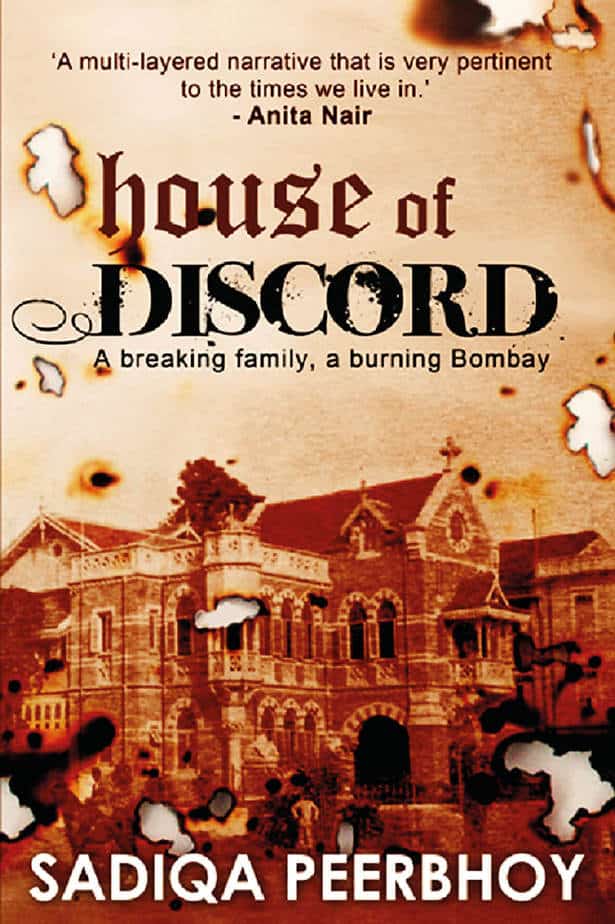

An extract from House of Discord by Sadiqa Peerbhoy, set in 1992 Mumbai, where the life of a family gets inextricably tangled due to the communal riots sweeping the city

He jammed his foot on the accelerator. Thankfully the rush-hour traffic had dwindled down and he could speed towards Kala Ghoda where Salma was waiting for him in the restaurant with that tight little knot between her brows, her fingers playing with the salt and pepper cellars self consciously aware of being alone at the table. God how he loved her!

So he had been rash. Love made one do crazy things. He, at least, had done the honourable thing. He had married her when her guilt over the occasional sex had made her remorseful. Every ardent lovemaking session that made him feel he could burst into a happy song on the top of his voice, had made her weep for hours afterwards.

‘Sweetheart,’ he had pleaded with her stroking her long hair into place, ‘We love each other. Sex is a natural expression of our love. What makes me so happy, so fulfilled, shouldn’t make you cry. Tell me, do you think that we are doing something wrong?’

‘You saw how the receptionist leered at me.’ Salma continued to wipe her eyes and nose with a corner of her blue dupatta.

‘Alright,’ he had said, swinging his legs off the bed with its crumpled bed sheets and shrugging into his shirt in one swift decisive moment. ‘If it makes you feel better, we willget married and to hell with our families.’ A post-coital decision made on the crest of a sated moment.

In the sluggish heat of a late Wednesday morning, they had driven to the Registrars’ and collected the multiple forms of the Special Marriages Act. They required proof of residence and identification along with passport pictures. It took them two days to get all the documents together and file the papers with a clerk who sat excavating his ear with a pencil. A month later they went with three friends and waited for about an hour, jostling with touts, small-time lawyers and estate agents on wooden benches making weak jokes to tide over their nervousness. Finally the peon who had from the first zeroed in on them for a hefty bribe, gestured them into the glass-panelled cubicle and flipped pages of a much-filled ledger to paste their two photographs side by side.

The Registrar had sweat circles under his arms and apostage stamp of a black moustache. ‘Neeext,’ he called, ensconced behind the green baize-covered desk. He looked at Salma between flipping through their documents. ‘Someone is forcing you to get married, Miss?’ Salmashook her head. ‘Okay then,’ he said putting a decisive stamp on their forms. ‘You sign here. Witnesses sign here. Chalo bhai. Marriage okay. Congratulations. No divorce, you understand? Too much divorce these days. Who is neeext?’

Then he had looked at them with the ponderous smile he thought the occasion warranted. ‘Come next week, okay. Collect your certificate. You are now legally Mr and Mrs. Okay?’ Then he turned aside to sip tea from a chipped blue cup. The peon outside smiled ingratiatingly.

Salma and Rajan looked at each other, a little fearful of what they had just done. ‘So Mrs Okay. . .are you okay?’ Rajan joked to cover his nervousness. Happiness, apprehension, fear wafted liked dry leaves across their faces. Married. Now come what may. Then the friends were crowding them and handing them strings of marigold togarland each other. The box of saffron sprinkled sweets was doing the rounds as strangers around smiled and congratulated them and remarked on the radiant glow of the bride who kept her head down.

They stepped out of the greeny tube-lit government office whose corridors smelled of old urine, into the greedy sunshine. And blinked. It was surprisingly, a very ordinaryday caught up in the busy chaos of mid-morning Bombay. But there was something different about the quality of the light.

A wistfulness about the cloudless blue sky. Like a benediction. The city seemed to shrink away and distance itself. Even the faces around them looked different. Suffused with a glow. They looked at each other in silent wonderment. Man and wife in the eyes of the law. Their lives transformed irrevocably. Their eyes smiled at each other. Salma’s lips trembled.

Salma had worn a pink and gold sari and flowers in her pinned-up hair. He had come in his work clothes, taking the afternoon off. The two friends, Tasneem and Reeta from Salma’s office and Joseph, Rajan’s school friend, insisted on taking them out for a celebratory lunch at Ali Baba’s down the road. Then they went back to theirrespective offices. The honeymoon would have to wait. Rajan had booked them into Hotel Ritz at Churchgate for the coming weekend. An extravagance. But for thefirst time they would check into a hotel as Mr and Mrs Deshmukh. Legitimately. Even if the receptionist at the hotel looked at them with that knowing grin of complicity, it wouldn’t matter.

It was one thing to go to a Registrar and get married secretly, quite another to face up to the consequences of this act. Rajan had no illusions about the quake this would create in both the families and their hostile communities. Especially in these troubled times when the controversy over an unheard of mosque in Ayodhya was snowballing into a national issue with Hindus and Muslims on opposite sides of the fence — drawing firm divisive lines in the very psyche of India.

Salma was a Muslim. She belonged to a sect which followed a living leader, an Imam, who ruled the community with an iron hand. The Bohris were likely to be excommunicated at the smallest misdemeanour. The whole family would be out in the cold if even one member broke the unbending rules that kept the community insular. No member of the family would be allowed to be buried in the community graveyard or even enter the communal Jamatkhana. The community would close its ranks against all of them and mete out a lifelong punishment too severe to comprehend.

Salma had dared to marry him… a Kokanastha Brahmin. A secret marriage, when it was planned, had seemed rebelliously romantic and a validation of the love that was gloriously unaffected by their differences. What did love have to do, anyway, with the way one worshipped? He attended, or rather was forced to sit in on all the poojas, havans and shraadhs his Mother organised at home. He helped fix up the blinking fairy lights for the five days of Ganpati festival every year at home and danced all the way to Chowpatty when the idol was being taken for its ritual immersion. In the month of Shravan, he looked forward to the special fare cooked every Somwaar and the varan bhaat that his mother made in pure ghee. Occasionally he dropped by at a nearby Ganpati temple to pray for success…

The book, published by

Readomania, costs Rs 295/-