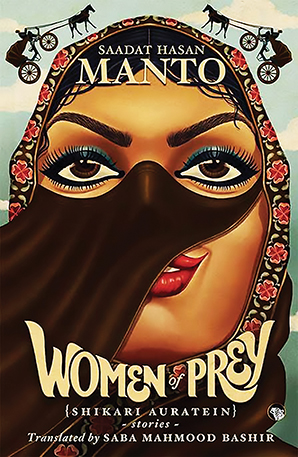

Shikari Auratein (Women of Prey) — a collection of some of Manto’s stories and sketches published in 1955, has been recently translated in English by Saba Mahmood Bashir. It shows a different side of the iconic author

IN RECENT times, Manto has been read widely. The reason could be the movies and plays that have come up in the last few years – giving a glimpse of his life and struggles. These stories also created a mystique around his personality, and made him a writer who was loved by all, across borders.

Manto was born in Ludhiana, Punjab in 1912. He failed twice in Urdu during high school and again in college during the year-end exam, which led him to drop out of college. Amritsar and Delhi both played a crucial role in the way his craft evolved, but it was only in Mumbai where his sensibilities and worldview evolved.

A biopic on Manto was made by Sarmad Khoosat in Pakistan (2015), followed by Nandita Das’s ‘Manto’(2018)in India — featuring Nawazuddin Siddiqui. Many progressive thinkers, intellectuals and youth have been influenced by his writings around Partition – as a luminary of Urdu literature who challenged middle-class morality and captured in his stories the remnants of a secular and syncretic cultural tradition overpowered by rogue communal mentality during Partition.

However, he ended up being stereotyped as a Partition writer – in fact, he is much more than that. Manto was a humorous, empathetic, complex and versatile personality.

A collection of some of his stories and sketches published in 1955 with a title Shikari Auratein (Women of Prey), marked a different side of Manto – funny, raunchy, genuinely pulpy with a subliminal Manto flavour. The book has been recently translated in English by Saba Mahmood Bashir and published by Speaking Tiger in November 2019.

As this collection shows, he was a timeless writer capturing his time in fiction. His ruthlessness while narrating stories of his time is palpable, and he never created a bar around himself based on language, more so as to not fit himself into any conventional narrative of being a writer.

“Manto went to write powerfully and with great insight and honesty about those sections of society which people are unwilling to see or discuss. In etching out his memorable characters and stories, Manto went beyond the glitter and glamour of Bombay, to illuminate the unseen corners, the invisible people of the city,” says Bashir in the introduction to the book.

Bashir is the author of Memories of Past (2016), I Swallowed the Moon: The Poetry of Gulzar (2013), and Gulzar’s Andhi: Insight into the Film (2019). The author writes in the intro of this book, “Manto’s name has come to be synonymous with his short stories set around the Partition, like Toba Tek Singh, Kali Shalwar, Boo, and Khol Do. Unfortunately, these few stories have eclipsed the complexity, range, and versatility of his work. Manto’s case is similar, to an extent, to that of his contemporary Ismat Chughtai, who is identified more with her controversial story Lihaf, than any of her other masterpieces.”

She too was not aware of the versatility of Manto until a decade back, when she read his sketches and writing in various other genres. “Manto was characteristically blunt, even brutal. He wrote what he saw, without mincing words.”

How Manto saw women is often debated, but his stories are full of female characters who were not just victims but also vindictive, clever, vile and conniving. The book also has a sketch on Sitara Devi, a legendary Kathak dancer and a very fascinating figure. Here, Manto’s writings seem like pulp fiction but respectful, non-judgemental. She was a kind of woman who can never get satisfied by one man, a free-spirited soul who never shied away from asserting her desires. Manto wrote, “In my book, she walks tall. I do not know what she thinks of me but I have always thought of her as a woman who is born once in a hundred years.”

The main story in Women of Prey is a series of anecdotes of the protagonist’s encounters with street-walkers of Lahore and Bombay. He nowhere used the word ‘prostitute’ for them, instead he just launched into a simple narration. Manto did not care about any morality and political correctness while writing about such characters. Bashir says, “For Manto, the argument was that sex, including transactional sex, is an integral part of society and there is no reason why it should be banished from literature.”

The collection is full of compelling and beautiful stories. It shows Manto beyond the profile of him in the popular imagination. Each story shows a different attribute of Manto’s personality — empathetic, cynical, funny and ironic. “If the stories and sketches in this collection are witty and gloriously outrageous, they are acidic and immensely sad too. There are many Mantos,” the translator writes.

One story in the book titled, ‘Three and a Half Annas’ is about the immorality of law and how a hungry and poor man was imprisoned for petty theft. Another story ‘Flower of Divine Mercy’ is about a man who wants to drink in peace. In order to do so, he comes up with an ingenious plan to fool his wife without getting caught.

These stories depict how simply Manto was able to write about the life of people around him —which, at hindsight looks trivial, but the rawness of Manto’s pen makes the readers uncomfortable, yet intrigues them. This rare side of his work proves a touted phrase used for him — “troubled genius”. Thus, one can say this book attempts to break Manto’s stereotypical image as a writer of partition.