Tej Singh Jaglan, a businessman from the Jat-dominated village of Deoli in South Delhi, isn’t particularly interested in the new Sunny Deol-starrer Jaat. He doesn’t plan to watch it either. “The children in the family want to see it,” he says with a shrug. Whether the film will resonate with Delhi’s Jat audiences remains to be seen.

Yet, for many Jats in the capital, identity doesn’t hinge on cinema. It’s embedded in the very land they inhabit—and in the quiet traditions that persist even as Delhi transforms rapidly around them.

A Capital woven with villages

It’s easy to forget that Delhi, with its sprawling colonies and urban bustle, is also a city of villages. Stretching from Narela in the north to Mehrauli in the south, Jat-dominated villages are deeply rooted in the city’s landscape. It is believed that nearly 80% of Delhi’s villages have a Jat majority.

Most of today’s posh colonies were once agricultural land owned by Jats. Munirka gave way to RK Puram. Vasant Vihar rose next to Vasant Village. Kishangarh lies beside Vasant Kunj. Shahpur Jat now borders the Asian Games Village.

Safdarjung Enclave adjoins

Mohammadpur. Farming once flourished here, and while it has declined in many places, it hasn’t disappeared entirely.

The village spirit survives—in hookahs, chaupals, community panchayats, and women who still cover their heads with dupattas. Even amid rising apartment blocks, the old ways echo softly.

A legacy of land—and loss

The transformation from farmland to cityscape began in earnest in the 1980s, as unauthorised colonies sprang up in Jat-dominated areas like Palam, Uttam Nagar, Nasirpur, Nangloi, Mundka, Nawada, and others. As parcels of land were sold, Jats earned substantial sums—but the consequences were complex.

The first waves of government land acquisition took place in areas like Munirka and Vasant Vihar for Jawaharlal Nehru University, and Jia Sarai, Ber Sarai, and Katwaria Sarai for IIT Delhi. The gains were real, but so were the disruptions.

Many Jat families, once firmly agricultural, struggled to adapt to urban ways. Like their counterparts in neighbouring Haryana, Jats in Delhi traditionally joined the army in large numbers. But that trend has waned.

Today, some still live in their ancestral villages. Others have shifted to flats or other cities, leaving behind caretakers to collect rent and manage properties. A few wisely reinvested in farmland elsewhere—in Gurugram and beyond—resuming farming on new soil.

Gotras, Gaushalas and village pride

Despite these changes, some things haven’t shifted. Gotra identity remains central. In most Jat-dominated villages, a single gotra dominates. The Tokas dominate in Munirka, Mohammadpur, Hauz Khas, and Humayunpur. The Maan gotra is found in Khera Khurd, Holambi, Naya Bans, and Alipur.

Dabas families are concentrated in Madanpur and Kanjhawala. Sehrawats dominate Bawana and Mahipalpur. Solankis are prominent in Palam, Surakhpur, Shahbad Mohammadpur, Dabri, Pooth Kalan, Asalatpur, Matiala, and Baprola. The Rana gotra is common in Qutubgarh and Mungeshpur, while Maliks dominate Masoodpur.

Also Read: The Hakim behind summer favourite: Rooh Afza

“Delhi’s Jats take their gotras very seriously,” says Jaglan. “They’re not ready to move away from it.” Marriages within the same gotra are strictly prohibited. Most weddings take place within Delhi or in nearby villages of Haryana.

Gaushalas, or cow shelters, also hold a special place in Jat life. Families contribute fodder and money according to their capacity, and religious customs remain strong.

Three temples are central to their spiritual life. The Baba Gangnath Mandir in Munirka, the Haridas Mandir in Jharoda Kalan, and the Sheetla Mata Mandir in Gurugram are all considered sacred spaces. Jats visit these temples on auspicious occasions, from mundan ceremonies to marriages.

Who represents the Jat spirit?

The Jats of Delhi have produced many notable figures across fields—from sport to academia, business to government service.

Virender Sehwag, the former Indian cricketer, is a widely admired role model. “Despite hardships, he made his mark in international cricket,” says a resident.

Ram Singh, Director of the Delhi School of Economics, is another source of pride.

“Dr Ram Singh is a very respected teacher and economist. He is adored by one and all. Our Jat community is also proud of his achievements,” says Pankaj S Lather, Joint Director, Delhi Skill and Entrepreneurship University.

Manushi Chhillar, a former Miss World, doctor, and actor, is admired by many young people. “Manushi is also an actor and a qualified doctor. She is an alumnus of St Thomas School, Mandir Marg,” adds Lather.

Other prominent Jats include KP Singh, Chairman of DLF; Karnail Singh, former Director of the Enforcement Directorate; and Khajan Singh, an Asian Games bronze medallist.

Education: An uphill road

Despite these success stories, many in the community face systemic challenges—especially in education.

“The government’s attitude towards education in villages has been lukewarm,” says Choudhary Surinder Solanki, head of the Palam Khap Panchayat.

In most government schools in Jat villages, Science and Commerce streams are missing, severely limiting the options available to rural youth.

There are only three colleges specifically catering to Delhi’s rural students. These are Aditi Mahavidyalaya in Bawana, Swami Shraddhanand College in Alipur, and Bhagini Nivedita College in Najafgarh.

The gap between aspiration and opportunity remains wide.

A shrinking presence

Ask a Jat how long their family has lived in a village, and you may hear: “400 years… 600… even 700 years.”

“My forefathers came to Palam more than 700 years ago,” says Solanki. And yet, the sons of the soil are now becoming minorities in their own villages.

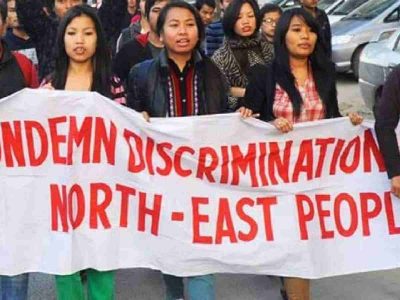

Migrants from Bihar, Odisha, the Northeast and beyond now rent homes in these villages. Some Jat families have moved out, while others send representatives to manage affairs—from rent collection to local issues.

Meanwhile, villages with significant Tyagi, Gujjar, Ahir, Yadav and even Brahmin populations also exist across the capital, creating a complex rural social fabric.

Between past and present

Delhi’s Jats occupy a peculiar space—firmly rooted, yet constantly adapting. Their villages form the underlayer of the capital’s modern cityscape. Their culture lives on in temples, Gaushalas, and gotras. Their heroes span cricket fields and classrooms. But their challenges—land displacement, educational gaps, and demographic change—reflect deeper tensions.

In this half-village, half-metropolis world, the story of Delhi’s Jats continues—complex, proud, and evolving.