When the Delhi Assembly passed the Delhi School Education (Transparency in Fixation and Regulation of Fees) Bill, 2025, it was hailed as a landmark reform — a supposed victory for parents long weary of arbitrary private school fee hikes. But beneath the rhetoric of transparency and parental empowerment lies a troubling reality: the legislation contains gaps that may give private schools greater legal cover to escalate charges.

After examining the bill closely, experts told Patriot several flaws in the bill leave parents vulnerable to unjustified demands. For thousands of families across the Capital who had pinned their hopes on this law, the fine print tells a different story — one in which “reform” could simply replace one set of vulnerabilities with another.

The sales pitch and the reality

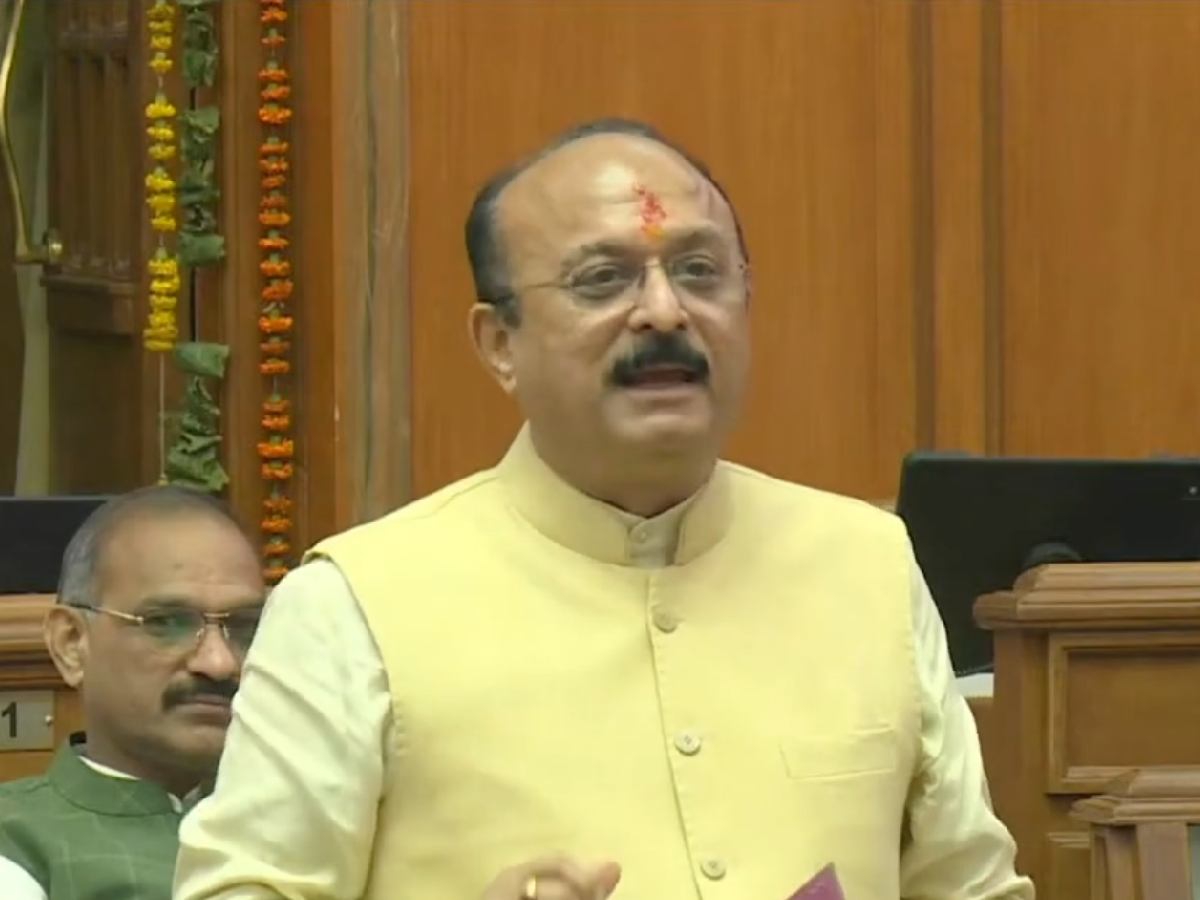

Speaking in the Assembly, Delhi Education Minister Ashish Sood described the bill as “the most democratic bill ever introduced” on school fee regulation. He claimed it “empowers parents to actively participate in the decision-making process” and “ensures transparency while safeguarding families from unjustified fee hikes.”

It was a powerful pitch — the kind that draws applause and headlines. But parents’ associations and education policy experts argue that this is where the trap begins: well-crafted promises masking structural weaknesses.

They contend that the bill is less a protective shield for parents and more a blueprint that private schools can exploit. In its review, Patriot found multiple provisions that either skirt core accountability issues or create new avenues for fee hikes.

Also Read: Delhi’s Yamuna choked by sewage treatment failures

The PTA problem: transparency in name only

Chapter 2, Section 1(a) mandates that “Every school shall constitute a Parents Teachers Association (PTA) following such guidelines as may be prescribed.”

On the surface, this appears progressive — institutionalising parental input through PTAs. But the bill fails to specify which guidelines will govern their formation and elections. Without uniform rules, schools can dictate their own processes, leaving parents without meaningful representation.

More strikingly, the bill provides no standard mechanism for PTA elections. Many schools currently use Google Forms for voting — a method inaccessible to less tech-savvy parents and vulnerable to manipulation. Parents allege that in some cases, these forms are even filled out by students on their behalf.

While the bill cross-references the Delhi School Education Act, 1973, for PTA constitution, but that Act also lacks a concrete structure for elections. Questions remain unanswered: Who will serve as the returning officer? How will votes be verified? Who will audit the process?

Aparajita Gautam, President of the Delhi Parents Association, notes that PTA election guidelines were last clearly outlined in 2010 and have been inconsistently applied ever since. “Every school is doing it their own way,” she says. “Some use Google Forms, some vote by show of hands, others use completely opaque methods. The new bill should have ended this confusion. Instead, it’s silent on the most crucial details.”

A legalised menu for profiteering

Chapter 1, Section 2(6) lists 10 permissible fee heads — tuition fees, term fees, library fees, laboratory fees, caution money, examination fees, hostel fees, physical education fees, development fees, and deposit as security.

This broad list undermines the bill’s stated purpose of preventing arbitrary charges. The legislation does not define “tuition fee”, leaving room for inflated charges. It also introduces a new “term fee” category, allowing schools to levy up to one month’s tuition fee per term. With two terms a year, this effectively adds the equivalent of two extra months’ tuition.

Library and laboratory fees, often covered under tuition, are now separate charges. Physical education fees monetise activities and staff salaries that are standard components of schooling. The development fee clause allows schools offering education up to Class 12 to collect this fee annually, guaranteeing a steady revenue stream.

These provisions run counter to the recommendations of the Justice Santosh Duggal Committee, which sought to limit fee heads to a few essential categories and prevent duplication. Endorsed by the Directorate of Education, the Duggal framework was designed to protect parents from being nickel-and-dimed. Instead, the new bill dismantles these safeguards.

Also read: Balding Before 20? Early hair loss is bigger menace than you thought

Vague criteria for fee determination

Chapter 2, Section 8 outlines the factors to be considered by the school-level fee regulation committee, including the school’s location, infrastructure, facilities listed in the prospectus or on its website, and overall academic standards.

It also mentions administrative and maintenance expenses, surplus funds from individuals (including NRIs) or government grants, staff qualifications and salaries, and a “reasonable” provision for salary increments. Schools must assess how much of their income is spent directly on students and ensure any revenue surplus remains within limits, along with “any other relevant factor” specified by authorities.

Critics say these criteria are vague and open to abuse. Allowing schools to base fees on claims in their own prospectus or website creates a convenient loophole for inflated charges. Schools could justify hikes by making unverifiable assertions such as being among the “top 10” in an area or offering “the best education”.

Another listed factor — “the education standard of the school” — raises questions about measurement. What parameters will determine such a standard, and who will assess them? The bill offers no answers.

Parents call it a bill for the ‘school mafia’

For Gautam, the message is clear: “This bill has been drafted to benefit school mafias, making profiteering legal through legislative cover.” She argues that by multiplying fee heads, failing to define key terms, and allowing self-certified facilities to justify hikes, the bill creates “a clear path for private schools to openly loot parents in Delhi.”

She is equally critical of the political handling. “It is very disheartening that even the opposition did not raise these concerns during the Assembly debate. It shows that political leaders — including AAP MLAs — are complicit, or at least unwilling to challenge the private school lobby,” she says.

Her appeal is blunt: scrap the bill and rebuild it from scratch with input from education policy experts who have a proven track record.

Manoj Kumar, Advocate and Vice President of DPA, said that instead of bringing this ‘vague’ bill to benefit private schools in the national capital, the Delhi government should have given the democratic rights to the 12 parents who were appointed to the School Management Committee (SMC).

“The parents representing each standard from Class 1 to 12 can clearly make decisions which are in the best interest of the students,” Kumar said.

“This bill has only left the parents more vulnerable and helped the schools in doing the profiteering through a legal way now,” Kumar added.

Pankaj Gupta, General Secretary of North-West Parents Association (NWPA), said, “This bill has broken the backbone of the parents and by passing it in the assembly is empowering the private schools to collect the unjustified fee by adding the new sub-heads. This is clearly undermining the recommendations of the Duggal Committee, which has given the sub-heads under which the schools can charge fees from parents to protect them from arbitrary fees.”

“The bill has not taken even a single measure to protect the parents in the, instead the authorities have stripped parents of their rights to raise complaints by announcing that the 15% majority should be mandatory even for raising concerns,” Gupta concluded.