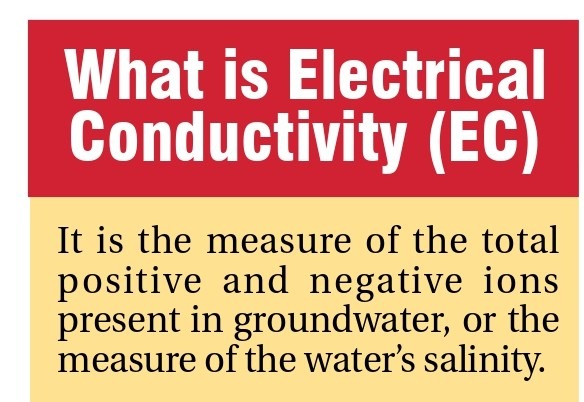

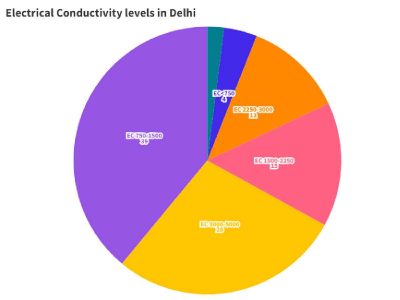

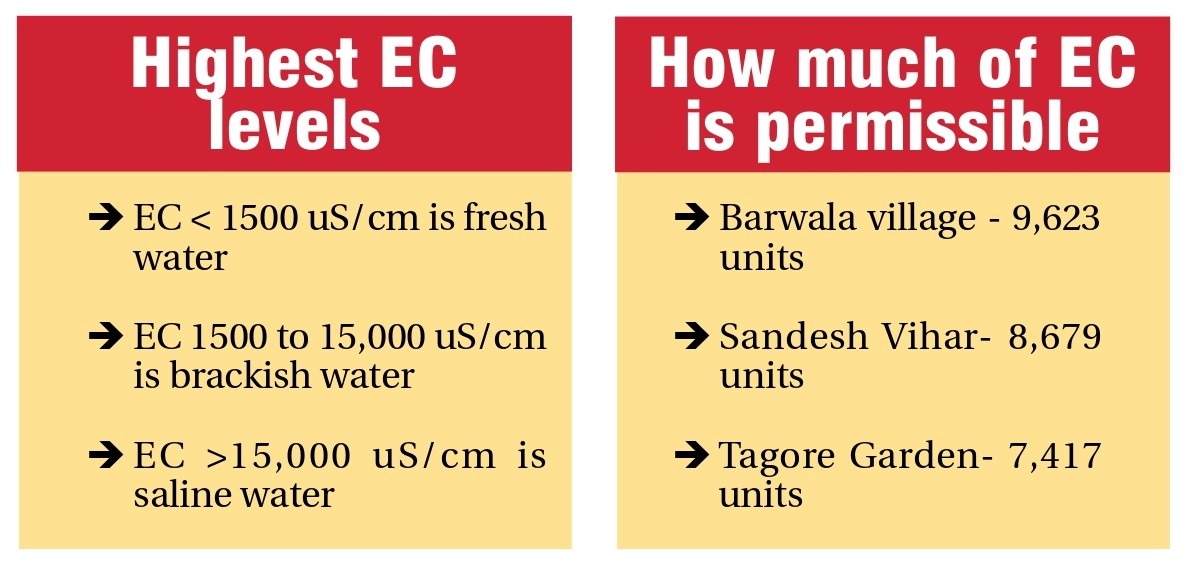

Electrical conductivity is a measure of how well water conducts electricity, with a higher amount of minerals leading to better conductivity. In groundwater, EC between 750 microsiemens per centimetre (µS/cm) and 3,000 µS/cm is classified as “permissible,” while readings over 3,000 µS/cm are often considered “highly saline.”

According to the findings, 25 per cent of randomly collected samples exhibited high salinity, which directly contributed to increased EC levels. The report is based on data from the National Hydrological Survey, 2022–23.

As a result, nearly half of Delhi’s groundwater is now deemed unfit for consumption, primarily due to high salinity and conductivity. This situation has placed Delhi in the unenviable position of having the second-highest groundwater salinity in the country, just behind Rajasthan.

The report also revealed that more than 32 per cent of Delhi’s districts had groundwater with EC levels exceeding 3,000 µS/cm—well beyond the safety threshold. The North, North West, West, and South West districts are the most affected areas.Some of the highest EC levels were recorded in Barwala village, Rohini (9,623 units), Sandesh Vihar, Pitampura (8,679 units), and Tagore Garden, West Delhi (7,417 units). Other affected areas include Auchandi, Shikarpur, Sultanpur Dabas, Najafgarh, and Chhawla.

It’s worth noting that the National Hydrological Survey, 2021-22, indicated that 39.3 per cent of districts in the national capital had EC levels exceeding 3,000 µS/cm.

Barwala Village

The situation in this hamlet, beyond the urban quarters of Rohini, is one of stark contrast between those who have access to water and those who do not. Some residents are connected to the Delhi Jal Board (DJB), the national capital’s premier potable water supplier, while others must rely on submersible pumps to extract groundwater.

Residents forced to use the village’s poor-quality groundwater have experienced multiple health issues, especially stomach ailments, with children being the worst affected. Many are uncertain of the cause but suspect the contaminated groundwater may be to blame. In addition to the poor quality, the water supply has been inconsistent for the past three years, leaving many to yearn for even a drop.

Phool Singh, a 44-year-old homemaker, has spent countless days worrying about whether there would be enough water for her household. “We have started using water tankers and buying drums for household chores and drinking. For the last three years or so, the supply has been erratic. More often than not, even when we receive water through the pipeline, it is dirty and brackish,” she said.

She added that her household had lodged complaints with the concerned authorities, but DJB officials were at a loss. “At first, they thought a burst sewer had contaminated the water supply. They fixed it, but the water remained brackish and dirty. Now, they’ve told me they don’t know what’s wrong,” she said.

This issue is not isolated to Phool Singh’s residence. Shivraj Dabas, a 20-year-old resident, said, “The flow of water has been very erratic, especially in the past couple of years. Initially, it happened once or twice every six months, but now it’s a monthly issue. Even when we get water, it’s not drinkable. We use it only for household chores, and even then, we rely on water tankers since the DJB pump house is nearby.”

An initial survey also revealed that around 99 per cent of Delhi’s groundwater has been depleted.

Sandesh Vihar

Despite being a more affluent area in North West Delhi’s Pitampura, Sandesh Vihar hasn’t escaped the worsening groundwater quality. While residents aren’t as severely affected as those in Barwala, the impact is noticeable in some public spaces. Workers, including security guards and shop owners, often rely on water from pumps, as do several temples in the area.

Most residents have access to DJB’s water supply, but some temples, lacking such connections, use water from their own motors. Unfortunately, this water is brackish and dark-coloured.

“The water has always looked like this. I’ve never had an issue, but it does taste a bit salty sometimes,” said Bharat Kumar (name changed), a security guard.

Also Read: Delhi markets struggle with poor sanitation as authorities fail to act

Some residents mentioned that during the pandemic, they occasionally used groundwater due to disruptions in DJB’s supply. “We used both sources. Most of our house had DJB water, but we also had a submersible pump. We stopped using it after the pandemic because the water became hard,” said Pratibha Sharma.

Najafgarh

Unlike Sandesh Vihar, much of Najafgarh relies on its underground water supply. On June 27, it was reported that the groundwater table in the area had risen by three metres—a significant achievement. However, high electrical conductivity (EC) levels still pose a serious health risk, making waterborne diseases inevitable.

Zeenat Khan, a 26-year-old mother of two, shared how her sons had suffered from recurring stomach aches a couple of years ago. “He used to tell me that the water tasted strange, but I didn’t think much of it. It had always tasted that way. He had already fallen sick a few times before. But one day, the water supply was disrupted, and for a few weeks, we had to use tanker water,” she said.

After switching to tanker water, her son’s pain disappeared almost immediately. “Now, we only use submersible water for daily chores, not for drinking,” she added.

After switching to tanker water, her son’s pain disappeared almost immediately. “Now, we only use submersible water for daily chores, not for drinking,” she added.

A 2013 report by the Department of Geology, Delhi University, found that groundwater near the Najafgarh drain was contaminated with toxic metals like lead and cadmium, both of which can cause cancer. Other harmful substances such as arsenic, nitrate, manganese, and iron were also detected.

What happens with high EC

According to the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), the ideal level of total dissolved solids (TDS) in drinking water should not exceed 500 milligrams per litre (mg/L), which corresponds to an EC of around 750 microsiemens per centimetre. However, in situations where alternative water sources are unavailable, the permissible limit for TDS can be extended to 2,000 mg/L, translating to an EC of 3,000 microsiemens per centimetre.

Despite this allowance, experts warn that water with TDS levels above 2,000 mg/L can lead to serious health risks, particularly kidney-related illnesses. The BIS advises that water with such high TDS levels should only be consumed when absolutely necessary.

Despite this allowance, experts warn that water with TDS levels above 2,000 mg/L can lead to serious health risks, particularly kidney-related illnesses. The BIS advises that water with such high TDS levels should only be consumed when absolutely necessary.