Saloni*, a social sector professional, has been working from home for more than two months. It has not been a happy time, as she expected it to be. She is staying at her sister Preeti’s home, helps her in cooking and other chores while simultaneously managing her work.

She loves her sister, and admires her as well — but after marriage, Saloni noticed a change in her. Preeti seems more like their mother now – very much absorbed in familial ties, and has no interest in politics. Whereas, Saloni has strong views on the government’s handling of Covid-19, Shaheen Bagh, Delhi riots and more such issues.

In this household, she often enters into arguments about politics with her brother-in-law, but Preeti only listens passively. Moreover, before marriage she was working as a school teacher. Afterwards, Preeti gave up her career to devote herself to her husband and kids.

Saloni reminisces about her younger days, particular spaces in her home, her Bhumihar (landowning) family. She says there was an unstated division, in their house, between what men can do and what women can do.

The angan (courtyard) was a space where women and maids often spent their day while men occupied the hall, where most socialising used to happen. “Women rarely went to the hall. When there was a gathering, we used to go to collect empty tea-cups,” she says.

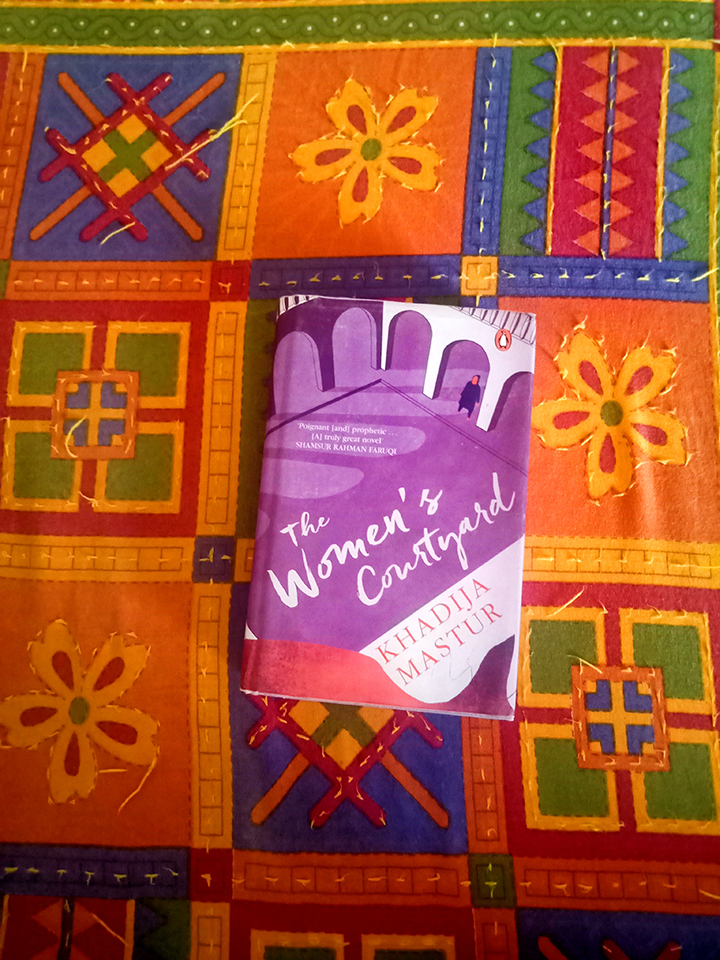

Salon’s life story is a reminder of Khadija Mastur’s Urdu novel Angan, which was published in 1962 and later translated twice – first by Neelam Hussain in 2001 as Inner Courtyard and in 2018 by Daisy Rockwell as Women’s Courtyard.

Angan is a poignant tale of the shattering denouement of Partition, that captures the less talked about enclosed space surrounded by rooms of the house and open to the sky.

Since we all are living in a pandemic world, though quite different from the Partition era, this novel is very relevant in revealing the impact of the crisis on women and relevance of spaces in a house.

This is a time when most of the family members are staying put throughout the day, thereby putting a heavier load on women members. In the absence of house help, women are spending extra time cooking, cleaning and caring for others in this crisis. Indian women generally spend up to 353 minutes a day on household work while men spend up to 53 minutes only.

A lot of women therefore live a claustrophobic life in a family trapped inside the four walls of a house. Ironically, this is considered a ‘safe space’ for women, instead of a constraint on her freedom.

An important element in the novel was sexual violence in the family, which Mastur may or may not have intentionally touched upon as a subject. When Aliya’s cousin Jameel forcefully kissed her, she couldn’t do anything at that time — but that episode gave her the strength to crush her hidden affection for Jameel. She learnt to focus more on her studies and work.

The National Commission for Women says there has been a two-fold increase in gender-based violence across the country since March, 2020. When most of the cases go unreported and the perpetrator often is a family member — the situation looks grim. It serves as a reminder that a crisis situation affects women more than men.

As seen in the book, the working man occupies a rather political space which is the hall in a house, where a lot of political discussions happen. The other rooms are generally spaces for eating, worshipping and discussing family matters.

The protagonist of the novel, Aliya, lives in fear of having to lead such a claustrophobic existence. She regards love and marriage as traps that lead to subjugation of women but has a sympathetic view about those who are part of this system. Mastur brilliantly limits the narrative of the story to the household’s spaces for females, depicting with piercing feminist gaze the impact of political lives of males on the household. These men have less interest in family issues, they are more inclined toward politics of the time.

The most remarkable part of this tale was that Mastur, unlike her contemporaries Bhisham Sahni, Yashpal, Ismat Chughtai and even Manto, contemplated the impact of Partition on a family with a seemingly personalised narrative which is highly political too. When Chammi, Aliya’s cousin, shows outright support for the Muslim League just to irritate her uncle who is Congress supporter, the entire family is antagonised.

Partition politics directly affected men in the family, but women’s lives did not remain untouched. Decision of Aliya and her mother to migrate to Pakistan were deeply ingrained in the Zeitgeist of partition.

Mastur does not write about the patriarchy of man alone. She also sheds light on the deep-seated patriarchy of the women characters. She depicted the brutal behaviour of Aliya’s mother and grandmother toward those who dared cross boundaries of culture and their beliefs.

Male characters of her story are complicit., they don’t take responsibility for the wellbeing of the family. For them, politics of the outside world is more engrossing. The somewhat apathetic behaviour toward Asrar Miyan, low-born cousin of Aliya’s father, is an important ironic factor of family life.

Saloni is very different from Aliya, who fails to find love in her life — because Saloni has someone whom she loves. However, both are wary of the changes associated with marriage.

In the last chapter of the novel, Aliya meets her cousin Safdar, who proposes marriage. She first agrees, then demurs because Safdar had given up his ambitions and his political stand and decided to do business. Aliya never wants a husband who will give her a big house and car, but not dream of a better polity. One can argue now that she then wanted a man like her father (a person who gave primacy to his political beliefs over family). Well, that’s a matter of interpretation so integral to good literature.

Mastur captures the predicament of women in a time of crisis, which is different from horrors like rape and violence that her other contemporaries exposed. Amid the grim reality of Covid-19 and its life-threatening presence, such perspectives are often ignored.

(*Names have been changed to protect identity)

(Cover: Unlike her contemporaries, Khadija contemplated the impact of Partition on a family with a seemingly personalised and highly political narrative // Photo: Mayank)

Youth shot dead by bike-borne attackers while returning from marriage function; police recover cartridges, begin…

Arunachal women allege racial slurs and humiliation by neighbours over repair work dispute; police register…

The magistrate said the probe reveals that multiple associates could be absconding, which could tamper…

The cylinder blast injured six police and fire personnel deployed at the house where a…

Multiple operational teams have been deployed to probe the case. Crime and Forensic Science Laboratory…

The initiative focused on a victim-centric approach and aimed at strengthening public trust through proactive…