In the heart of Delhi, where the towering walls of Tihar Jail house over 13,000 inmates—more than 250% of its sanctioned capacity—an ambitious experiment in rehabilitation has quietly been losing steam.

Once hailed as a model of self-sustainability and reform, Tihar’s homegrown brand, TJ’s, has long stood at the intersection of incarceration and entrepreneurship. Launched in 1994, three decades after the Tihar Haat vocational training initiative began, TJ’s was envisioned as a platform for inmates to learn skills, earn stipends, and reintegrate into society with dignity.

But recent data accessed by Patriot paints a grim picture.

Numbers tell a story of steady decline

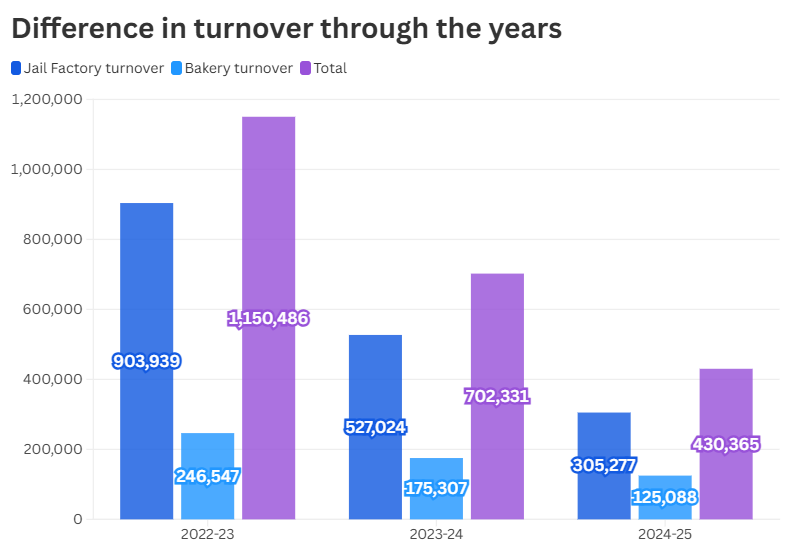

From earning Rs 11,50,486 in 2022–23, TJ’s saw a sharp 38.9% drop in turnover to Rs 7,02,331 in 2023–24. The following year, 2024–25, the decline continued—this time by 38.7%—bringing in a mere Rs 4,30,365.

Once a brand that drew in double-digit crore revenue, TJ’s now struggles to survive in a market that has moved on. And while the earnings have plummeted, the costs associated with running the initiative have continued to rise.

“In 2023–24, the prison department was having to pay Rs 1.18 lakh to a contractual staff member for supervision and delivery of raw materials,” said a source familiar with the financial workings of the programme. “However, that amount had increased to Rs 1.44 lakh in 2024–25, in the space of a year.”

Pandemic effect and the failure to digitise

According to a senior official, the brand’s decline cannot be pinned to a single moment—it was gradual, shaped significantly by the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Earlier, the initiative still had its novelty about it but after the pandemic nobody cares about it,” the official said. “Moreover, the quality may have also deteriorated since during the pandemic not many people were left who knew how to impart proper training. Moreover, we had also paused our sales for some time.”

The pandemic also shifted much of the retail economy online, but TJ’s was left behind. “The proposal is still stuck in the paperwork phase. Nobody knows when it will come about but we are still hoping for the best. Maybe then it will enable us to gain a greater share in the market,” the official added.

A digital promise that never materialised

Back in December 2022, there was renewed hope when the prison administration announced plans to take Tihar Haat online. The products on offer included cupcakes, stationery, and handicrafts. Then Director General (Prisons), Sanjay Baniwal, had expressed confidence that the move would scale up the brand while maintaining product quality.

“We’re modernising to align with contemporary market demands. By approaching online retailers, we aim to scale up our business,” Baniwal said at the time.

His approach was rooted in sentiment. Many patrons of TJ’s had an emotional attachment to the initiative, seeing it as a way to support inmates in rebuilding their lives. The idea worked—at least for a while. In the financial year 2018–19, TJ’s clocked sales of Rs 18.6 crore.

Then came the fluctuations.

Shrinking presence across the city

With sales faltering, the number of Tihar Haat outlets in Delhi also shrank. From 13 in 2018–19, only five remain today—located at the Tis Hazari Court Complex, Rohini Court Complex, Kiosk No. 13 in the Delhi High Court Complex, the Lawyers’ Chamber Block in the Dwarka Court Complex, and the Pusa Institute Complex in New Delhi.

At Tis Hazari, a supervisor described the current state of business as dire.

“There are barely any visitors nowadays. Especially now, with the courts going on their summer vacation, the number of people coming here also drops significantly. We are just hoping that when the courts reopen, we have enough raw material to sustain ourselves,” he said.

Beyond the court complexes, TJ’s products once reached private outlets as well. After the pandemic, 20 private stores across the city stocked its goods. Now, not a single one does.

Vinay, shopowner of Raghunandan at Ashoka Hotel, recalled when authorities withdrew TJ’s products from their shelves. “It has been quite some time that the TJ’s brand stock has been pulled down from the shelves. With decreased interest among shoppers, it made no sense to have them on. Even shoppers were not inclined towards buying them, since the novelty of buying products from Tihar Jail only stays for so long,” he said.

From novelty to suspicion

The decline is not just about numbers—it is also about perception. At the NDMC Market in Netaji Nagar, a worker—speaking on condition of anonymity—pointed to an erosion of trust in the brand.

“They know that what they are getting is worth much lesser than other brands. However, it is not just the price but also, the question of who is making it that also makes a feeling of doubt emerge within buyers,” he said. “The moment they hear that it is from Tihar Jail, they become a bit concerned and more apprehensive about buying products. It has, especially increased now after the prison authorities failed to make inroads with the newer generation and move digital.”

“They know that what they are getting is worth much lesser than other brands. However, it is not just the price but also, the question of who is making it that also makes a feeling of doubt emerge within buyers,” he said. “The moment they hear that it is from Tihar Jail, they become a bit concerned and more apprehensive about buying products. It has, especially increased now after the prison authorities failed to make inroads with the newer generation and move digital.”

Government clients and wages for inmates

Despite its waning market appeal, TJ’s continues to cater to government institutions, including schools. Much of the wooden furniture used in these institutions is still manufactured by Tihar inmates.

The vocational training programme at the jail employs approximately 1,500 inmates. As of 2023, they are paid Rs 17,234 per month for unskilled work, Rs 18,993 for semi-skilled work, and Rs 20,903 for skilled work.

A looming relocation

Meanwhile, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led state government has set aside Rs 10 crore for consultations to relocate Tihar Jail to a larger space. With more than 13,000 inmates crammed into a facility built for fewer than 5,000, the move is seen as necessary.

Also Read: Inmate’s Instagram reels reveal smuggling inside Tihar jail

But the funding is not meant for reviving TJ’s.

For now, the once-ambitious rehabilitation brand is at a crossroads—caught between a legacy of reform and a present of fading relevance.