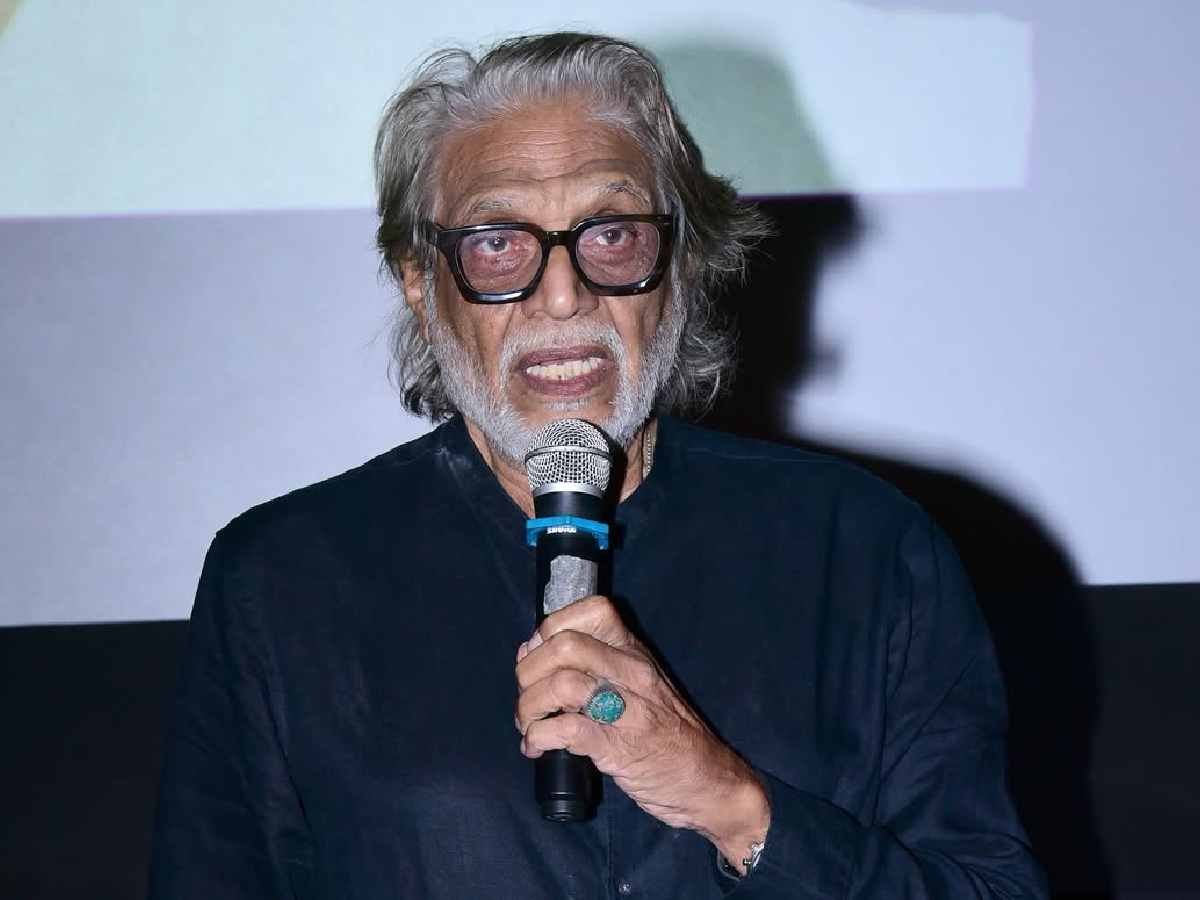

Filmmaker, painter, designer, author, and cultural custodian Muzaffar Ali believes cinema, at its best, merges poetry, music, and history into living experience.

In an interview with Patriot, Ali spoke about the magic of film, the craft behind it, and why some stories cannot be recreated.

A labour of love

“Without pain, there is no art. A person who doesn’t feel pain is not an artist,” Ali said. “A child is not born in a day, it takes nine months. In the same way, whatever concept comes to the mind, it slowly comes to the fore.”

Ali recalls the work that went into Umrao Jaan, from recreating Lucknow’s grandeur to capturing the nuances of tawaif culture. “We shot it for a year in two seasons in 1980, extensively in Lucknow, Faizabad, and in Mehboob Studio, Mumbai, where we recreated a kotha with original artefacts. Umrao Jaan should be seen as a love letter to Lucknow. The re-release was a reassurance that the film is alive.”

Growing up in the city, he saw the film as authentically dealing with Awadh culture, its angst, and the trials of women. “My challenge was to present Awadh the way Ray was presenting his Bengal. There was nobody to present Awadh in that sense, so I took it upon myself to present a truthful slice of reality.”

Rekha: A miracle in cinema

Casting Rekha as Umrao Jaan, Ali says, was “one of the greatest miracles of my life. If there is no Rekha in it, then there is nothing. If there is no Khayyam, then there is nothing. If there is no Shehryar, then there is nothing.”

He wanted her seen not just as glamorous but as a human being. “Previously, her roles in Suhaag and Mukaddar Ka Sikandar were traditional courtesans. Here, I wanted people to look at her as vulnerable. All the work—dialogues, poetry, clothes, and music—was culminating on one level, and her immersing herself into the character on another.”

The ensemble cast, from Naseeruddin Shah to Shaukat Kaifi, Bharat Bhushan, and Dina Pathak, added authenticity. “They were all my first choices. I wanted the relationships to be gentle, natural as they could have been in those days. These were understated method actors. They brought out the character in its true sense.”

Music and poetry

The soundtrack of Umrao Jaan, composed by Khayyam with lyrics by Shahryar, remains central. “You have to see the whole trajectory of poetry in her life, as an evolution of a character, from optimism to disillusionment to total abandonment. Songs like Dil Cheez Kya Hai and In Aankhon Ki Masti encapsulate the essence of her journey,” Ali said.

Urdu, poetry, and music remain the backbone of his vision. “Urdu is a language of love and interconnectedness. When used authentically in cinema, it touches the soul. Any attempt to exaggerate it only dilutes its power. Poetry takes you to such a place… till you don’t come down to your bottom, you won’t see anything.”

For Ali, Awadh is not just a location but a cultural memory. “It had to be my experience, what I lived through, what the walls had spoken to me, what clothes and festivals meant to me.”

Creation over commerce

Ali has consistently chosen depth over speed. “You can do business according to money, according to hours. But creation is going into depth. Until you drown in it, you can’t get anything. When you start a work with the intention of love and humanity, then something else comes out of it.”

Also Read: Sudipto Sen on cinema, conflict and controversy

He says his films are painted before they are shot. “I deliberate on light, texture, and frame before I invite movement. I choreograph cinema like an orchestral composition—with rhythm, shade, and detail. That’s where the poetry begins.”

The legacy of Umrao Jaan

The restored 4K release by the National Film Archive of India and the National Film Development Corporation ensures the film’s survival. “Whatever has gone in the public domain, on the net and the cloud, will stay. Otherwise, physical films will just evaporate. The government’s awakening to this is timely and important,” Ali said.

He also released a limited-edition coffee table book with 250 archival photographs from the set.

Reflecting on the film’s resonance, he said, “I realised that it was going to get under the skin of people. When this film becomes a part of a person’s breath, when it becomes a part of his heartbeat, then I think it is a great achievement.”

Cities and inspiration

Every city, Ali says, shapes the artist. “Aligarh gave me poetry. If I had not gone to Aligarh, I would not have become anything. My training has been to get something from the heartbeats of the people of the city.”

Nature and painting remain sources of inspiration. “Understanding nature, respecting nature, that is a great inspiration. All colours are connected with feelings. And all feelings are connected with nature.”

Ali’s next project, Zooni, is being completed in collaboration with his son, filmmaker Shaad Ali. “It’s like a dialogue between father and son with a past. I also have a few scripts ready to start soon.”

In an era of rapid cinema production, Ali remains a patient custodian of art. “I’ve never needed to be in the marketplace. My work speaks through other forms—textiles, poetry, festivals. Art must serve a higher purpose—to bring peace.”