Despite the efforts of several suicide helplines, over 1,00,000 people commit suicide in India every year. The stigma around mental distress in India can be blamed for these staggering figures

“The words ‘I was suicidal’ still taste a little strange in my mouth,” says 22-year-old Anisha*. “It was a struggle to wake up every day, and nothing felt worth it. Even to this day, if you ask me to pinpoint the reason why I wanted to kill myself consistently for two years, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. But I did. And the fact that I am not able to vocalise my trauma, does not make it any less real.”

Suicide prevention is yet to be taken seriously as a legitimate concern in India. And while the numbers show slow declines in the suicide rates in Delhi, a lot of these statistics are likely misinformed. Data released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) in 2015 showed that over 1,00,000 people commit suicide in India every year. A study done on suicide death rates from 1990-2016, which was published in the Lancet Public Health medical journal, estimated the suicide rates for males and females based on various different sources. And as of 2018, India accounts for a significant fraction of the world’s suicides.

Vikramsinh Pawar, Senior Program Coordinator of Connecting NGO, says, “We get more male callers than female callers, however, the number of attempted suicide cases is higher with women.” Connecting NGO runs a helpline that receives at least 8-10 calls every day. “There is still a stigma around suicide in India, especially with people coming from lower income groups,” he says. They have trained volunteers manning the helplines and provide a safe and non-judgemental ‘listening space’ for the callers. “When you start attempting to provide a solution to their problem, a part of the communication gets blocked. More often than not the callers are aware of the solutions to their problems but they lack the courage. We train our volunteers to listen and provide an objective mirror image of their issues — creating a safe emotional space for them to vent,” elucidates Pawar.

Connecting also receives calls from family members or friends of those who attempted or committed suicide. Pawar explains that the age group of callers ranges from 14 to 50 years and the circumstances are often ambiguous. Family members who feel responsible for the suicides suffer from post-traumatic stress, those contemplating suicide just want someone to empathise. Callers dealing with different kinds of personal crises will call just for a non-judgemental ear. “We have several helplines and organisations that deal with suicide prevention, but the government has done little to draw to attention to this problem. We have the infrastructure, but it is not being utilised to its fullest capacity. If the government focuses a little more on suicide prevention, all the work that these NGOs do might actually be legitimised,” adds Pawar. “We have been doing this work for donkey’s years, but the government I feel is not active enough in this area.”

Sanjay*, 30, suffers from anxiety attacks and clinical depression, and has been taking medication for a while now. “On my good days, I know that I don’t want to die. I think that most people who have suicidal tendencies know subconsciously what would happen if they actually followed through with those unhealthy thoughts. But on the bad days, it really does feel like, maybe dying wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen,” he says. “I speak of it this casually because I’ve been dealing with this part of my personality for a few years now, but it’s terrifying for those who are experiencing these thoughts for the first time. I certainly was,” he recollects.

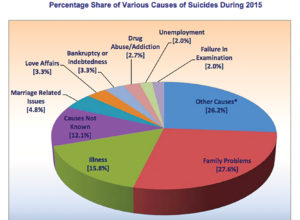

The leading causes for suicides are relationship issues (marital, familial and friendships), employment problems, repressed mental illnesses, and problems related to sexuality. A mirror image of all the problems we are dealing with as a country reflected on a very personal level, in the lives of common people. Paying attention to these stories and perspectives lends a closer look into how to identify and tackle the epidemic of mental illnesses and suicides in the country.

Preeti*, 22, had been clinically depressed for many years before she sought help. “I remember crying myself to sleep, thinking about how my friends did not care about me. I know now that they did, and still do. But at the time, there really wasn’t anything I could say to myself to feel better. I realised that I needed to get my thoughts in order and really address the problem when I started to get really violent thoughts about the people closest to me. It made me very uncomfortable,” says Preeti. She was prone to self-harm as well. She recalls spending long periods of time in the kitchen in the middle of the night just holding the knife and contemplating whether or not to use it on herself. “Later on, I would hide the sharp objects away whenever I was in a bad space of mind. Panic attacks were frequent,” she says ruefully.

“We spend at least 35-40 minutes on every call, and sometimes even four hours at a stretch to talk to the callers and help them navigate their respective difficult situations,” says Pawar. “It also takes a significant toll on our volunteers.” Given the number of individuals with mental health issues and the sheer number of people tackling suicidal thoughts every day, it stands to reason that the steps taken for prevention would be way more popular and more widely accepted. Sadly, though, that is not the case. Suicide prevention helplines and other such organisations can only help when the help is asked for, the wait is only for us to destigmatise the issue of self-harm and suicide and encourage conversations around it.