Michiel Baas’s book that looks at the social settings and aspirational trajectories of India’s new middle class is an important contribution to the understanding of urban centers in the country

“Little things” was how VS Naipaul began his response to a journalist’s question on how he could foresee in the late Eighties that India was on the cusp of a major change in its economic and social trajectories.

While talking about his 1990 travelogue India: A Million Mutinies Now, Naipaul foresaw some clear signs of restless change, including a stronger urge for upward mobility, coming soon even in the years preceding economic liberalisation. He observed, for instance, that children of domestic workers in different households were getting educated.

Almost three decades after a set of changes brought along with the 1991 economic liberalisation, Naipaul’s “little things” could be seen in the different forms these changes took in urban India. The already multi-layered middle class saw millions of new entrants, now called the new middle class.

How does this new entity interact with the idea of middle-classness in India? What challenges and anxieties are navigated by this new middle class, in its dealings with other occupants of the middle-, upper middle-, mid middle- and even lower classes? In its effort to climb the social ladder, to what extent does the new middle class find the acquisition of social and cultural capital a dynamic, static or sluggish process?

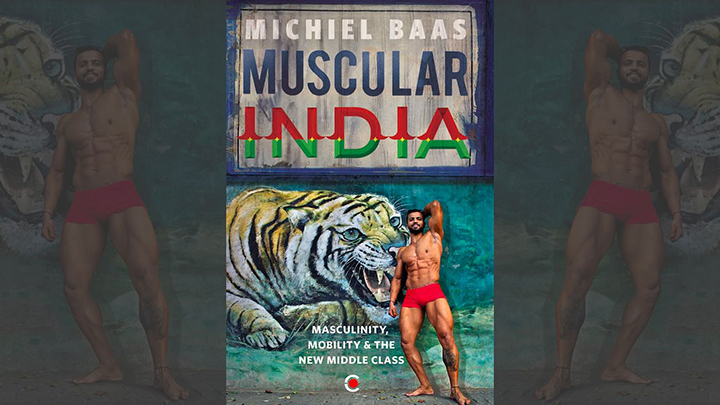

These are some of the key questions with which anthropologist Michiel Baas’s new book — Muscular India: Masculinity, Mobility & the New Middle Class (Westland/Context) — embarks on an inquiry into the social settings and aspirational trajectories of the new middle class in India. More interestingly, Baas addresses these questions with the prism of the new male body ideal, of a lean and muscular physique, in post-liberalisation India, and the new middleclass professionals engaged in helping their well-off clients pursue the goal of bodily transformation.

The book tracks ideas and people associated with the aspirational body type, the fitness industry, and bodybuilding as a competitive sport to study the social processes, evolving ideas of masculinity, and the class matrix in urban India. In doing so, Baas blends academic training with general accessibility to appeal to a wider readership interested in examining different facets of middleclass India.

As Baas draws on his research, conducted on and off during a 10-year period and supported by Nalanda University, he follows the careers and life trajectories of various personal trainers, gym instructors and bodybuilders in four metropolitan cities: Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai and Bengaluru. For some inexplicable reason, the eastern metropolis of Kolkata is missing and hence, one may quibble over the fact that eastern India goes unrepresented in the narrative scheme of the book.

The new lean-muscular ideal — of “bulging biceps, rock-hard abs, and visibly pronounced pecs” — can be seen as a ripple effect of pop culture portrayals in, for example, Bollywood. This, in turn, could be the influence of the imported ideals accompanying greater global exposure, or the imprint of the Indian editions of publications like Men’s Health.

However, the new form has been a point of departure from the bulky strength of a body type represented by the milk and ghee-nourished pehelwan. While the pehelwan’s body type had the philosophical tinge of a way of life, the new body type was a transformative aspiration as well as a career opportunity for a new type of professional in urban India: the gym instructor, the fitness entrepreneur, and the personal trainer.

These professionals were beneficiaries as the ambit of fitness went beyond the health concerns of weight loss or control, to include ideas of “being professional, cosmopolitan, and in control to withstand the brunt of overconsumption”. Gyms became a site where the new middleclass trainers interacted with a pool of clients who came from the upper middle class or the middle of the middle class, and also with a governing idea of middle classness defined by their clients. A template of middle classness was anchored by notions of dyads like the English-speaking — the vernacular, cultured-boorish and the original and the new entrants “mimicking” to look the part also forms part of this interplay at gyms or even personal training at home.

Baas writes:

“Their bodies function almost as a currency in this; it buys them a way into something that would have otherwise kept its doors resolutely shut. At the same time, these relationships between trainers and clients continue to be revealing for the boundaries that separate different layers of the Indian middle class, pointing at the entrenched hierarchies. As much as change and limitless opportunities characterise the narrative of a new and rapidly changing India, upward socioeconomic mobility can be a pretty sluggish process as well.”

Baas follows bodybuilders, gym instructors, and personal trainers like Kishore and Vijay at Chembur in Mumbai; Victor in Karapakkam, Teynampet and Palavakkam in Chennai; Manish, Amit and Ravi in CR Park and Chirag Dilli in Delhi; and Akash in Richmond Town in Bengaluru.

Particularly fascinating is the journey of Shivam in Delhi, whose attitude ranges from spells of ambition and exultation to cynicism and finding his pragmatic core. While all of them represent diverse experiences in the fitness industry and bodybuilding scene in India, they also converge on points of exploring maneuverability within the middle class space in contemporary India.

Almost parallel to these narratives, the book shares observations on elements of continuity and change in the social fabric, spatial patterns, and the demography of the urban landscape of India. In this context, the chapter on the “engulfing villages” — about the expansion of the National Capital Region, and examining the hold of Jat and Gujjar communities on the bodybuilding scene in the capital — is of particular interest. To add to that, the book does well to probe the attitudes towards their suburban presence, as trainers in gyms catering to tony upper middleclass clients in the upscale colonies of the city.

In some ways, the book also explores the new possibilities and the old constraints and challenges that come in the way of a new generation of men trying alternative and non-conventional career paths.

However, one of the more important perspectives shared by Baas is how his research refutes the idea that the urge to sweat for muscular frames represents a crisis of masculinity in India. It’s an idea that has been expressed more frequently in the wake of recent cases of sexual violence in the country. The book doesn’t find merit in this line of reasoning.

Baas writes:

“The idea that India is gripped by a crisis of masculinity, compelling its men to pursue even more muscular bodies, even to the point of pain, does not resonate with the way trainers and bodybuilders themselves engage with their bodies and the various insecurities, uncertainties and the issues of precarity. My research actually suggests that working out, and the goal of a muscular body, reflect an acceptance of the reality of society on steroids instead.”

He uses the phrase “society on steroids” to describe a society which is in a hurry, out of control, and racing away to uncertain realms.

Although devoid of detailed treatment, the book touches upon related issues like that of adulteration of supplements, counterfeit products, and substance abuse. At some places, the cluttering of too many themes in a narrative-commentary frame impedes the flow. While the copious references to scholarly work and research on some of the themes that surface in the book would be of immense value to serious readers, the general readership would have preferred them to be shifted to the notes section at the end of the book.

Similarly, some of the themes, like the one on unsure attempts at defining the size of India’s middle class, could have been developed as separate chapters. The bibliography at the end is well-compiled and would prove helpful to anyone willing to explore more on the subject. If I’m pressed for more nitpicking, there’s a typographical error; “Vijay” in Chapter 1 is somehow “Vinay” in Chapter 3.

In tracing one of the less noticed, and far less examined, strands of mobility within middle class India and their constraints, Muscular India is an important contribution to the understanding of urban India. As a project of self-fashioning, to borrow a historian’s description, still explains the nature of the Indian middle class, the book shows new ways of looking at the new entrants and the influential gatekeepers of this project in urban India.

www.newslaundry.com