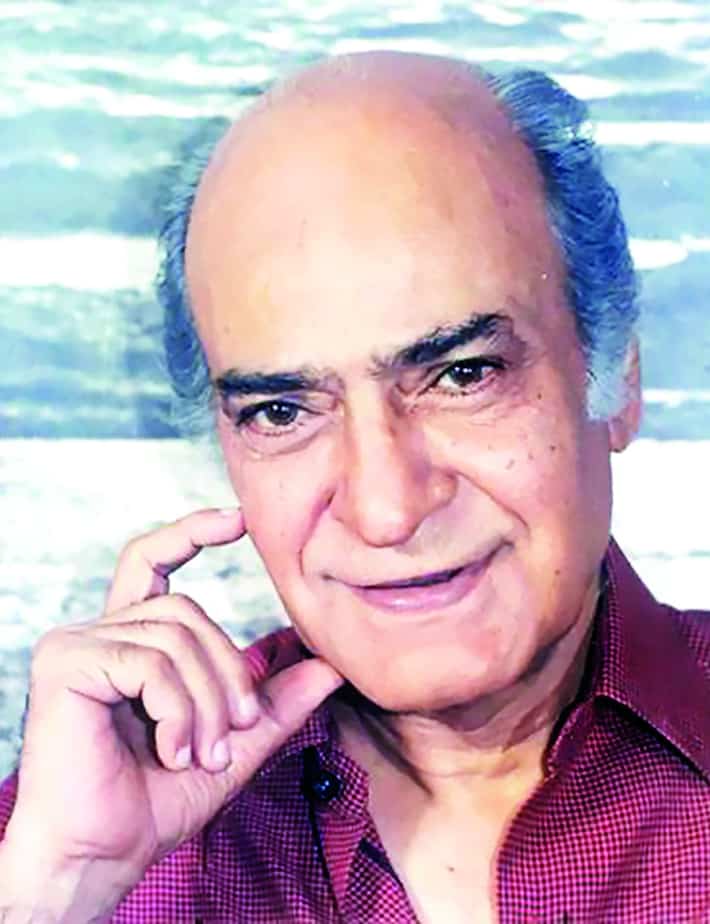

As an old Rishi Kapoor and an older Amitabh Bachchan come to a screen near you in 102 Not Out, a tribute to the ever-old man of Hindi cinema, AK Hangal

As the resolutely old are set to find a story celebrating a centenarian on Hindi screen this Friday in Umesh Shukla’s 102 Not Out, one may revisit the memories of one of Hindi cinema’s most understated taken-for-granted grandfathers. In his own serene and unhurried ways on the margins on the Hindi screen, AK Hangal (1915-2012) was a comforting presence, especially for those for whom being eternally old isn’t such a bad idea.

It was perhaps a reminder of how unnoticed he went that one was tempted to describe his passing away in his most insignificant role — that of Rahim Chacha (Imam Sahab) in the 1975 blockbuster Sholay. Five words gave him his slice of identity in the film: “Itna sannata kyun hai bhai?” (Why is there such a lull?).

Your memories of AK Hangal might not place much premium on youth, but his younger years were remarkable in their own ways — as a theatre artist traversing the years before and after independence (1936-45), and as a member of the Left-leaning Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). But chronicles of his journey may conceal something that nudges our collective memory about Hangal Sahab — the dignity of his ordinariness, the grandfather next door.

In his frail anatomy, feeble voice and reassuring parental presence, one could live the possibilities and limitations of his life and times. For a man who started his cinematic journey at the age of 50 and stuck to his non-filmy sounding name Avtar Kishan Hangal, the typecasting in character roles was as “normal” as the conventions which guide the stereotypes of the film industry. But, in carving a niche for himself in the confines of those stereotypes, Hangal Sahab had a kind of taken-for-granted presence in the family narratives of Hindi films. Similar to that of a no-maintenance but ever reliable piece of old furniture in a cosy corner of your house.

There were lazy reasons cited by filmmakers for typecasting him in a slot. However, when they did try him in a different shade, the results were interesting and even produced an often narrated anecdote. As film critic Ziya Us Salam once recounted;

“Perhaps it had something to do with his face that filmmakers were loath to offer him a villain’s part. Yes, of course he did break the mould sometimes, as in Shaukeen, where he played, along with Ashok Kumar and Utpal Dutt, a lecherous old man. That he acted with conviction is reflected in the following anecdote. Hangal, well into his 90s then, had finished a leisurely dinner at a five-star hotel in Delhi and needed to be dropped off at a friend’s place. A girl in her 20s was assigned the task of driving him. She whispered in trepidation to her boss: “Sir, I have seen Shaukeen!” Finally, a man had to be commandeered to drive Hangal where he wanted to go.”

In the post-Nehruvian times of Hindi cinema’s engagement with the shifting sands of urban family structures and rural social milieu, he somehow symbolised elderly grace of a bygone era. Never rushed even in moments of histrionics. One word at a time.

Just exercise your memory. Can you really put out of frame the effortless and understated civility with which he played father to Jaya Bhaduri in two very different situations in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Guddi (1971) and Abhimaan (1972)? Perhaps not. And how lingering are the memories of his restrained act as Ramnath Sharma in Bawarchi (1972), who beyond regular arguments has a regret of not being able to send his brother to Cambridge? Hangal Sahab could hold his own glow in a galaxy of star-centric film narratives.

And that’s why you can’t forget h

is presence in even blink-and-you-miss roles, as in the star-studded Sholay. Ramgarh’s quest for religious diversity found an answer in his role as Imam Sahab who loses his son to Gabbar’s terrorising ways. Just blink, and you would miss this iconic one-liner which (though not the most poignant of his cinematic moments) has become synonymous with his name.

In 1999, his autobiography Life and Times of AK Hangal (Sterling, 1999) was published. Besides offering interesting perspectives on his eventful times in personal and public space, the book revealed a hidden film critic in him. Turning his critical gaze on Hindi film industry, he lamented the proliferation of stereotypes which inflict cinematic narratives in Bollywood.

He deserved a careful biography too. In 2006, when Mumbai-based writer and journalist Jerry Pinto’s book Helen: The Life and Times of an H-Bomb was published, two thoughts crossed my mind. One, it was significant in the genre of Bollywood biographies because it was the first serious attempt to have a biographical narrative on the fringe figures (villains/vamps/comedian/character actors) who caught the cinematic imagination in their days.

Two, one thought what a great topic Hangal Sahab would be for such a biographical account. In living and observing the evolutionary strands of Indian theatre and mainstream Hindi cinema from the sidelines, he could have been the stuff of any biographer’s delight.

It has been said that a film actor is one who grows insecure when he is not recognised from two paces away. This does not hold water for Hangal Sahab. He sneaks into your memory in his own nonagenarian ways; never seeks to barge in. He missed his birth centenary by three years.

In the portrayal of our limitations that sink in with greying hair and in embodying the endearing civility of the old world, the defining quiver and poise in AK Hangal’s voice would stand out in the cinematic cacophony. In our vicarious engagement with old age on the silver screen, Hangal Sahab was a site that we visited so many times. He didn’t disappoint. When old age met effortless grace next door, Hangal Sahab was there.