Mohan Chandra experienced the shock of his life upon learning from media reports that Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium (JLNS) in New Delhi is slated for demolition to make way for a proposed 102-acre Sports City. The news hit him hard: he had witnessed the stadium’s construction firsthand during the 1982 Asian Games. The report revived memories of a time when the site was little more than barren land before its transformation into a sporting landmark. Those were the years when he lived in Block 8 on Lodhi Road.

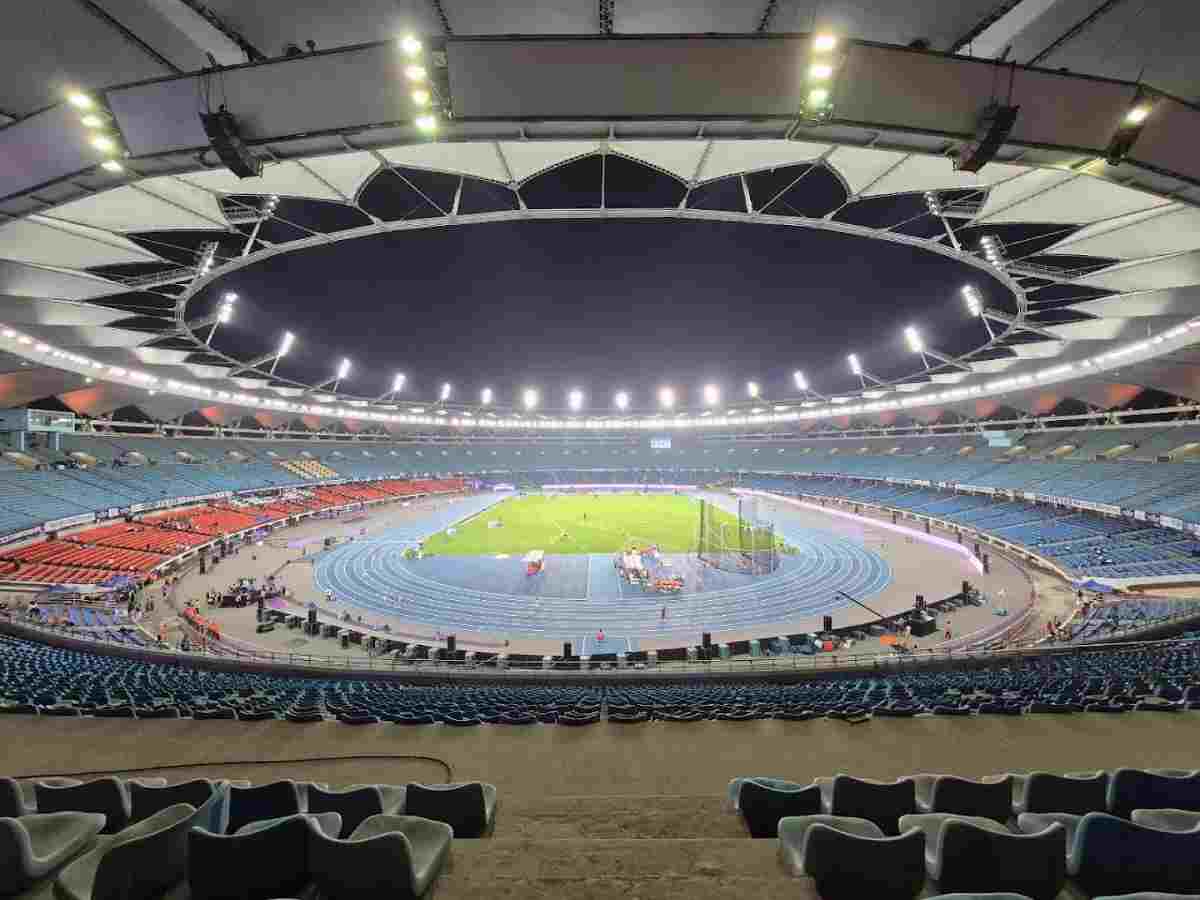

Nestled in the heart of New Delhi, JLNS stands as a monumental chapter in Indian sports history. This 60,000-seat arena has hosted triumphs, controversies and cultural milestones over four decades. From its rushed construction ahead of the Asian Games to its lavish overhaul for the 2010 Commonwealth Games, the stadium transcended its role as a mere venue, becoming a stage for athletic excellence and entertainment spectacles. Now, after 40 years, the curtains appear set to come down on this national landmark.

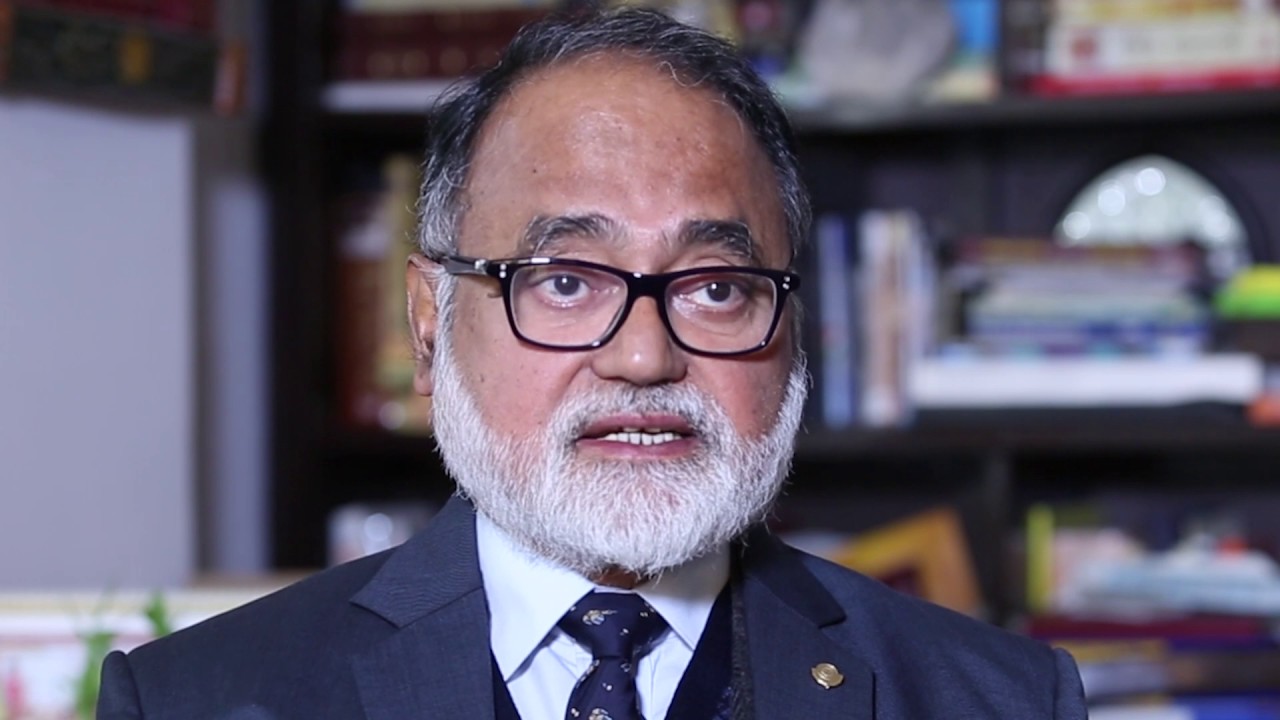

Sumit Dutt Majumdar, an author and former Indian Revenue Service officer, shares a personal anecdote from the stadium’s frantic final days before the Games. “I was tasked by Rajiv Gandhi [then Prime Minister] with overseeing the stadium’s construction as the opening ceremony loomed, with much work still unfinished,” he recalls. “On the big day — November 19, 1982 — I received an urgent call from K.T. Satawala, the Games’ Chief Coordinator, summoning me to his office. He informed me that ‘VICTOR ONE’ — our walkie-talkie code for Rajiv Gandhi — needed me at the Asiad Centre immediately to address critical issues. My face paled as I protested that I’d miss the opening ceremony. But he reminded me of the privilege of Mr Gandhi’s trust in entrusting me with such a massive responsibility. So, I skipped the grand event in the very stadium I toiled around the clock to complete on time.”

The origins

The JLNS story began amid India’s ambitious preparations for the Ninth Asian Games. Construction commenced in 1980 on a 102-acre plot, overseen by the Central Public Works Department (CPWD). Thousands of workers, primarily from Bihar and Odisha, were mobilised to finish the colossal structure in just two years. The initial design emphasised practicality: an oval bowl with tiered concrete seating, a 400-metre synthetic track surrounding a football field, and floodlights for night events. No individual architect claimed sole credit; it was a collaborative effort by CPWD engineers, inspired by FIFA and World Athletics standards. The budget swelled to over Rs 50 crore — a substantial sum at the time — funded largely by the central government.

Milkha Singh’s role

Few know that legendary sprinter Milkha Singh advised the Asiad ’82 Secretariat on technical matters. Majumdar recounts a pivotal moment: “The Indian Football Federation complained that the JLNS football field, encircled by the athletic track, was smaller than standard and needed expansion. With time running out, a high-level meeting was convened. We argued that while slightly undersized, it still met FIFA guidelines. Then Milkha Singh stepped in, explaining that enlarging the field would sharpen the track’s corners, causing disadvantage to sprinters in the 400m and 800m events. His expertise carried the day, and the design remained unchanged.”

Carl Lewis’s presence

In 1989, JLNS hosted one of the greatest athletes of all time: Carl Lewis, who competed in an athletics championship during the peak of his career. He drew massive crowds for the 100m final — his signature event. As the starting gun fired, a stunned silence followed when Lewis placed second to an underdog Austrian runner. For fans, witnessing him compete remained unforgettable. After the race, Lewis spoke informally with a handful of journalists outside the media centre — in an era before constant news cycles and selfies. He later returned to inaugurate a marathon at the venue.

Modern metamorphosis

By the early 2000s, JLNS showed signs of wear — cracked stands, outdated facilities and capacity limitations that fell short of modern safety standards — rendering it unfit for top-tier events. India’s successful bid for the 2010 Commonwealth Games sparked its revival. In 2006, an international design competition was held, won by Hamburg-based GMP Architekten. Their redesign transformed the ageing structure into a modern, sustainable arena, blending Indian architectural motifs with advanced engineering.

Major events

After 1982, JLNS evolved into a vibrant cultural hub beyond sports. Just a year later, on September 21, 1983, it staged cricket’s first day-night match outside Australia — an unofficial India–Pakistan encounter under trial floodlights.

Also Read: Prithiviraj Road: from Tata House to Ambedkar’s abode

Through the 1980s and ’90s, it hosted ODIs against teams such as Australia and South Africa, as well as iconic concerts by Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band, Sting, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman, Youssou N’Dour and Ravi Shankar. Michael Jackson’s scheduled 1993 Dangerous tour stop was cancelled due to his illness.

Infrastructure overhaul

Yet even iconic structures must evolve. Strong indications now suggest that JLNS will be dismantled to make way for a 102-acre Sports City, aligning with India’s aspirations for the 2036 Olympics. The redevelopment promises state-of-the-art facilities but marks the end of an era for a stadium etched into India’s collective memory. Around 35 years ago, a group of students from various African countries studying at Delhi University practised here under the watchful eyes of the great athletic coach Ilyas Babar. One of them told this writer, “You will not find such a grand stadium in all of Africa.” Others echoed the sentiment.