When Chander Bhan Bhagoria developed an interest in Urdu through Hindi film songs and works of poets in Devanagri script in a library across his home in a tiny town of Babai in Madhya Pradesh, he began scribbling couplets and songs.

He once took them to his guru (teacher), Thakur Brij Mohan Singh, a Hindi poet of repute living in the town.

Brij Mohan looked at his writing, “lifted his face” and said, “You should write Hindi geet (songs) as you know the language. You can make a name for yourself. You don’t know the Urdu script. You won’t go far as a shaayar (Urdu poet) unless you learn.”

Also read: Raghu Rai, a new lens and beyond

Those words affected the 15-year-old deeply.

This was 1961, with India’s then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, a connoisseur of Urdu.

But in Babai in Hoshangabad district (now Narmadapuram), although a milieu of cultures and religions — there were temples, including a couple of Jain ones and a mosque, it was a challenge for the young Chander Bhan to find someone who could teach him Urdu. Besides the old fort of Gond kings, there was not much there.

He went to the Imam (leader of prayer) of the mosque who “looked at him with affection as everyone knew everyone since it was a small town and he knew my farmer dad”. But his response left him disheartened.

The Imam himself didn’t know how to write and read Urdu beyond basic.

“It broke my heart,” recalls Chander Bhan, who used to support his family working on the family’s eight acres of land as he was eldest of the nine siblings.

“I couldn’t study beyond bachelors. We were poor. But I wanted to become a poet. The Imam’s response was like the proverbial last straw breaking.”

But luck smiled and one day he travelled to nearby Bhopal, a city known for Urdu poets and a refined taste for the language. The occasion was a wedding among relatives and even though there was no chance for a 15-16-year-old to leave the wedding and barge into the house of a poet, least of all, ask him to take him as his understudy, it did give him a chance to pick a book called, ‘Hindi-Urdu Teacher’ from the platform at Bhopal railway station.

“I paid 50 paise for it. It was like manna.”

He picked the language – reading and writing probably at rudimentary level – in two months.

“I learnt without any ustaad (master) in two months. I went to Itarsi, bought Shama magazine (published from Delhi). I read it, not quickly but decently.”

He then went to Brij Mohan and read to him a Firaq Gorakhpuri poem published in Shama.

Just six months ago, the Hindi poet had advised Chander Bhan to take up Hindi poetry.

A surprised Brij Mohan said, “You can make a name for yourself. You learnt Urdu in such trying conditions.”

But that was only a little part of the battle won.

After graduation from NMV College in Hoshangabad, it was time to support the family and give up on his dream of becoming a lawyer.

“I was set for a job there only. Around that time, a mill for security paper (paper for currency notes) was starting in Hoshangabad and people there were getting jobs. Besides, I had also cleared Railways guard exam,” he recalls.

But that was only a port of call and the final destination was Delhi, “since it was a big centre for Urdu culture”.

So, in 1966, he landed at the New Delhi Railway Station on the Paharganj side and a 50-paisa tonga ride took him to Shakti Nagar where a Babai native, Babu Ram, his only acquaintance in Delhi, lived and worked as salesman at a petrol pump.

Babu Ram was 20 years older to him.

“I stayed at his home for a week and then asked him to find me work,” recalls Chander Bhan.

“He said, ‘I know only 3-4 people and that too in nearby petrol stations but will you be able to work at a petrol pump?’ I said, ‘Why not? For someone who has no jugaad (connection), even a straw is a support’.”

The 21-year-old joined as a petrol filler in a petrol pump in Model Town at a salary of Rs 60 per month.

But he kept clawing at the Urdu poetry circuit, becoming an understudy of Pandit Ram Kishan Mustar, a poet and editor of Milaap, a popular Urdu newspaper.

“I became his shaagird (understudy). He had memorised thousands of couplets of English, Persian and Urdu. My language improved gradually under his guidance. He used to say some couplet and translate and I would learn it. You can’t learn Urdu, especially poetry, just like that. It takes time. Every Saturday, I’d go to him, recite a poem and take suggestions.”

One day Mustar told Chander Bhan that he is going to meet his ustaad (teacher). He didn’t know who. They both went to Jorbagh and ended up sitting before Raghupati Sahay, an English lecturer by profession but an Urdu poet of phenomenal stature, known popularly as Firaq Gorakhpuri.

“I was pleasantly surprised — Firaq was his ustaad,” recalls Chander Bhan, who was by now writing poems as Chander Bhan ‘Chander’.

“He had his own way, wouldn’t consider anyone else even half decent. So, when Mustar Sahab told him that I say good poetry, he said, ‘Oh I see! Hmmm! Ok, recite.”

“I was sweating in anxiety. He is such a great poet, I thought. I forgot whatever I’d prepared. Then I took out the piece of paper that I had brought to show Mustar. I read it. It was a decent nazm called, ‘Samundar ka Sukoon (Calmness of the Sea)’. If you read it like poets should, it is six-minute long. But I read it so quickly that I was done in 2.5 minutes.

“After listening, Firaq sat up and said, ‘Mustar, what name did you say of this boy?’

Mustar: ‘Chander Bhan.’

Firaq: ‘What is his takhallus (a pen name added to the original name normally for Urdu poets)?’

Mustar: ‘I am thinking one for him. I don’t like the current one– Chander.’

Firaq: ‘Why do you have to think about it. He is a thoughtful poet. His name should be Khayal.’

From that day, I am known as Chander Bhan Khayal.”

This was 1970 and by that time Chander Bhan Khayal had done well as a petrol filler and been promoted as a salesman with a salary of Rs 600 besides tips and subsequently as an in-charge after “the petrol pump owner realised I am educated”.

It was around that time, Fikr Taunsvi (pen name of Ram Lal Bhatia, a post-partition refugee from Pakistan), dragged him out of life in petrol pump. Taunsvi used to write a daily column Pyaaz ke Chhilke which was widely read as the circulation of Milaap newspaper ran into lakhs across Delhi, Jalandhar and Hyderabad.

“He liked me a lot. Once he told me to give up working at petrol pump and work as journalist in an Urdu paper to stay connected with language,” recalls Khayal.

Taunsvi got him a job at Savera, an Urdu paper run by friend Jamnadas Akhtar.

“I took a massive pay-cut, from Rs 700 plus tips per month at petrol pump, I came down to Rs 150. I worked for Tej and Savera and wrote occasionally for Milaap from 1970. In 1980, I got an offer from Qaumi Awaaz (Urdu newspaper of National Herald group) which had started its edition in Delhi. I joined as sub-editor. My pay increased to Rs 600.

“I’d translate English news to Urdu. Besides translating, I’d proofread, make page and paste news on it. Newspaper work was cumbersome back then.”

However, it gave him opportunity to stay in touch with men of letters and pursue poetry.

“I used to do poetry too, visit events. The times were inexpensive and needs were few. DTC bus tickets would cost 5, 10 and 15 paise. Dhabas (roadside eateries) were cheap – you paid 10 paise for roti. Daal (pulse curry) would be free. Bade papad belne pade (I had to grind a lot).”

The fruits began to sprout. In 1979, he came up with Sholon ka Shajar (Tree of Flames), a 45-poem and 112-page collection.

“Since I had come from an area that had no background of Urdu poetry, my work included the Satpura, the Vindhyachal and Narmada jungle. It was new diction and atmosphere for Urdu poetry. People realised I was saying something new. It gave me overnight recognition in India and Pakistan.”

It was published by Satoor Prakashan, run by friend and Urdu poet Kumar Pashi, but Khayal had to pay the publishing cost.

The second book, Gumshuda Aadmi ka Intezaar (The wait for the lost man) in 1996, took time because of his job.

He had switched to reporting and began covering Delhi government since the assembly was re-established in 1993 after four decades. But he kept attending poetry gatherings and seminars.

“It was tough to balance both as I wouldn’t get leave since I was reporting a lot. But I managed.”

His work, Laulak (If not for you), a work in praise of Muhammad, the Islamic prophet, came out in “2002 after 10-11 years of work and is unique as a poem in a book form, catapulting me to international fame”.

Subah Mashriq ki Azaan (Morning call of the East), a collection of poems on various subjects, came out in 2008.

Then there was another, Ehsaas ki Aanch (Heat of the feelings), in 2015.

The latest work, Taaza Hawa ki Taabishein (The brilliance of fresh breeze), which is a collection of poems, discusses pain and agony of someone like himself brought up in multi-cultural and multi-religious atmosphere, having to live in a deeply polarising world.

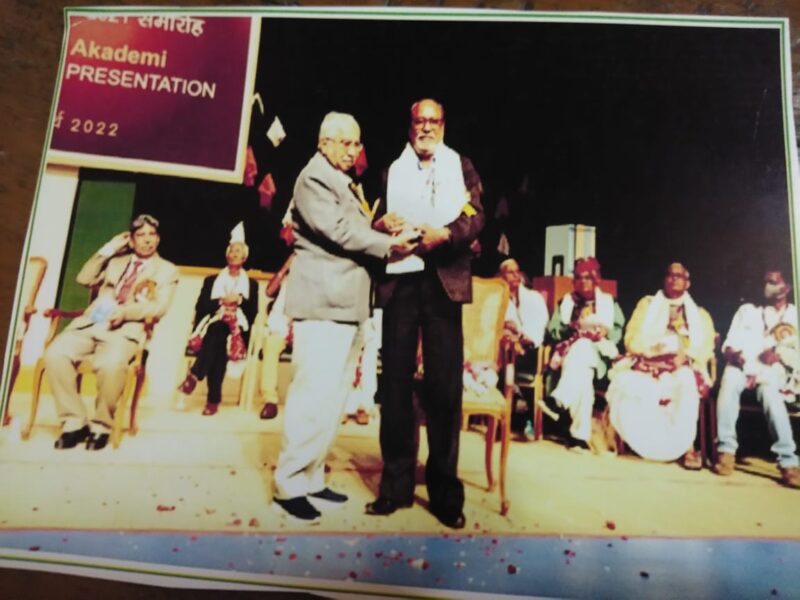

That work got him the 2021 Sahitya Akademi Award, the pinnacle of literary recognition, “a sweet reward for a bitter-sweet journey”.