Love, marriage, intimacy, rape and harassment – there is a law to deal with all these personal matters. This book attempts to put it all the Supreme Court rulings in easily understandable language

This anthology edited by Saurabh Kirpal has 10 essays by lawyers, activists and judges, besides two by the editor. The blurb tells us it is “an invaluable record for posterity – for it reveals the power of the country’s courts to uphold the privacy, dignity and safety of its citizens.” This claim, of course, should be taken with a pinch of salt as the dignity of citizens is often hammered by the tension and headaches of prolonged litigation. An irreverent person might well look at the dates when enlightened rulings came from the court, and ask, ‘What took you so long?’

Having studied law at Oxford and Cambridge, Kirpal returned to Delhi and has been practising at the Supreme Court for over two decades. His major claim to fame came when Section 377 was removed from the Indian Penal Code in 2018. So much is already known about this legal battle that this review would rather focus on matters about which the general public has very little knowledge.

In the chapter ‘From Adultery to Sexual Automoy’, Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Kathju tell us, “Section 497 IPC did not criminalise adultery because it damaged the marriage of two persons, for if this were the law’s intention, then extramarital sexual relations by either spouse should have been penalised.” Since it was based on Victorian values, it regarded a husband whose wife cheated as an aggrieved party but not a wife whose husband cheated on her, as she was regarded as mere property. ‘Enticement’ and abetment of the affair could also be penalised.

In this context, it is also interesting to note that before the enactment of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, the law permitted Hindu men to marry multiple women, that is, to be polygamous. This law was a result of an understanding that Hindu customs needed to be codified, as were the Hindu Succession Act, the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act and the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, all three passed in 1956. Orthodox people opposed the laws, including then President Rajendra Prasad, but they got through. It was only 50 years later that the Triple Talaq Bill was passed amid raging controversy, that too after a 2018 ruling by the Supreme Court striking down this practice as null and void.

Despite a number of cases being filed in various courts challenging these provisions, it was decades after Independence, in 2018, that Supreme Court Justice Chandrachud finally said, “Marriage is a constitutional regime founded the equality of and between spouses. Each of them is entitled to the same liberty which Part III guaranteed.”

In the Manusmriti, it is apparently laid down that “those men who are addicted to intercourse with the wives of other men, the king shall banish after having branded them with terror-inspiring punishments. For out of that arises the admixture of castes among people, when follows root-rending unrighteousness, tending to total destruction.” So it was really a way of preserving purity of caste. Also Brahmins were expected to marry women with auspicious bodily marks. Our ancestors lived in interesting times.

One of His Lordships wrote rather evocatively of what an ideal relationship is like:

‘Sexual intimacy brings spouses wholeness and oneness. It is a gift and a participation in the mystery of creation. It is a deep sense of spiritual communion…”

But then comes the catch. The honourable judge says if the wife displays indifference to the man’s overtures and refuses to get intimate with him, he may “legally seek the court’s intervention to declare her psychologically incapacitated to fulfil an essential marital obligation.” The judge is kind enough to add that he should not be coercive and violent. This whole scenario is misleading and disingenuous. What if the husband is not able to arouse her because of his ineptness or general lack of hygiene. What if she is too tired to respond? What if he cannot get it up because he finds her too intimidating?

And the reverse can also be true. A wife can be aggrieved because of her husband’s lack of sex drive due to alcoholism or mid-life crisis, or because relations between them are fraught due to domestic discord. Would this be enough reason for her to sue him for divorce?

The twists and turns of the legal cases enumerated in this book, as they wound their way through our torturous judicial system, may not interest the lay reader but are undoubtedly of interest to lawyers, who make so much money out of prolonged legislation. Older people feel ashamed when they tell the younger generation that British colonial laws are still in force. There was a time when the UPA government said it would reform 100 antiquated laws but it fell out of power and the momentum was lost. For them, the title of this book may make the judicial system seem sexy, but that is far from the case. Probably, they only want to know when same-sex marriage is allowed. No doubt, gay rights activists are working on the issue but the Establishment moves like an elephant, not a nimble-footed horse.

Still, for those interested in braving the task of approaching the Supreme Court in all its majesty, it is heartening to learn that the court can be approached by any random person to get justice. A contributor to this volume, Mukul Rohatgi, explains in the essay ‘An Axis Shift’, “The rule of locus standi requires any person who approaches the Court to have some personal interest in the litigation. The courts do not encourage busybodies. In the case of Public Interest Litigation (PIL), the strictness of the rule has been reduced. The Court has acknowledged that in the case of PILs, there may be disadvantaged groups who cannot fight their own battles. Hence, even strangers may file cases on their behalf.”

In his essay ‘Love and Marriage’, editor of the anthology Saurabh Kirpal says bluntly, “Historically, marriage has been more about property rights and getting the right in-laws. Love was neither a necessary nor a sufficient reason to get married.” This dispassionate arrangement changed, he says, when women started working and seeking their own partners. In his view, the laws must change when society changes.

The reverse seems to have happened when the Supreme Court recognised the rights of partners in a live-in relationship. This was done in 2005 under the provisions of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. Society was clearly not ready for this, as seen in the attitudes of landlords when renting out their apartments, or the secrecy they themselves find necessary in order to be able to walk in and out of their homes with dignity. However, as couple defy their parents to co-habit, the older generation ends up accepting and forgiving – also because they don’t have any right to dictate the living arrangements of their adult children.

The book also has chapter on Sex and Religion, Sexual Harassment at the Workplace, and other topics which have already got a lot of media attention. No doubt, after the wide exposure given to Sushant Singh Rajput’s relationship with Rhea Chakraborty, the highest court in the land might one day have to decide whether a grown man of 34 years can be induced by his girlfriend to take drugs. And when a man should be abandoned when he is depressed, or whether his family is liable for neglect. The devil, clearly, lies in the details.

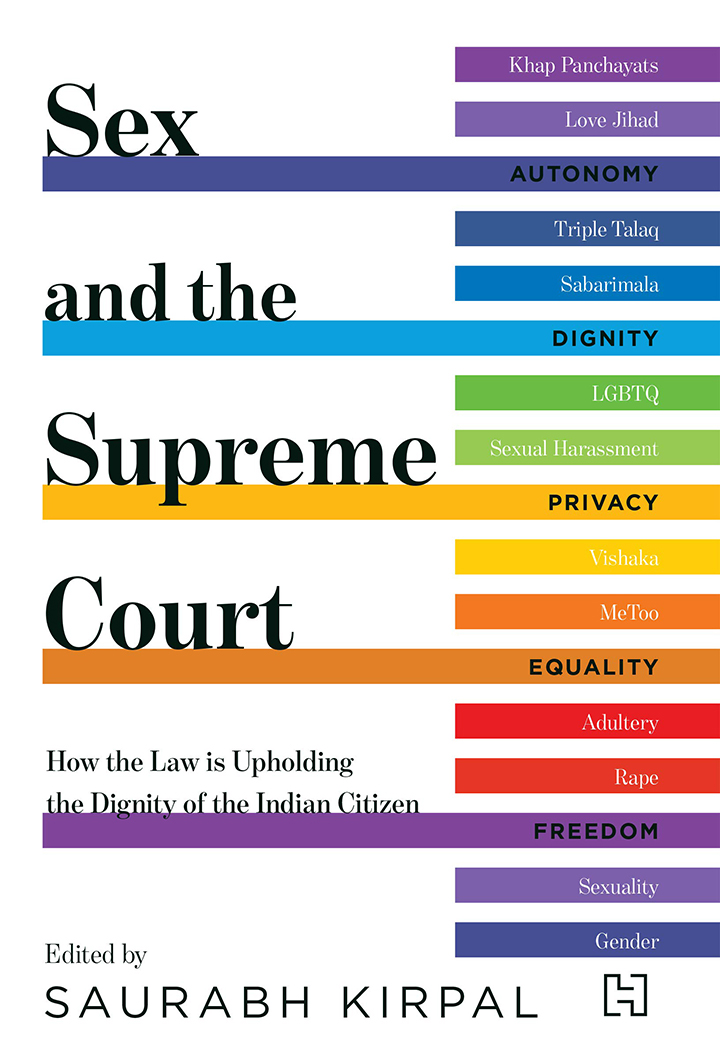

Sex and the Supreme Court

Edited by Saurabh Kirpal

HarperCollins, pp 345, Price Rs 699/-