DURING AN ECONOMIC slowdown, a recession, or a depression for that matter, economists become one trick ponies. Most of them go back to John Maynard Keynes, an economist who lived during the first half of the 20th century.

Keynes’s major contribution to economics was explaining the Great Depression of 1929. He explained the situation prevailing at that time, in large parts of the Western world, somewhat like this: when stock prices and commodity prices fell in 1929, across large parts of the Western world, a certain section of the population started to cut back on its expenditure. If a single person cuts back on his expenditure, it makes tremendous sense. But if a significant section of the population cuts back, there is a problem — the logic being that one person’s spending is another person’s income.

If a substantial section of the population cuts its spending, the income of another section of the population is impacted. This section could include big businessmen or even the corner store down the road. This is because the expenditure of one person was the income for another. When expenditure is reduced, incomes fall, leading to a further reduction in expenditure. This slows down economic growth, or leads to the “contraction” (recession) or “huge contraction” (depression) of the economy.

So, what was the way out of this situation?

Keynes suggested that during times such as the Great Depression, cutting interest rates to low levels would not tempt either people or businesses to borrow because of the tight economic situation. One way out was cutting taxes so that people would have more to spend. But the best way was for the government to spend more money, and become the spender of the last resort. Also, it did not matter if the government ended up running a fiscal deficit in doing so. Fiscal deficit is the difference between what a government earns and what it spends.

Keynes came up with this prescription sometime in the mid-1930s. While he was expounding on his theory, it was already put into practice by Adolf Hitler, who had deployed 1,00,000 workers for the construction of the Autobahn, a nationally coordinated motorway system in Germany that was supposed to have no speed limits. By 1936, the German economy was chugging along nicely, having recovered from a devastating slump and unemployment in the aftermath of the First World War. Italy and Japan had also followed a similar strategy. These countries had not bothered about their fiscal deficits, because they had hoped to pay them off by waging war.

Very soon, Great Britain would end up doing what Keynes had been recommending. Great Britain had more or less done away with both its army and air force after the First World War. But the rise of Hitler led to a situation where massive defence capabilities had to be built within a very short period of time. The prime minister at the time, Neville Chamberlain, was in no position to raise taxes to finance defence expenditure. Instead, he borrowed money from the public.

By the time the Second World War started in 1939, the British fiscal deficit was already projected to be around £1 billion, or around 25 percent of the national income. The deficit spending, which started to happen even before the Second World War, led to a boom in the British economy — especially in the south of England, where ports and bases were being expanded and ammunition factories were being built.

This left very little doubt in the minds of politicians, economists and people around the world that the economy worked the way Keynes said it did. Lest we come to the conclusion that Keynes was an advocate of a government running high fiscal deficits all the time, it needs to be clarified that his stated position was far from this.

Keynes essentially believed that during recessions or depression, trying to balance the budget, or ensuring that income matches expenditure, was not the best thing for a government to do. In a recessionary environment, chances were that the government’s income would fall because of lower tax collection. The only way to balance a budget would be to raise existing taxes, introduce new ones, or cut expenditure. Any of these measures would squeeze the economy further.

Keynes believed that on average, the government budget should be balanced. This meant that during years of prosperity, governments should run fiscal surpluses; that is, its income should be more than its expenditure. But when the environment is recessionary, governments should spend more than what they earn, even running fiscal deficits.

But over the decades, politicians and economists, took one part of Keynes’ argument and ran with it. The idea of running deficits during bad times has become permanently etched in their minds. However, they forgot that Keynes had also wanted them to run surpluses during good times.

Dear reader, by now, you’re probably wondering why I’m talking about history in a piece on the budget of the government of India, scheduled to be presented on February 1, 2020. Sometimes, it’s important to know where a particular idea is coming from and in order to understand that it is important to know our history.

Hold this thought, because we will come back to it.

Reading India’s economic slowdown

India is currently going through an economic slowdown. The economic growth in 2019-20, as measured by the growth in the gross domestic product, is expected to be at 5 percent in real terms (adjusted for inflation) and 7.5 percent in nominal terms (not adjusted for inflation).

Note: The numbers used from here on are all in nominal terms.

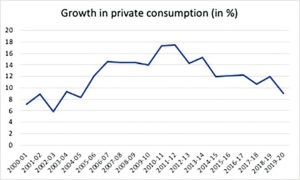

Economic growth has slowed down primarily because private consumption has slowed down. Take a look at Figure 1, which plots the growth in private consumption expenditure over the years in nominal terms. Private consumption expenditure is the money you and I spend on buying goods and services.

Private consumption in 2019-20 is expected to grow at 9 percent, the slowest in nearly a decade and a half. This is happening primarily because of a slowdown in income growth. Take a look at Figure 2, which basically plots per capita disposable income growth over the years in nominal terms.

Figure 2 makes for very interesting reading, given that this is where the heart of the Indian economic slowdown lies. Income growth in 2019-20 is expected to settle at 6.7 percent, the slowest since 2002-03. Hence, after adjusting for inflation, 2019-20 will barely see any increase in disposable income.

In this scenario, it is not surprising that consumption has taken a backseat.

In nominal terms, private consumption forms about 60 percent of the Indian economy. Hence, a slowdown in private consumption has essentially ensured that the overall Indian economy has slowed down as well.

Of course, it is important to clarify that we are not in a recession. A recession happens when economic growth contracts for two consecutive quarters, or periods of three months. While India is not in a recession, income growth and consumption have slowed down dramatically in 2019-20.

In this scenario, politicians and economists, have gone back to Keynes and have asked and/or recommended fiscal expansion, or the government spending significantly more money in 2020-21 than it has in the past.

The idea, as always, is that individuals and private corporations are not spending money. In this scenario, the government needs to become the spender of the last resort and drive the economy forward.

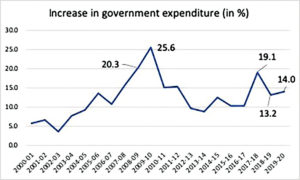

The trouble is that this has already been happening over the last two years. Let’s take a look at Figure 3, which plots the increase in government expenditure over the years, in nominal terms.

In 2019-20, the government expenditure in the economy is expected to grow at 14 percent, the fastest among all the constituents of the budget — the other constituents being private consumption expenditure, investment, and net exports (imports minus exports). Government expenditure has grown fast even in the past two financial years as well and propped up economic growth.

It needs to be mentioned here that this increase in government expenditure doesn’t fully show in the fiscal deficit of the central government and the fiscal deficits of the state governments, because a lot of government expenditure in recent years has been off-budget borrowing. If we were to add the fiscal deficit of the central government, the fiscal deficits of the state governments, the off-budget borrowings of the government, and the borrowings by the public sector (like loss-making companies getting bank loans simply because they are owned by the government), the public sector borrowing requirement — as its called — comes to close to 9 percent of the GDP. The central government’s budgeted fiscal deficit for 2019-20 is expected to be at 3.3 percent of the GDP.

This is nothing but a joke that the central government is playing on itself.

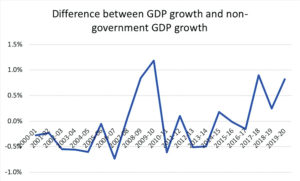

Take a look at Figure 4, which basically plots the difference between GDP growth and non-government GDP growth (or what we can call private-sector growth). If we subtract the government expenditure from the GDP, what remains is non-government GDP growth.

Figure 4 tells us that the difference between GDP growth and non-government GDP growth has been in positive territory over the last few years. What does that mean? It means that the overall GDP is growing faster than non-government GDP. So, the overall economy is growing faster than the non-government part of the economy.

In 2019-20, the overall economy is expected to grow by 7.5 percent and the non-government part by 6.7 percent, leading to a difference of 80 basis points. One basis point is one-hundredth of a percentage.

This has been the story over the last two years as well. What does this tell us? It tells us that the government expenditure has been pumping up the economy over the last few years. Also, despite the government expenditure, the private part of the economy continues to grow slower than the overall economy, which is never a good sign given that it forms around 90 percent of the economy. The government expenditure growth clearly hasn’t seeped into the private part of the economy and helped in its revival. Any genuine economic revival will not be possible unless this part of the economy revives.

So, politicians and economists who have been recommending fiscal expansion either don’t know this, or want the government to increase its spending even more. This is where things get interesting.

In 2019-20, the government expenditure is expected to grow by 14 percent. Let’s say in 2020-21, the government expenditure grows by 20 percent or more (for it to be significantly more than the growth in 2019-20). What happens then?

Look again at Figure 3. The last time government expenditure grew by more than 20 percent was in 2008-09 and 2009-10, when it grew by 20.3 percent and 25.6 percent, respectively. This clearly had a huge impact on economic growth with the economy growing, in nominal terms, by 15.5 percent and 19.9 percent in 2009-10 and 2010-11, respectively.

The easy spending policy of the government led to double-digit inflation that the country had to battle for more than a few years. The government going overboard on spending can cause higher inflation, as a greater amount of money in the hands of the people chases the same set of goods and services. This is never a good thing because it hurts the poor the most (especially food inflation). This inflation ensured that the real economic growth collapsed to 5-6 percent in the years to come, post 2010-11.

It was as if the government had brought forward economic growth by spending more in particular years, only to have to bear the cost of it in the years to come. The period also led to public sector banks accumulating a huge amount of bad loans, something for which the economy is still paying.

As is often said in economics, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

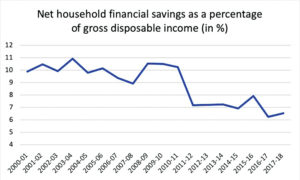

The second point here is that the net household financial savings have been falling over the years. “Net household financial savings” refers to the investments that households make in fixed deposits, insurance policies, mutual funds, etc, minus the liabilities they accumulate. Why are they important? Because it is these savings which help the government finance the fiscal deficit.

If the central government decides to increase its expenditure in the 2020-21 budget, the question is: where will that money come from? More than likely, the government will have to borrow that money. Before we get into understanding the repercussions of this, take a look at Figure 5, which basically plots the net financial savings of households over the years.

Net household financial savings have fallen over the last few years. It happened for a very simple reason: the income growth has slowed down. This has led to people having to either borrow or spend a greater proportion of their income to keep the consumption going. This has now started to break down.

The data for net household financial savings is available only until 2017-18. But given the even slower growth of income in 2019-20, the situation could only have worsened.

In this environment, if the government decides to spend more and borrow more, it will end up leaving less money for everyone else to borrow. Hence, interest rates will either go up or continue to remain high. Take a look at Figure 6, which basically plots the weighted average interest rates at which banks lend.

Figure 6 tells us that the interest rates at which banks have lent money have more or less been flat over the last two years. The reason for this, as elaborated earlier, is the fall in net household financial savings. So, increasing government expenditure by a huge amount will only add to the problem and push up interest rates. And as long as interest rates are high, the corporate sector will not be interested in borrowing and expanding. (Of course, high interest rates are not the only reason holding the corporate sector back.)

One way out of this is the government being able to raise the revenue required to finance the added expenditure. This cannot be earned through higher taxes — that would defeat the entire purpose. But if the government decides to sell assets (its shares in public sector entities, and the land and other physical assets that it owns), then the situation might be different. The problem is that the scale at which this will have to be done has never been attempted before. And the government’s past attempts at selling public sector entities have been, at best, lackadaisical.

To cut a long story short, there is very little that the government can do in the budget to revive the Indian economy. The government budget is, ultimately, a financial account. And financial accounts, ultimately, are financial accounts and nothing more. Keynes’s formula doesn’t always work, at least not in the way it should.

But that doesn’t mean all hope is lost, or that nothing can be done. There is a lot that can be done in the normal scheme of things. And that’s what we will look at in the next piece in this series.

Watch this space.

Vivek Kaul is the author of the Easy Money trilogy.

www.newslaundry.com