This exhibition is a commentary on the socio-political situation of the country at a time when counter-truths prevail, inviting frequent violence

“Truth was supposed to hit home before a lie.” Reads the bright red text on the wall leading to an exhibition hall. In the era of post-truth, where rampant fake news is spiralling out of control, the quoted remark couldn’t get any more apt.

Growing more audacious by the day, Indians do not hesitate to take law into their own hands on grounds of religion — the recent mob lynching at Bulandshahr testifies to that. An alleged incident of cow slaughter claimed the lives of an inspector and a civilian, when a clash between the mob and the police escalated into a riot on Monday.

Making a commentary on this socio-political status of the nation, artist Atul Bhalla raises questions on the current religious intolerance through art. Showcasing a combination of new and old body of works — including ¬archival prints, Diasecs and installation — his works are on display at the exhibition titled ‘Anhedonic Dehiscence’.

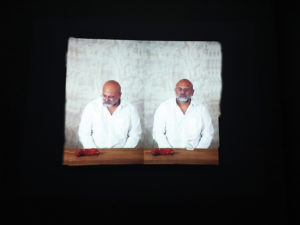

Stepping into the gallery, one recurring element that stands out the most is a slab of raw meat. Through a video installation, Bhalla stares right back at the viewers from the screen that almost takes up an entire wall at the gallery. In this series of self-portrait, the artist is sitting with just a slab of meat and a glass of water. As the video proceeds, he keeps moving the glass around, careful to not touch the meat. After a while he looks at the meat and once again stares back directly at the viewers.

Bhalla consciously featured meat to catch the attention of the audience. “It explores the politics of what we can eat today and what we cannot. Not moving the meat, I avoid something right there under my nose, and I keep looking elsewhere. What has to be addressed, we fail to discuss. I want to bring it to the table, something we are not talking about. As if in a conversation, we keep talking about something else but do not address the real issue.

I am implicating myself through this work, to be vulnerable and equally responsible,” he explains.

Not just the video, meat turns out to be a central element in several other still photos as well. In the context of the present communal violence, Bhalla created another notable series ‘Objects of Fictitious Togetherness’, through which he explores the elusive historical truth that can possibly never be known.

This idea triggered from Rajmohan Gandhi’s book ‘Punjab’, which talks about 1930s pre-Partition Punjab, where separate water arrangements were made for Hindus and Muslims. “Reminiscent of such untouchability and religious practises are still prevalent in most of India, at least unofficially and maybe more so now given the rise of the Hindu right.”

The book mentions about a ceremony held by the Unionist Party in early 1900s where they got Hindus and Muslims to drink water together from the same glass — the idea was to drink their ‘jhhootha’. This incident struck a chord with Bhalla and he took off to examining the implications of this.

“Was the water local? Who drank first: The Hindu or the Muslim? Whose glass, was it? Where did it go after?” An attempt to find answers to these questions and locating that elusive glass took him to his ancestral village, Sri Hargobindpur in Gurdaspur district of Punjab.

Going around his village, he went out hunting for old glasses used by people and old utensil shops where the villagers might have changed it for new ones. In the end, he managed to collect 163 brass glasses of varying sizes — on display at the exhibition — hoping that one of them would be that elusive glass of ‘fictitious togetherness’.

Breaking down the title ‘Anhedonic Dehiscence’, Anhedonia refers to a psychological condition where there is a lack of pleasure. Dehisce means rupture and eruption of a wound from the same suture. “I combined these two medical terms into a social metaphor of the times we live in today. Even an eruption or a will to shout is pointless. The truth is the dehiscence,” explains Bhalla.

Some of photos of landscapes on display are continuously ruptured with crooked lines running across the images. “They are devoid of pleasure –anhedonic alienation and dissociation. Perfect landscapes breakaway and slivers of wounds tear open forcing the viewer to be uncomfortable. The images are ruptured as if it’s a dehisced wound. It’s about a kind of impotence, about not being able to deal with our socio-political times.”

This series also explores the mayhem of partition and the resulting politics played out by India and Pakistan. A victim of communal violence himself, Bhalla ends the exhibition on a personal note. At the very end of the exhibition is a photograph of a house with a note that reads, ‘They spared me here’. “During the 1984 riots they took one of my friends, who was a Sikh, from outside this house in Patel Nagar, Delhi. They spared me because I did not wear a turban. The guilt continues to live with me,” he says.

Bhalla’s work forces an introspection, a gentle reminder of the reality that is often overlooked. The meat remains as it is, whereas the glass of water is shifted around but never spilled.

The exhibition is on display at Vadehra Art Gallery till January 3.