The Indian voter is always ahead of politicians, ‘teaching them a lesson or two when necessary’, says this timely book by Prannoy Roy and Dorab R Sopariwala

The timing is impeccable. The Verdict is out just two months before the 2019 Lok Sabha polls. Away from the din of campaign rallies and the cacophony of TV studies, this book by India’s first high profile psephologist does a level-headed analysis of many patterns and trends in voting. A weekend spent reading this book is more enlightening than hours of scrolling through social media or watching debates — it gives you a context.

It’s also a light read, with the most reader-friendly tables possible, not complex charts or graphs. Not surprising, considering Prannoy Roy is “renowned for his knack of demystifying electoral politics,” as the jacket says.

For those who love numbers, this book is pure delight. It tells you that the country has seen 392 elections, out of which 376 were State Assembly and 16 Lok Sabha polls. Women’s turnout is now 66%, the rise of 19% since 1962 much higher than the rise of men’s turnout by 5%. The landslide rate in big and medium-sized rates during Lok Sabha elections is 77% (landslides are defined as elections in which the seats won by the winning party alliance in a state is twice that of the one coming second).

The book tells us that Muslim representation has remained static over the years, with 25-35 MPs on average in the Lower House. The phenomenon is explained at some length, one rational explanation being that the community is spread geographically, and not concentrated in any constituency, unlike Sikhs in Punjab, also a minority community. “While more Muslim candidates are now being nominated by various parties, with the notable exception of the BJP, they are not winning in equal proportion. Muslim candidates do not fare well in elections and their winning strike-rate has been falling rapidly. From 50 per cent of contesting candidates going on to win their seats in the first phase (1952-1977), when parties had relatively few Muslim candidates, the winning ratio has fallen dramatically to only 17 per cent in the latest period (2002-2019)”, says the book.

Some of the information that is not part of common wisdom but is pointed out in the book is:

- A divided Opposition enables the largest party to sweep the polls with even a small percentage of votes

- While in the West, there is pro-incumbency, where the incumbent politician or party has a high chance of being voted back to power, in India we have high anti-incumbency. However, this uniquely Indian phenomenon, fuelled by angry voters, is on the decline.

- In a remarkably high 93% of the time, the party that wins the State Assembly election also wins the largest number of seats in that state in the Lok Sabha elections (if held within a year).

- Since the turn of the century, for victory in an election, dividing the Opposition vote is almost as important as winning a highly popular vote

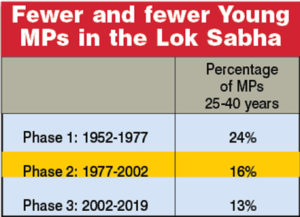

- Only 15% of MPs are in the age-group 25-40. The average age of MPs has gone up from 47 to 60 years in the present time.

- Mid-term by-elections are often treated by some voters as an opportunity to ‘let off some steam’, and to send a wake-up call to a party they would normally support.

- There is a higher voter participation in panchayat and municipal elections than in Lok Sabha elections.

A chunk of the book — 130 pages, about half — is devoted to How to Forecast India’s Elections and How to Make Your Own Forecasts. Though there may be good money in successful predictions, especially in opinion/exit polls broadcast over mass media, most voters are only interested in the actual results, and have only a passing interest in the forecasts that may or may not come true. Of course, the pollsters who are into this business will get a lot of gyan from these chapters. This reviewer would draw a parallel between opinion/exit polls and cricket, the other national obsession, where only a small percentage of people indulge in betting, whereas everyone and his aunt are all agog about the winner of the game. A big difference between opinion polls and cricket is that a substantial part of the fun in cricket is the excitement of the game itself, whereas public attitude towards the elections is a weary desire to see them done and dusted. The only excitement the common voters experience is the sighting of celebrities, whether film stars or glamorous politicians.

Be that as it may, the book tells us there are likely to be 100 polls of different types and sizes in the runup to the current elections. The Election Commission, in fact, banned the publication and broadcast of exit polls till half an hour after the last phase of polling in the last round of Assembly elections. But the ban applies to regular media outfits. What about social media? The authors warn readers about the unscientific nature of social media polls, where the sample is never random, mostly because people are supposed to volunteer to send their answers instead of being accosted at street corners or questioned at home. But will today’s netizens pay heed? People read and forward almost automatically, especially to WhatsApp groups, a practice that is mindless and amounts to rumour-mongering.

The book delves into the EVM controversy and comes out clearly in their favour. Since they are standalone units, goes the argument, they can neither be hacked nor ‘pre-programmed’, except at the manufacturing stage. In fact, the technology solved big problems like ‘booth capturing’, which only the older generation remembers now. Also, they are more environment-friendly, “having saved almost a quarter of a million trees from being cut down”.

There has been some hype that this forthcoming election is the most crucial for India’s future. However, when you read about 1977, you realise that this was a much more crucial vote, the one that brought India back on the path of democracy after the dark Emergency years. And though the book doesn’t say so, the 2014 elections were much more tense, because for a whole two years in the runup, there was an unravelling of scams and a paralysis of Parliament by the BJP. The stalemate and the suspense had become unbearable for the nation, which was waiting with baited breath for the two major political parties to settle the issue of who had a right to rule for the next five years.

Moreover, in 2014, the BJP was expected to be radically different once in power, considering its swadeshi bluster, promise of uniform civil code and abolition of Section 370. Since then, we have seen these promises being belied, the Congress adopt soft Hindutva, the BJP too propping up its own crony capitalists and the regional parties gaining major bargaining power.

So, would any ‘new’ Lok Sabha be radically different from the last?