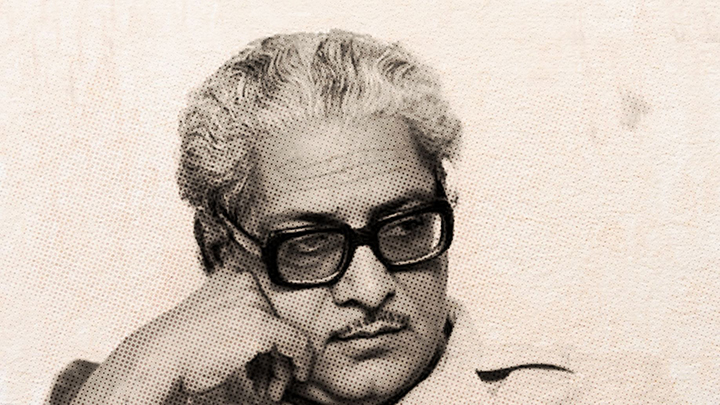

Basu Chatterjee’s legacy is the endearing depiction of middle-class life shorn of melodrama

Urban India’s middle-class young man of the 1970s wasn’t always a brooding figure; he wasn’t always angry. And he wasn’t always weighed down by questions of alienation and existence. He could struggle, yet walk with a purposeful gait. His anxieties could be as immediate as office politics; he could be a fumbling bundle of nerves in his romantic pursuits. And, after all, he took the bus or rode on his Lambretta to go back home. The centrality of his domestic concern gave a sense of order to the world around.

That was what Basu Chatterjee, fondly called Basuda, brought to the Hindi film screen of the Seventies with a light touch. He deftly placed a struggling young man as an everyday antidote to the growing appeal of the “angry young man” genre of Hindi mainstream cinema. In many ways, Amol Palekar of Rajnigandha (1974), Chhoti Si Baat (1976), Chitchor (1976), and Baaton Baaton Mein (1979) was that man. He offered the prospect of a gentle detour from the angst-driven regular course of mainstream Hindi films.

But Basu Chatterjee’s greater achievement was that he let Palekar do that within the mainstream frame.

Along with Hrishikesh Mukherjee, it was Basuda who found the middle ground of blending the entertainment conventions in Hindi films with slices of urban middle-class life. His belief in his approach was so firm that he stuck to it even when he directed Amitabh Bachchan — then the reigning deity of the angry young man genre — in Manzil (1979).

Despite a contrived plot, Bachchan had no room for larger-than-life histrionics in the film. The desperation of Ajay Chandra, the character he played, to get rich was tamed by the middle-class situations revolving around a struggle to set right his galvanometer repair venture. The film, however, wasn’t one of Basuda’s more memorable ones and is remembered more for its song Rimjhim Gire Saawan. The picturisation of the female version of the song showed glimpses of Basuda’s visual sense in portraying songs on the screen. In one of the more imaginatively shot rain songs in the Hindi film history, Basuda gave Mumbai (then Bombay) a lyrical encounter with Monsoon onscreen.

Unlike the male version of the song, the version with Lata’s voice is a background score and for its time, as well as now, it gave a different effect to the aimless wanderings in the rain that played out on the screen. With all the time in the world, Bachchan, in a borrowed grey suit, and Moushumi Chatterjee, barefoot and drenched in a printed green sari, rambled through the rain-washed streets, dotted with a few black and yellow Premier Padminis, and even crossed the Oval Maidan. The lyrical topography of their wanderings on a rainy day makes one now yearn to reclaim urban spaces that are all but invisible in bigger cities.

There were other instances where Basuda realised the impact of a background music score on a sequence of scenes. He chose not to fall for the contrivance of lip-synching. Two memorable numbers come to mind from Chhoti Si Baat — Na Jaane Kyun Hota Hai Ye and Ye Din Kya Aaye — where the background music played against scenes that pushed forward the relationship between Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha, with Asrani as a comic presence.

Three years later, the title song of Baaton Baaton Mein, a romantic comedy woven around a Mumbai-based working-class Christian family, was again a background score. It pushed forward the plot by covering the courtship between Tony (played by Amol Palekar) and Nancy (played by Tina Munim).

Even earlier, in Rajnigandha, Vidya Sinha’s dilemma was expressed through a background number during a taxi journey. Kai Baar Yun Bhi Dekha Hai, rendered by Mukesh, captured the key conflict in the film’s plot without the contrivance of lip-synching.

Basuda’s earlier days of apprenticeship, as an assistant director on Teesri Kasam (1966) and Saraswatichandra (1968), perhaps made him aware of the significance of music in the grammar of mainstream filmmaking in India. He was alive to the need for music in his films while crafting the manner in which to use it.

Another early influence that stayed with him was that of literary work in his craft, along with the imprint of cinema in different languages, both foreign and Indian. Basuda’s first film, Saara Akash (1969), was a rather serious film which showed his penchant for literary inspiration. Based on the first part of Hindi writer Rajendra Yadav’s debut novel (originally published in 1951 as Pret Bolte Hain), the film explored the middle-class tensions and domestic complexities of a family in small-town India.

Basuda’s fascination for regional literature as a source for his narratives was also evident in his career as a director of television shows. In 1985, his series Darpan for Doordarshan was based on stories chosen from the literature of different languages.

His repertoire of films in the following decades did not have the same degree of resonance with the audience, a large section of which was the new generation hooked to the video era, while commercial filmmaking was having a major narrative shift. Except for a few films like Chameli Ki Shaadi (1986) — a quirky take on caste and wrestling as a way of life — his films during this period did not leave a mark beyond his loyal fan base.

However, he compensated for it by directing popular TV shows like Rajani (1985). The series was a reminder of Basuda’s grasp on the urban middle-class audience, though it did something he hadn’t done before: it had an activist narrative revolving around a woman fighting for consumer rights and civic issues. Basuda had generally refrained from didactic stuff until then. He followed Rajani with the courtroom drama Ek Ruka Hua Faisla (1986).

However, it was Kakaji Kahin (1988) that did his satirical side some justice, with Om Puri playing a small-time politician with hilarious authenticity. His impressive body of work for Doordarshan was capped by the unassuming detective series Byomkesh Bakshi (1993 and 1997), a series that still retains its admirers for weaving detective tales with narrative simplicity while reflecting the quaint charm of old-world Kolkata.

In some ways, Basu Chatterjee did find ways to defy the date of his work being defined by an era. That was probably a tribute to his prolific output and creative persistence. Still, he can’t beat the memory that he today evokes in admirers: a memory of the decade where he found the struggling young man in urban middle-class homes. The way he dealt with him and others around him in mainstream Hindi cinema will be his enduring legacy. He can sometimes even make you feel that you should have lived in the unhurried Seventies.