In the US, the authorities feel compelled to investigate and even apologise for an assault on mediapersons. Here, such complaints go nowhere

After a black man named George Floyd, 46, was killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis on May 25, thousands of Americans poured into the streets to protest against racial injustice. The protests spread to more than 75 cities across the United States, inviting a crackdown by the police and the National Guard that has killed at least six people so far and led to the arrests of over 10,000.

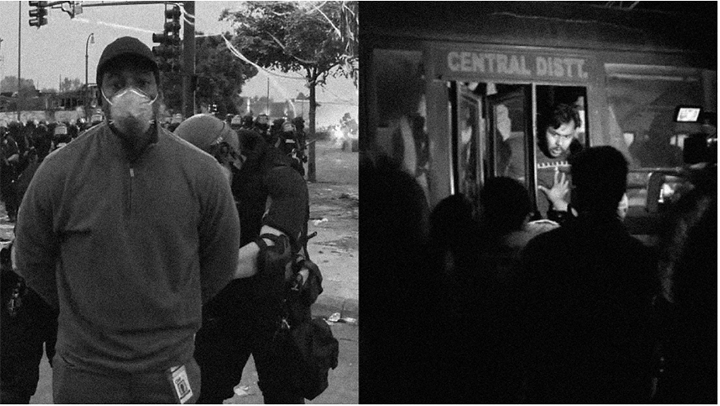

On the third day of the protests, Omar Jimenez, a CNN reporter, was arrested with his team while covering the unrest in Minneapolis. Jimenez was handcuffed on live TV by police officers, despite repeated pleas that he was from the media. He and his team were released an hour later once they were “confirmed” to be mediapersons.

The US Press Freedom Tracker has recorded over 300 press freedom violations since the protests began in the country. According to the Intercept, the police are being held responsible for more than 80 percent of these attacks, with the protesters accounting for the rest.

Besides Jimenez, Christopher Mathias, a senior reporter with HuffPost, was detained while covering the protests in New York on May 30. A Canadian journalist was arrested in New York on June 3, and similar instances were reported in Santa Monica, Oakland, Nebraska and Iowa. In Minneapolis, a journalist was permanently blinded in one eye after taking a rubber bullet to the face.

The state of journalists in the world’s oldest democracy is not much different from that in the world’s largest democracy. A report released on March 9 by the Committee Against Assault of Journalists, a collective of independent media and civil society groups, recorded 32 instances of assaults on journalists in Delhi alone between December 2019 and February 2020.

These attacks — by police, protesters and rioters — happened while the journalists were covering the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the proposed National Register of Citizens. Journalists in Delhi faced a more brutal wave of violence while covering the communal violence in February.

Four months later, watching the attacks on journalists in the United States from India prompts a realisation: that the responses of the two countries to these attacks have been very different.

Earlier this week, Tim Walz, the governor of Minnesota, personally apologised to Omar Jimenez for his and his team’s arrest on May 29.

“Thank you for the professionalism, thank you for understanding, and I’m deeply sorry,” Walz told the journalist, according to CNN. “And you can know that we’ve made other mistakes on this as far as making sure that you have access. But protocols and everything else, as we’re learning, have to change because we have to create the space for you to tell the story.”

The same day, Walz extended his apology to all members of the media who had been detained: “I want to once again extend my deepest apologies, to the journalists who were once again in the middle of this situation who were inadvertently, but nevertheless, detained – to them personally and to the news organisations and to journalists everywhere.”

The First Amendment of the US constitution, which protects press freedom, among other things, is dear to Americans. On June 3, the American Civil Liberties Union said it would file a class action lawsuit to stop “unconstitutional conduct targeting journalists” in Minnesota and other American states. “We are facing a full-scale assault on the First Amendment freedom of the press,” ACLU’s Brian Hauss said in a statement.”We will not let these official abuses go unanswered.

One attack on journalists in Washington DC has led to wider ramifications. On June 1, an Australian reporter and a cameraperson were beaten by police officers while covering a protest in the American capital. The next day, Australian prime minister Scott Morrison asked Arthur Sinodinos, Australian’s ambassador to the US, to investigate the matter. With the matter going international, the police have also opened an investigation into the assault.

In India, there has been no condemnation, or so much as a strong statement by the Narendra Modi government at the Centre or the Arvind Kejriwal government in Delhi. It is worth remembering that the governing Bharatiya Janata Party issued a condemnation when the pro-government Republic TV editor Arnab Goswami was allegedly attacked in Mumbai in April. Not just the party, even the information and broadcasting minister Prakash Javadekar condemned it.

The Delhi police, accused of siding with Hindu rioters against Muslims during the communal violence early this year, never even promised a police investigation into the attacks on journalists between December and February. In a February report on journalists facing attacks during the riots, the Print mentioned that when they reached out to the Delhi police’s PRO for a comment, he “maintained that he didn’t have any information on the attack on journalists during the riots”.

In this respect, the American press has the luxury of a response. After a radio journalist was hit by a rubber bullet in Long Beach, California, the city’s police chief acknowledged the incident, said he would investigate it and stated that he did not want “anyone from the media to get hurt”. In Louisville, where two journalists were hit with pepper balls by the police, a spokeswoman for the police said it was trying to identify the officer, adding: “Targeting the media is not our intention.”

In India, journalists who deal with the police regularly are well aware that their complaints about assault would go nowhere. I have experienced this first hand. In January, while reporting on an anti-CAA protest outside the Delhi police’s headquarters at ITO, a police officer jabbed me in the throat. It happened while I was recording a video of some of the protesters being dragged away. The police were in a foul mood that evening and they had briefly detained a colleague of mine a few hours earlier.

When I confronted the police officer about the attack, there was a stream of the choicest abuses. I approached a more reasonable officer, who contemptuously asked whether I had any evidence. I did have a video but it did not show the officer, so I understood what he meant. Even today, I have a photo of the rotund fellow who struck my throat on my phone but I’m not naive to think that it can be used to investigate that officer. That is out of the question.

This week, the Caravan reported on a poor police investigation into the murder of a former journalist in Punjab. In Kerala, the police are accused of destroying evidence in a high-profile case involving the death of a journalist. In Karnataka, three years after the journalist Gauri Lankesh’s murder, the SIT is yet to arrest all the accused.

The context is definitely not in India’s favour. It is right to point out that American democracy has matured over two centuries and has an array of relatively more reliable institutions than India does. Regardless, both countries face similar problems: besides targeting minorities, the police in both countries attack journalists without a second thought. But in terms of response, the apology by the governor of Minnesota, the investigation by the police, and the lawsuit by ACLU show the American government, police and civil society take the safety of their journalists more seriously.

www.newslaundry.com