History gives a clear message: Students are the harbinger of positive change. They will prevail sooner or later

The student stir against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) is the most recent example of students being the harbinger of positive change in the polity and society in favour of a liberal and democratic ethos. And in many cases, they have been successful. Even when their movement was suppressed and they were killed in large numbers, they sowed the seed of change.

History stands witness that student movements should never be taken lightly — suppression doesn’t quell the movement but instigates it, spreads it across various parts of the country. Students protesting against CAA is no exception. It started in Delhi and has now spread to various parts of the country, including Banaras Hindu University, a national university of repute located in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency.

The use of force against students only instigates them to further action. The best example is the Bihar Movement which became a pannational movement— Total Revolution (Sam-purna Kranti)—under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan. In February 1974, students from Patna University formed Bihar Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti (BCSS) that had members from the whole of Bihar — included the likes of Laloo Prasad Yadav, Nitesh Kumar, Ram Vilas Paswan and Sushil Modi, to name a few. They were agitating against the education system and poor quality of food in hostels. They gathered outside the Bihar Assembly in Patna on 18 March 1974, protests turned violent, resulting in arson and damage of public property. The police action led to the killing of three students, followed by a state-wide strike five days later.

A local student agitation germinated into a potent political resistance movement across the country. The then prime minister Indira Gandhi dismissed the Bihar government under Abdul Ghafoor but couldn’t contain the student stir. And as they say, the rest is history. It’s pertinent to point out that the Bihar Movement had the support of student outfits like Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) — connected with Jana Sangh, now the student wing of the BJP and also All India Students Federation (AISF) connected with Communist Party of India. Both Left and Right wing students had joined hands for a common purpose. Late BJP leader Arun Jaitley actively participated in Delhi.

Quite in contrast with what’s happening now. ABVP — like a government agency — is clashing with the National Student Union of India (NSUI) and Left-affiliated students in Delhi University and with SFI in Kerala Varma College in Thrissur who are protesting CAA. There’s an effort to scuttle the students’ movement on party lines.

Then the Mandal agitation by students against caste-based discrimination on government jobs led to brutal repression in the late 1980s. There was widespread chakka jam or blocking of roads and highways; bandhs, hartals, and dharnas were successful. At the peak of the protests, in September 1990, a 20-year-old student of Delhi University’s Deshbandhu College, Rajeev Goswami, set himself ablaze against Mandal Commission’s recommendation to reserve 27% of government jobs for Other Backward Classes (OBC) in Delhi. He became a household figure and was subsequently elected as the president of Delhi University Students’ Union.

These agitations had a profound impact on India’s polity. They resulted in the political regrouping of the OBC, strengthening of regional parties in the Hindi belt, ending the dominance of the Congress party. The student leaders of Sampurna Kranti movement 15 years earlier, Mulayam Singh Yadav and Laloo Prasad Yadav, were to become the chief ministers of UP and Bihar respectively, on caste-based platforms, seen as a legacy of the Mandal Commission recommendations.

In other nations

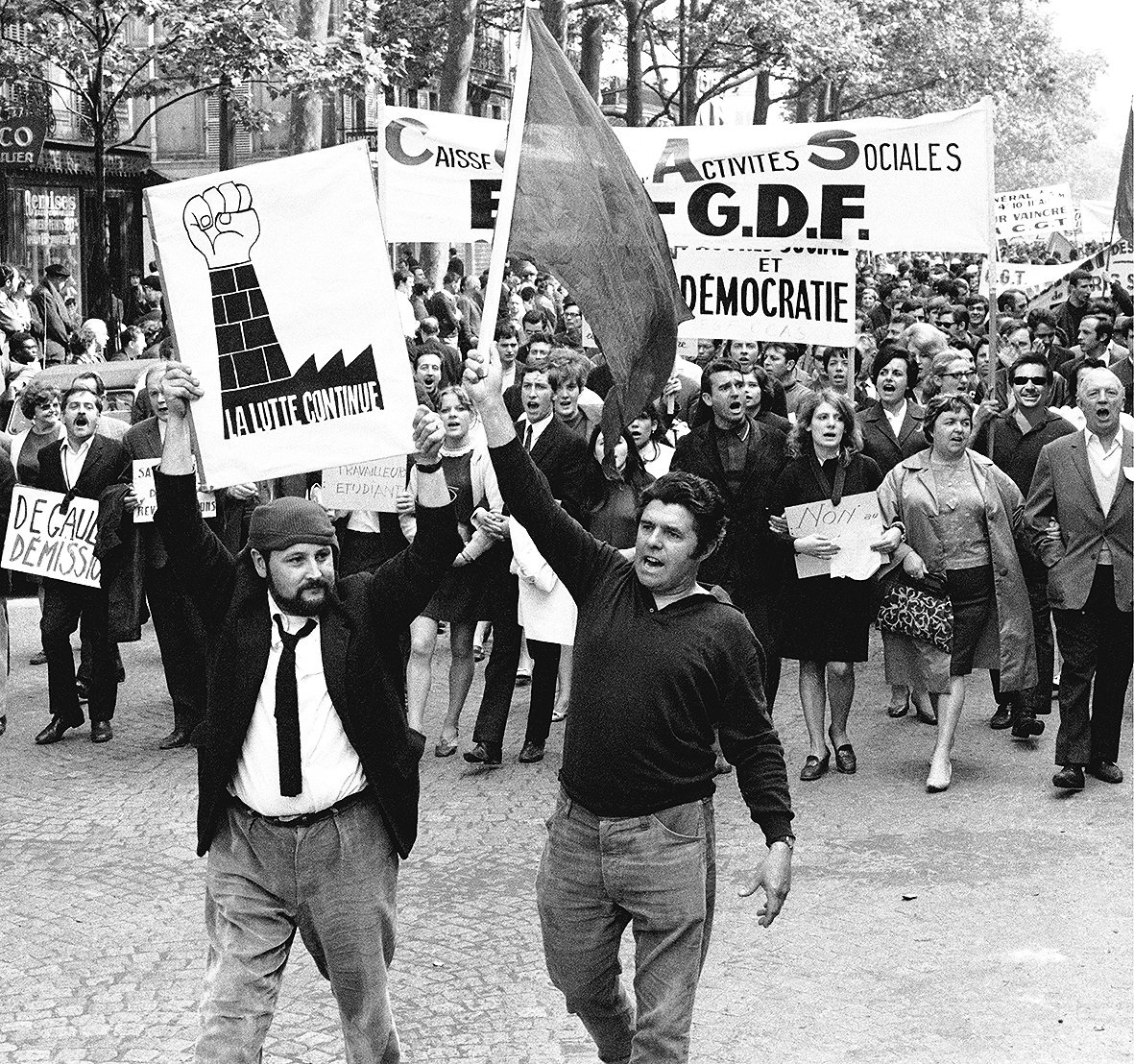

The year 1968 is famous for global student agitation. The unifying force was television: Students were aware of and inspired by their counterparts in other parts of the world. It was about modernity — an idea that has always fascinated young minds — whether in Paris, Prague, Mexico, New York or Rome. In his famous book 1968 — The Year that Rocked the World, Mark Kurlansky points out that at a time when “nations and cultures were still separate and very different.” Despite this, “There occurred spontaneous combustion of rebellious spirit” amongst the youth. It was organic in character, was largely not planned and not organised, important decisions were made “on a moment’s whim” was primarily “leaderless or had leaders who denied being leaders.”

The student movement was directed against the authority, the state — in communist countries it was against communism and in capitalist countries against capitalism. It was for civil rights, against the American war in Vietnam, was directed against racism — the same year “Negros” become “Blacks”, anti-colonialism, for gender equality, feminism, and sexual liberation were some of the main themes. There were many takers of Mahatma Gandhi’s ideals of non-violence and civil disobedience. Much of the liberal modern environment on the campuses of the leading universities in Europe and America is a legacy of the 1968 movement.

In 1968 too the common narrative was the violent repression of students by the security forces, something that seen replayed on the streets of Delhi. That year, Germans students were protesting against the authoritarianism of the West German government, and poor living conditions of the students. In capitalist West Germany, the student stir marked the radicalisation of students inspired by Left ideology. Not far, in Prague, students protested against the communist regime demanding freedom of speech and assembly, which subsequently lead to suppression in the autumn by the Soviet army.

In Paris, students rejected the conformism of de Gaulle’s bureaucratic state, protested against capitalism, American imperialism, consumerism, traditional institutions, values and order. Brutal police repression only led to the active support of the trade union confederations to the students — they called for “sympathy strikes” and involved nearly one-fifth of the population of France. Poets and writers provided intellectual stimulus to the movement — Tariq Ali, Dany Cohn-Bendit, Allen Ginsberg, Jean-Paul Sartre — succeeded in forcing necessary change towards betterment in the working conditions of the toiling masses.

In European countries, of late, it has been students’ movement that led to a more egalitarian society: movements against gender discrimination, racism, anti-war, for nuclear disarmament, clean environment, gay rights and host of other social-political issues. In Germany, for instance, the most popular students’ movements in the last decade or so have been against nuclear power — which is the antithesis of Green — and the rise of neo-Nazi groups.

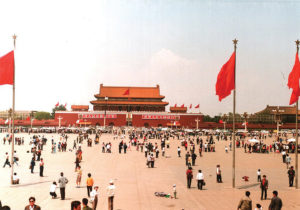

Across the world, students have taken on powerful dictatorial regimes. Thirty years ago, young protesters had gathered at Tiananmen Square in Beijing demanding individual rights and freedom, criticising Chinese economic policy. They were suppressed using tanks, dozens were massacred.

In Hong Kong, a former British colony now governed by China under its “one country, two systems” policy, citizens are given far greater civil liberties, a free press, a robust legal system compared to mainland China. The student protests triggered by the introduction of the Fugitive Offenders Amendment Bill, that allows the extradition of local criminal fugitives even to countries without an extradition treaty, has lasted for months together. The students are particularly wary of misuse of this provision in mainland China and Taiwan, and is seen as an assault on civil liberties by the government. The student stir has been going on unabated for months with more than 3,000 students having been arrested, some of them minors.

History has a clear message, and many examples: Students can be the harbinger of positive change. They will prevail sooner rather than later.