Once thought to be under control, tuberculosis (TB) has made a worrying comeback in the national capital. According to the Annual Report on Registration of Births and Deaths in Delhi 2024, 4.86% of all recorded deaths in the city last year were caused by TB — up from 3% in 2020. This sharp rise, nearly doubled in just four years, reflects a resurgence of an old epidemic driven by drug resistance, overcrowding, poor treatment adherence, and systemic gaps in healthcare and awareness.

A sign of systemic neglect

Public health experts warn that Delhi is now paying the price for years of complacency. “The rise in TB deaths is alarming and signals a breakdown in treatment continuity,” said Dr Rajesh Kumar Grover, former Director and CEO of Delhi State Cancer Institute. “Drug resistance, incomplete treatment, and co-morbidities such as diabetes, malnutrition and chronic respiratory disease are combining to make TB more lethal and difficult to manage.”

According to Dr Grover, the disruption of healthcare services during the pandemic also contributed to the surge. “During COVID-19, TB patients could not reach DOTS centres for their regular medication. Many defaulted on treatment or missed follow-ups, and those interruptions led to an explosion of multi-drug-resistant TB cases. Now, we are seeing the after-effects — resistant strains that are spreading faster and proving harder to cure,” he said.

Also Read: Delhi government targets 13 pollution hotspots with action plan

Overcrowding, poor hygiene, and ignorance driving infections

Adding to the concern, Dr Kuldeep Kumar Grover, Head of Critical Care and Pulmonology at CK Birla Hospital, Gurugram, said that social and environmental factors have worsened the crisis. “The rise is mostly related to overcrowding, poor compliance to medicines, and unhygienic living conditions. In congested, unclean, and impoverished areas, awareness is extremely low,” he explained.

He noted that even though the government provides free and supervised treatment under the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme, non-adherence remains a major hurdle. “Despite having supervised treatment, door-to-door drug distribution, and thousands of health (Directly Observed Treatment) DOT centres, patients often stop taking medicines midway. Many tell us they took the treatment for two weeks and then stopped because they felt better — but that is exactly how resistance develops,” he said.

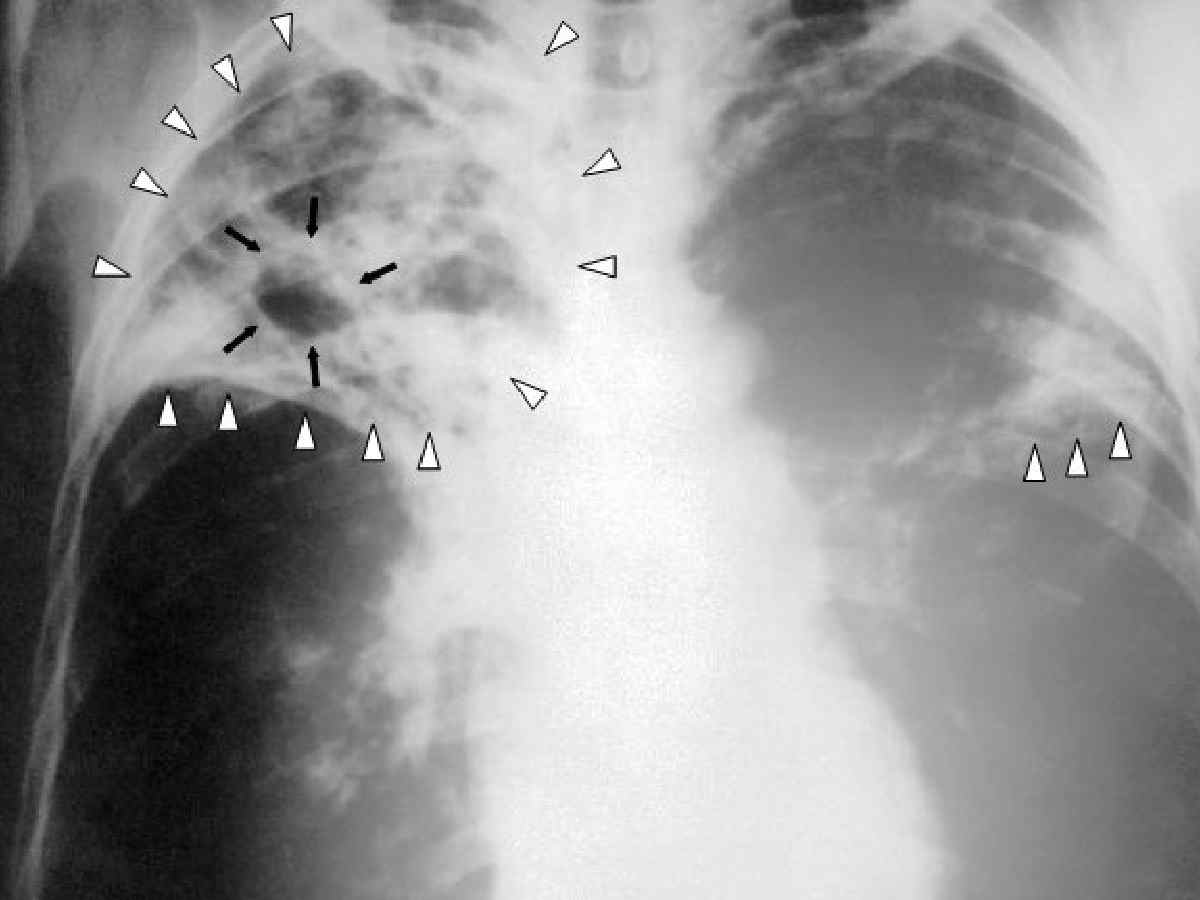

“Tuberculosis is a notifiable disease, yet for years it was being treated casually — even by people without adequate medical knowledge,” he added. “Some patients received treatment for two or three months instead of the full course of six months, leading to the rise of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) and total drug-resistant (TDR) TB. Today, we are seeing a bulk of patients with severe, complicated cases — presenting with symptoms like coughing with blood and fluid in the chest. These patients are extremely hard to cure because they were never compliant with earlier treatment.”

Dr Kuldeep also pointed out that ignorance, fear, and poor nutrition play a major role in worsening outcomes. “Many TB patients believe they can’t continue medicines if their diet is poor, or they stop treatment thinking it’s no longer needed. TB is easily curable if treatment is completed, but without full adherence, it becomes a life-threatening problem,” he said.

Drug resistance and systemic gaps

The rise of drug-resistant TB has turned the disease into a formidable public health challenge. “MDR-TB is now one of the most serious challenges in Delhi,” said Dr Rajesh Kumar Grover. “Incomplete or irregular medication allows the bacteria to adapt, and once resistance sets in, treatment becomes 10 times more complicated. Many patients require prolonged and more toxic drug regimens, and mortality rates are higher.”

He added that fragmented healthcare systems are worsening the problem. “A large proportion of TB patients initially seek treatment in the private sector, where reporting and follow-up are inconsistent. Some clinics do not follow the national TB protocol, leading to underreporting and incomplete courses. Without full coordination between public and private providers, we cannot track or support all patients effectively.”

Experts point out that nutrition and living conditions remain overlooked. “TB is a disease of poverty,” Dr Grover said. “Malnutrition weakens immunity, overcrowding facilitates spread, and air pollution worsens respiratory vulnerability. Migrant workers, slum dwellers, and low-income groups are most at risk. Unless we improve their living standards, food security, and sanitation, TB will continue to thrive.”

The way forward: strengthen screening, compliance, and awareness

Both experts agree that controlling TB in Delhi requires urgent, multi-dimensional action — combining medical, social, and technological interventions.

Dr Kuldeep emphasised the need for intensive, slum-focused screening campaigns. “We need targeted screening drives in congested areas using handheld X-ray technology and AI-based tools to detect cases early. Mobile diagnostic vans and rapid molecular tests like CB-NAAT and TrueNat must be deployed widely to identify infection before it spreads,” he said.

He added that community engagement and integrated care are essential. “TB cannot be fought in isolation from the people it affects. We must educate families, strengthen community counselling, and ensure every patient receives nutritional support and proper follow-up. Technology can help us track adherence, but compassion and outreach are just as vital.”

Dr Rajesh echoed this view, urging stronger enforcement of drug-resistance testing for all new TB patients and the use of digital tools for treatment adherence. “Mobile-based reminders, teleconsultations, and home visits by trained health workers should be part of the strategy,” he said.

He also called for a unified public-private data system through the government’s Ni-Kshay portal. “Every clinic, hospital, and diagnostic lab must report TB cases in real time. Without accurate data, the government cannot identify hotspots or monitor treatment outcomes effectively.”

Public education, the experts agreed, is the missing link. “We need to speak about TB with the same urgency we had for COVID-19,” Dr Rajesh Grover said. “People must know that TB is curable, free treatment is available, and early diagnosis saves lives. But stigma, ignorance, and fear are holding us back.”

Dr Kuldeep added that improving dietary support and nutritional counselling must become part of the government’s strategy. “If patients are well-fed and educated about the disease, compliance improves dramatically. TB medicines work best when the body is nourished and strong,” he said.

Also Read: Delhi’s missing children: trafficking, neglect and poverty fuel a deepening crisis

Ultimately, both doctors agreed that tackling TB in Delhi requires sustained political will, public awareness, and accountability in the health system. “The government’s TB programme is well-structured,” Dr Kuldeep said. “But it will only succeed when people follow through, when communities participate, and when healthcare systems reach those who need them most.”

Dr Rajesh summed it up bluntly: “Tuberculosis is both preventable and curable. But without consistent treatment, responsible reporting, and better living conditions, Delhi will continue to pay a heavy price. TB is not just a disease — it’s a mirror reflecting the gaps in our public health priorities.”