Safety of journalists covering war affected areas is also the responsibility of their employers

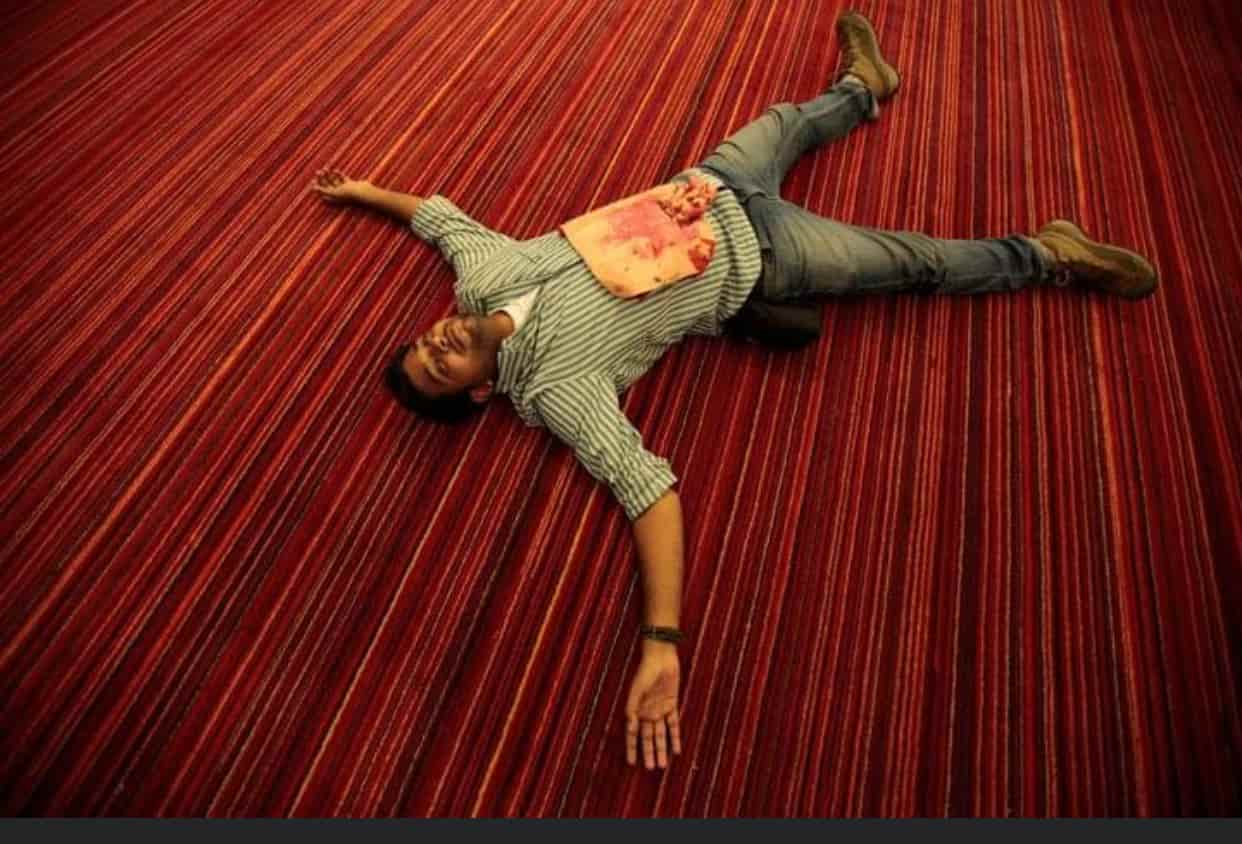

Photojournalist par excellence, Danish Siddiqui, died at the hands of the Taliban in Afghanistan. Danish was there to cover the Afghan conflict that was triggered by the recent decision of the new Biden administration in the US to withdraw all US and NATO forces from the country.

Danish’s work was even known to his killers, who later expressed regret to a leading news channel “We were not aware during whose firing the journalist was killed. We do not know how he died,” Zabiullah Mujahid, a Taliban spokesperson told New18, and added, “Any journalist entering the war zone should inform us…. We are sorry for (the) Indian journalist Danish Siddiqui’s death.”

Siddiqui had been in Afghanistan for a month, and on July 16 Siddiqui headed to Spin Boldak with Afghan commandos. As per his employer, Reuters, Siddiqui had informed them of a shrapnel injury on his arm in an ambush, a few days earlier. Despite this, he was not pulled out. The statement merely says “He was treated and Taliban fighters later retreated from the fighting in Spin Boldak” without giving any details of the nature of the wound and what Reuters did to make sure he was fit enough to operate in a war zone.

That’s a pitiable state of affairs, one the best talent and a bright career is cut short, and the agency of such great repute only comes up with a vague statement. Their staffers and some of the foreign correspondents based in Delhi, who often travel to Pakistan, Burma and Afghanistan are concerned about the safety net of journalists, and hold the media organizations responsible for lack of it.

A South Asia correspondent of a leading publication in Europe, let’s call him John, in his mid-30s has been in India for many years, can speak good English and rudimentary Hindi, is aghast. He is not allowed by his employers to express his views on this issue in public but feels strongly about it. An injured photographer killed poses many grave questions. “The employers—news agencies—can not shun their responsibility,” he says when a journalist dies reporting.

He has been to Afghanistan and Pakistan many times and is aware of the anti-India sentiments, and wonders why journalists from other countries are not sent if nationals of a particular country are a “pet target.”

When he travels, keep in touch with the local authorities, especially when venturing out of the city, also the envoy of his country is taken into confidence. John points out that there is a well laid out charter for the safety of journalists working in war zones and dangerous areas. It’s a professional hazard: the safety of scribes cannot be guaranteed. But, International law provides protection on paper, though it is not followed on the ground. “They—both staffers and freelancers—have to be provided basic protection, compensation and guarantees from their employers,” he says.

Reporters Without Borders, with its headquarter in Paris, promotes and defends the freedom to be informed and to inform others throughout the world has laid down eight principles for the safety of journalists sent to cover stories in dangerous parts of the world, stressing that the media management of the employer “have their own responsibility to make every effort to prevent and reduce the risks involved.

The eight principles being: 1-Commitment: systematically seek ways to assess and reduce the risks by consulting each other and exchanging all useful information. 2-Free will: involves an acceptance by media workers of the risks attached, also, they go on a strictly voluntary basis; have the right to refuse assignments without explanation and without there being any finding of unprofessional conduct. In the field, the assignment can be terminated at the request of the reporter. Editors should beware of exerting any kind of pressure on correspondents to take additional risks. 3–Experience: requires special skills and experience, so editors should choose staff or freelancers who are mature and used to crisis situations. 4–Preparation: regular training in how to cope in war zones or dangerous areas will help reduce the risk to journalists. 5-Equipment: reliable safety equipment (bullet-proof jackets, helmets and, if possible, armoured vehicles), communication equipment (locator beacons) and survival and first-aid kits. 6-Insurance. 7-Psychological counselling.

Last not the least, 8-Legal protection: Article 79 of Additional Protocol of the Geneva Conventions, provided they do not do anything or behave in any way that might compromise this status, such as directly helping a war, bearing arms or spying. Also, any deliberate attack on a journalist that causes death or serious physical injury is a major breach of this Protocol and deemed a war crime.

John points out that safety is an issue, and employers have to be pulled up for and held accountable. Many of the European news agencies, some of the editors are his friends, hire young people from their own country, freshly out of college looking for some adventure. They are paid in Euros, money remitted in their account back home, while they work here as interns, usually for six months, on a tourist visa. They get sent for various assignments and are paid higher than the Indian staff for the same job though are far more experienced.

A couple of weeks back, an India based New Zealand origin blogger Karl Rock was blacklisted. Though he didn’t represent any agency officially, claims to be a traveller, shifted to India 2 years ago and since has married an Indian woman. His Indian visa was cancelled while he was travelling to Dubai and Pakistan. In Dubai, he tried to get the visa renewed, and was informed that the Indian authorities have blacklisted him.

Karl Rock thinks the reason is his youtube videos critical of the government and in support of the anti-CAA protests in 2019. However the sources in the Union Home Ministry clarified that the action was taken against him for violating the terms of his visa, as it was found that he was doing business—earning a livelihood—on a tourist visa, also violated other laid conditions, and on at least three occasions visited restricted areas that are not allowed for foreigners, particularly those on a tourist visa. Journalism and other media activities are not touristy activities, cannot be done without the requisite permission from the local government is an established norm. Taliban also pointed it out in their statement regretting the demise of Danish Siddiqui. Reuters need to clarify.

Karl Rock is not an exception, there are many foreigners who come on a tourist visa and report for publications and channels in their native countries as stringers or interns. Foreign publications prefer them as they are much cheaper than having to employ a correspondent or two. “They (the publication) avoid paying taxes here in India and in their own country. Also, it is illegal in their native country as they do not adhere to the legal employer-employee relationship, and provide necessary safeguards and take safety precautions,” Paul points out.

The situation is not much better with those who have staffers as the recent unfortunate demise of Danish Siddiqui proves.