carved a place in a political landscape dominated by Hindi-speaking leaders. Married to PK Bhardwaj, a respected journalist, Meera’s victory stood as a testament to the inclusivity that Delhi politics briefly embraced.

Scanning the results of Delhi’s first Assembly elections in 1952 reveals another notable exception: Prafulla Ranjan Chakravarty, who won from the Reading Road (now part of the New Delhi constituency) seat on a Congress ticket. “Reading Road was a bastion of the Bengali population in Delhi during those days,” recalls veteran Congress activist Pritam Dhariwal. “They were mostly central government employees living in the Gole Market area and supported fellow Bengali Chakravarty.”

However, aside from these rare examples, Delhi’s political narrative has largely excluded candidates from linguistic minorities such as Tamils, Malayalis, and Bengalis. Even today, the trend remains unchanged. The ruling Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has announced its candidates for all 70 Assembly seats, yet not a single nominee hails from a non-Hindi-speaking background. The Congress, which historically gave tickets to leaders like Bhardwaj and Chakravarty, has also ignored linguistic minorities in its candidate list. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) follows a similar pattern, focusing primarily on candidates with roots in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, and Bihar.

A legacy of linguistic diversity

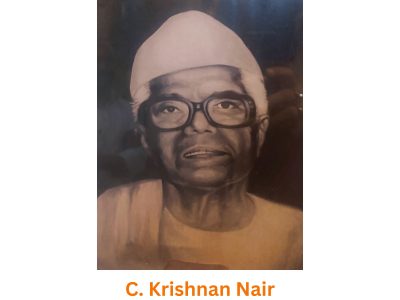

In the past, Delhi appeared more open to leaders from non-Hindi-speaking states. CK Nair, a Malayali, was elected to the Outer Delhi Lok Sabha seat in both 1952 and 1957. Known as the “Gandhi of rural Delhi,” Nair played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). “CK Nair was a remarkable gentleman,” says noted author and journalist AJ Phillip. “He participated in Gandhi ji’s Dandi March and was even considered for the position of Delhi’s first Chief Minister in 1952.”

Another significant example was CM Stephen, a senior Kerala leader fielded by the Congress in the 1980 Lok Sabha elections from the New Delhi constituency. Despite addressing rallies in Malayalam, Stephen gave BJP stalwart Atal Bihari Vajpayee a tough fight, losing by a narrow margin. Similarly, Gujarati leader Shanti Desai rose to prominence in Delhi during the 1970s and 1980s, serving as a top BJP leader in the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) and even as Mayor. Mukul Banerjee, another notable figure, was elected from the New Delhi Assembly seat in 1971. Yet, such instances remain few and far between.

Exclusion in modern politics

Today, Delhi’s linguistic minorities find themselves largely sidelined. Venkat Sundram, a Tamilian who captained Delhi University’s cricket team and headed the BCCI Pitch Committee, voices his frustration: “My father, PV Sundram, was one of the founders of the Delhi Tamil Education Association (DTEA). Despite decades of contributions, people like us are only expected to support political parties without being given the opportunity to represent them.”

The exclusion extends to local governance as well. Analysing the results of the last MCD elections reveals that all 270 winners were either from Delhi or had ties to Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Punjab, or Haryana. The linguistic diversity that defines Delhi as a “mini-India” is conspicuously absent in its political representation.

Lessons from Mumbai

Delhi’s political stagnation contrasts sharply with Mumbai, where non-Marathi-speaking communities consistently secure representation in municipal, assembly, and parliamentary elections. Sunil Negi, an author and political activist, remarks, “Delhi had an opportunity to brighten its image in the upcoming elections by embracing political diversity. Unfortunately, it has chosen to remain status quoist, unlike Mumbai, which sets an example of inclusivity.”

Contributions beyond politics

The contributions of Delhi’s linguistic minorities extend far beyond the political arena. Communities from Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Bengal, and Maharashtra have established schools like the DTEA, Kerala School, Raisina Bengali School, and Nutan Marathi School, shaping generations of Delhi’s youth. In business, Tamilian entrepreneur Shiv Nadar has redefined success. Originally from Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur district, Nadar began his career at DCM Data Products before founding HCL Enterprises in a Patel Nagar garage in 1976. Today, HCL is a global technology giant, with 80% of its revenue derived from international markets. “Shiv Nadar had a deprived childhood but struggled to secure an education,” says Tamil and Hindi poet Bhaskar Rammurthy. “He now invests heavily in schools and educational institutions, giving back to Delhi more than he has taken from it.”

A call for change

Despite these contributions, Delhi’s political landscape remains exclusive. The BJP, Congress, and AAP have all failed to field a single candidate from a non-Hindi-speaking background for the upcoming Assembly elections. As Negi points out, “Delhi had a unique opportunity to elect municipal councillors and MLAs from communities like Bengalis, Tamils, and Gujaratis who have enriched this metropolis for decades. Instead, it has chosen to overlook them.”

Also Read: Delhi’s first assembly election: A journey back to 1952

Delhi and Mumbai’s rivalry may be legendary, but when it comes to political diversity, Mumbai emerges as the clear winner. The national capital must take cues from its financial counterpart and embrace the inclusivity that defines India’s democratic ethos.