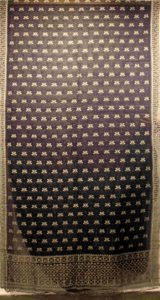

This latest exhibition at India International Centre, in collaboration with Art Konsult, presents a unique look of the jamdani sarees representing the quality and skill of artisane from pre-British Raj era

From the late 19th century, some from an even earlier period, to some rare pieces produced by the East India Company – here is an exhibition that transports you back to the old world where the art of weaving was revered and celebrated.

Displaying museum quality Dhakai Jamdani sarees from the collection of Siddhartha Tagore, Art Konsult in collaboration with India International Centre presents ‘A Glorious Past and a Shining Future for Dhakai Jamdani’ curated by Puneet Kaushik and Rema Kumar.

Jamdani was originally called Dhakai, after the city of Dhaka from East Bengal, now Bangladesh, where it was exclusively hand-woven for centuries. In its truest form, Jamdani denotes muslin, a fine cotton fabric, with geometric or floral motifs woven on handlooms by skilled weavers from Rupganj, Narayanganj, and Sonargaon around Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka.

Muslin was deemed worthy of clothing statues of goddesses in ancient Greece, countless emperors from distant lands, and generations of local Mughal royalty. So enamoured with this masterfully finished fabric, they affectionately named it in Persian after the floral patterns found in the Dhakai textile, ‘Jam’ meaning flower and ‘Dani’ meaning vase or container, offering its weavers extensive patronage.

Due to the laborious and painstakingly precise methodology involved, only aristocrats and royal families were able to afford such luxuries.

“Though the looms used were simple, the pattern detailing was labour intensive and apart from time, it required the dexterous and delicate touch of a master weaver to make. Though weaving was done by Muslims, most of the spinning was done by Hindu women. The weaving techniques were passed down generations orally through songs making each weaving cluster exclusive repositories of favourite motifs,” reads the curator note.

Remarkable precision was required in each of the 16 steps, as it was carried out by a different village around Dhaka, which was then part of Bengal – some in what is now Bangladesh, some in what is now the Indian state of West Bengal. It was a true community effort, involving the young and old, men and women.

The decline of the Bengali jamdani and muslin began when the Indian subcontinent came under the British Raj. It eventually lost out to the cheaper mill-produced European textiles such as Manchester cotton. By the early 20th Century, Dhaka muslin quietly vanished from every corner of the globe, with the only surviving examples stashed safely in valuable private collections and museums.

However, in 2013, UNESCO declared the traditional art of weaving Jamdani an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”. In 2016, Bangladesh declared the Jamdani as its first GI product. The Jamdani Festival organised by the National Crafts Council of Bangladesh and the Bengal Foundation in 2019 helped revive interest in this weave and efforts are on to restore the Jamdani to its original excellence and bring back the glory of this legendary textile tradition.

The exhibition is on display at India International Centre till October 4