Fuelling chaos and panic, misinformation makes its way insidiously through our phones amid the global pandemic

Last year, public health related misinformation garnered 3.8 billion views on Facebook, according to a US-based NGO Avaaz. And amid the global pandemic, viewing of misinformation peaked in April this year.

Avaaz claims that misinformation-based content on top 10 such websites are getting four times higher views on Facebook than the more authentic content on the websites of 10 leading health institutions, such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This is happening even after several measures have been taken by Facebook to control the dissemination of misinformation. Not just Facebook, other social media sites like Twitter, WhatsApp, YouTube have become reservoirs of fake news, sketchy theories about cure, origin, causes and many other things.

WhatsApp has put limitations on forwards and Twitter also started putting labels and warnings on Covid-related conversations. Google has also worked on its algorithm — now a search about Covid doesn’t take you to unauthenticated news sources, and on YouTube too any such videos do not pop up on a search.

Despite all these efforts, misinformation is making its way to these social sites and exacerbating the public health crisis.

During the fight against Covid pandemic, one of the biggest challenges that the world faced was what has been dubbed as “infodemic”. WHO defines it as “an overabundance of information and the rapid spread of misleading or fabricated news, images, and videos.”WHO Director General Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at the beginning of the Covid-19 outbreak in February, “We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic”.

The question that arises now is why and how the infodemic became that big a challenge all of a sudden. Kasisomayajula Viswanath, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Health Communication at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, who was quoted in an article for the Harvard Gazette has an answer to this question, “the popularity and ubiquity of the various platforms means the public is no longer merely passively consuming inaccuracies and falsehoods. It’s disseminating and even creating them, which is a “very different” dynamic than what took place during prior pandemics MERS and H1N1.”

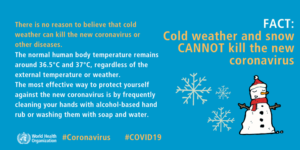

Misinformation outbreaks can eclipse the accurate and evidence- based public health guidelines from authentic sources, as anxious people would rush to try sketchy remedies and believe false theories, putting themselves and many others at risk.

A research paper published in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, identified 2,311 reports of rumours, stigma, and conspiracy theories in 25 languages from 87 countries. It found that in these reports, “Claims were related to illness, transmission and mortality (24%), control measures (21%), treatment and cure (19%), cause of disease including the origin (15%), violence (1%), and miscellaneous (20%). Of the 2,276 reports for which text ratings were available, 1,856 claims were false (82%).”

Paper identified three waves of “infodemic”. “The first wave was between January 21 and February 13, the second wave was between February 14 and March 7, and the third wave was between March 8 and March 31, 2020.” Paper also says that the misinformation about health fueled by rumours, stigma, and random theories can have serious health implications.

Rumours about alcohol disinfecting the body made people who believed in these rumours drank methanol. “This resulted in 800 deaths and 5,876 hospitalisations, and 60 cases of complete blindness.”

In April, a man was moved by a video on social media about the cure of Coronavirus by a drink made from toxic seed Datura (ummetta plant in local parlance). He encouraged neighbourhood families to do this as well, which caused 12 people including five children, to fall sick after consuming that drink.

Another man in West Bengal fell ill after consuming cow urine on the advice of a BJP leader, who organised an event vouching for cow urine as a cure for Covid. Not just that, several people died by consuming hand sanitisers during Covid lockdown, when alcohol was unavailable and false theories about the process to make alcohol (drink) from sanitisers were peddled.

Misinformation and rumours have also led to violence. Since March, several incidents of racial attack on Northeast Indians took place on the false pretext of their being carriers of viruses. Healthcare professionals were attacked in various parts of the country.

On 17 August, a self-described doctor with no formal medical training Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury uploaded a video on Twitter of an “anti-mask” group. In the video, one of the group members said while pointing to their mask “This is not independence.” Another said, “It’s a psychological operation to control you.” Towards the end of the video they burn their masks. This video reportedly garnered over 6 lakh views before being taken down.

Choudhury has on multiple occasions peddled misinformation on social media. He has been even invited by various news channels to share his views. His old YouTube channel, which was taken down, reportedly had more than 32 million views. Since he has a lot of following, his claims can have potentially dangerous implications.

He is not alone, many self-described doctors peddled lies and rumours by misquoting healthcare guidelines. Religious leaders and astrologers made the case worse.

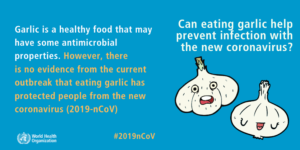

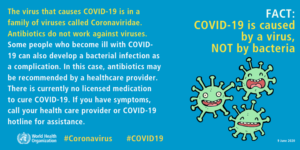

Claims were also made that Covid is not a viral disease but a bacterial infection, that eating Chinese food and even non-veg food can cause its spread. Then there was misleading advice about eating garlic, keeping the throat moist, taking Vitamin C and D as ways to stop the infection.

Misinformation was shared from not only inauthentic, unverified sources but also seemingly authentic sources. When Covid-19 had not yet been declared a public health emergency, around January end, AYUSH ministry shared an advisory via PIB suggesting Arsenicum album 30 as a ‘prophylactic medicine’ (prophylactic drugs are given to prevent certain disease) to prevent Coronavirus, which was not scientifically proven.

Dr. Sumaiya Shaikh, founding editor of Alt News science, wrote in an article on the subject, “Arsenicum album 30 has not been proven or researched scientifically by homeopaths to cure Coronavirus or any other infections in humans.” The Gujarat government, to everyone’s surprise, distributed Arsenicum album 30 to half of its population in the last five months.

Pratik Sinha, co-founder Alt News says, “Unlike US where Covid is an election issue and various theories are being peddled disproving Covid itself, in India the majority of misinformation was circulated around cure, prophylactic care and detection. For instance, a video of Baba Ramdev was run by tv channels like India Today where he says, “If you are unable to stop your breath for a minute that means you are Covid positive”. This was an example of misinformation about detection, which was shared widely. Also, medicines like Coronil were promoted as a cure for Covid by Patanjali till the government stepped in.

Rajneil Kamath, founder of a fact-checker website newschecker.in believes that there were three major waves of Covid misinformation in India. “Initially, when the first story started to emerge from China about its origin. People were curious about the disease and how it spreads. So a lot of misinformation was around this. Then it moved on to the first case that was detected in India. The curiosity increased, so did the misinformation.”

“We noticed the third wave when the Prime Minister announced lockdown in March. Then last during the Tablighi Jamaat incident,” he added.

Misinformation and the rat race didn’t even spare reputed medical journals like Lancet. In June, Lancet had to retract a study and apologised for publishing it after several scientists raised the alarm over data used in this study. The study raised safety issues with the use of hydroxychloroquine. Another reputed medical journal New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) also retracted a paper published by the same company on similar grounds. This raised several issues around scientific research during a pandemic.

It is not happening for the first time that misinformation around the public health crisis is being shared widely. In 2014, the Ebola communication crisis fueled by misinformation around it generated fear and also enmity. The 1918 Spanish flu was termed ‘Spanish flu’ even without any verified proof about its origin. Many sceptics still argue that HIV does not cause AIDS and the measles vaccine causes autism. These conjectural arguments persist despite several scientific claims and evidence proving them wrong.

Therefore, international agencies were well aware of this crisis. Various countries including India are forming alliances to counter misinformation. Spiralling demand for fact checking gave rise to an increasing number of fact-checking organisations. As per Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, English-language fact check organisations rose more than 900% from January to March.

Some fact checking websites that we contacted told us that their work has increased since Covid outbreak. Kamath says that they have doubled the number of fact checks they used to do before Covid-19.

A quick response to misinformation can reduce its impact, Adam Kucharsky in his book Rules of Contagion writes, “According to Tokyo-based researchers, a quicker response could have been even more successful. Using mathematical models, they estimated that if the correction had been issued just two hours earlier, the rumour outbreak would have been 25 percent smaller.”

When proper cure is unavailable, rumours and misinformation are common. In the world that we live in, where humans are dealing with a lot of information on a daily basis, the infodemic is increasing the intensity of the crisis as people with vested interests are cashing in, hate politics expanding its space and the disadvantaged are suffering more.