A poor man sold the jewellery of his beloved to build a Taj for her. An extraordinary story of love and loss….

Urdu poet Sahir Ludhianvi famously wrote about the Taj Mahal, Ek shahanshah ne daulat ka sahara le kar, hum girbo ki mahubat ka udaya hai mazaka (One emperor, with support of his wealth, has ridiculed love of us, the poor).

There’s no denying the fact that only an emperor, Shahjahan, could have celebrated his love Mumtaz Mahal by building the magnificent Taj Mahal. But there’s a poor man in Aligarh who didn’t seem to agree with Ludhianvi.

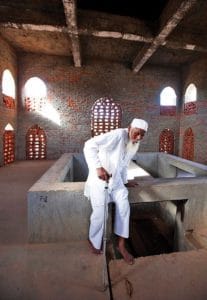

A retired postman, Saidul Hassan Qadri, in his early eighties, died last week when he was run over by a speeding car. Five years ago, he had built a mausoleum for his beloved wife, Tajammuli Begum, soon after her demise. He’s now laid to rest next to her. In that sense, Qadri’s fate is not very different from that of Emperor Shahjahan. Also, his story no less exceptional.

Qadri, a resident of Kesar Kala in Bulandshahr district in Uttar Pradesh, was married to Tajammuli Begum for 50 years. They had no children, therefore, the two were the sole fulcrum of each other’s life — neither wanted to outlive the other. Tajammuli was lucky in that sense. She died of oral cancer, her addiction of chewing betel leaf or paan her final undoing.

Before she died, she’d often complain, “We have no children. Who’ll read Fatihah when we die.” Fatihah is the first chapter of the Quran, has seven verses, and is read out loudly before burial.

When she died in 2012, Qadri decided to celebrate her life and his love for her by constructing her mausoleum. He entrusted the task to an architect friend in Aligarh, who made a plan. He paid a local bricklayer Rs 1 lakh to actualise his dream.

Finally, the plan was not followed and the mausoleum became a product of Qadri’s imagination, an imagination inspired by Taj Mahal. The construction started on July 3, 2012, under the shadow of dark monsoon clouds. He sold his precious belongings, even the jewellery of his deceased wife, to fund the building of her mausoleum. A poor man’s Taj Mahal was built in a few months.

But he’d be offended if anyone referred to the mausoleum as “the little Taj”; he had a name for it — Maqbara yaadgare mohabbat (Mausoleum memorabilia of love). He even penned a poem, “Na koi Sheeshmahal na koi Taj Mahal…. Hai yaadgare mohabbat, yeh pyaar ka hai mahal!” (It’s neither a palace of glass nor Taj Mahal; it’s in memory of my beloved, this is the palace of love.)

Despite his protestations, it’s more than obvious that his palace of love is inspired by the Taj Mahal. He had lived in Agra for some years in his formative days when he trained as a cleric. He admires the idea and purpose of the Taj Mahal.

History repeats itself in strange ways. The location of Maqbara Yaadgare Mohabbat was carefully selected so that he could gaze at it from a window of their home. Admiring the resting place of his beloved wife was his way of reliving her memory long after she left for her heavenly abode. Shahjahan, too, spent the last few years of his life admiring Taj Mahal across the river Yamuna, from a window in the Agra Fort, where he was under house arrest on orders of his son and successor Aurangzeb.

In the dusty landscape of western Uttar Pradesh, in the middle of nowhere, stands this monument of love rather unapologetically. News photographer Raul Irani took some pictures which were first published in Open magazine in 2013.

Qadri, resident of an obscure town, became an overnight sensation. His love saga was reported across the globe by the international press, captured the imagination of people. And there were many who were more than willing to offer him pecuniary help to finish the mausoleum as a tribute to their own loved one.

Not just individuals, but maulvis, politicians, even international organisations made a beeline to support his cause. Qadri refused them all. He wasn’t sure if the donation money is halal (pious) and he didn’t want his monument of love to be desecrated by using haram money (ill-gotten wealth).

The international coverage made him a local hero. The then district magistrate of Bulandshahr, B Chandrakala (Qadri recounted this to Raul Irani on one of his many visits) organised a meeting with the then chief minister, Akhilesh Yadav. Yadav offered him help to procure fine marble from Jaipur to finish the mausoleum – the rural Taj Mahal of the poor. He refused any help. It remained unfinished. That makes it beautiful. He approached Wakf Board to take care of his monument of love after his demise.

Qadri wanted to construct a school in a small plot of land next to the mausoleum. Some influential local maulvis offered help on the condition that it would enroll only Muslim children. He was against discriminating on the basis of faith. The school was never built.

In the last few years he aged fast, couldn’t walk without the support of a stick. His end came when he was mowed down by a reckless driver. He was taken to an Aligarh hospital where he was declared brought dead.

A large crowd gathered as he was laid to rest beside his beloved. “Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage,” said Lao Tzu, an ancient Chinese philosopher. Qadri was a brave man in love.