The lockdown resulted in loss of livelihood for migrant labour as well as self-employed artisans like potters, tailors and barbers, much more than Brahmin priests and other upper castes. On top of that, they were disadvantaged when it came to online classes, as they did not have smartphones to give their children. The social evil of untouchability reared its head again as the middle class barred domestic workers, believing them to be carriers of the disease. People from the North-east suffered on the same count

When PM Modi announced the nationwide lockdown on March 25, it resulted in a huge humanitarian crisis — the stringent lockdown caused joblessness, dislocation of migrant workers and food insecurity. Many labourers who decided to walk back home, taking a tough route, faced a lot of difficulties — police brutality, harassment for breaking lockdown rules, vulnerability to Covid infection and many more. And even those who stayed back faced problems like non-payment of wages and joblessness, among others.

The impact of the lockdown, however, was not the same across all social identities. Though job loss and possibility of infection cut across all social identities, some are more vulnerable to the risk and badly hit by the impact of the lockdown.

Caste groups who traditionally work in caste-based professions also faced difficulties during the Covid lockdown. But the challenges varied: for instance, Brahmin pujaris were invited to homes even during the lockdown but in a limited manner. Now they are slowly resuming their work.

Professions like tailors, and barbers and potters who are self-employed could not do business, a situation with which they are still coping. So-called ‘lower castes’ and Dalits were worst hit due to their representations in vulnerable, insecure work.

A recent paper by Ashoka University on the critical role of social identities on lockdown-induced job losses says, “Socially marginalised groups would be at higher risk of mortality due to Covid-19. The risks extend beyond mortality as the economic consequences of the current pandemic are likely to be most concentrated among the low wage earners and less educated workers, segments of the labour force where racial and ethnic minorities are overrepresented.”

The paper examined the impact of lockdown on various caste groups but as is the global trend, job losses were high among those communities with low levels of human capital and no security of tenure. “All caste groups lost jobs in the first month of the lockdown, the loss was the lowest for upper castes (6.8 percentage points). The stigmatised caste groups — OBC, SC and ST — all lost significantly more compared to UCs [upper castes]. The gap was the highest between SCs and UCs; the probability of job loss for SCs was 14 percentage points higher than that for UCs, in other words, the rate of job loss was three times higher for the SCs.”

This crisis has left the marginalised communities at the receiving end. The lower caste groups, SCs, STs not only faced loss of work, crisis of food security, health crisis but also identity-based discrimination. Many people we spoke to complained about the fear among upper castes that lower caste are carriers of the virus. Domestic workers, for instance, were barred by gated communities well after the lockdown.

The unorganised sector, self-employed, migrant and homeless, including also the sexual minorities and people with disability, mostly belong to stigmatised caste groups — Dalit, Adivasi, Pasmanda and Bahujan communities. Only 3% of the upper castes are daily wage earners while among SCs they are 16%.

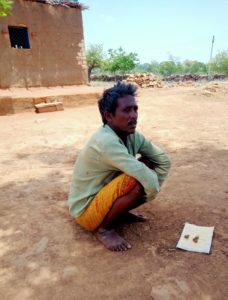

We visited a village called Kunwarpur where footloose migrant labourers from the Saharia community had returned. They told us that they are dependent on the government for rations and also for work, as they don’t have seasonal employment of plucking tendu leaves this year.

Puran Adivasi along with his family goes to Agra to work on farms, harvesting potatoes every year. But this year the sudden lockdown left his family with no work and dependent for everything on the state.

Not just Saharia tribes but the family of Chaturbhuj, a member of Gadia Lohar community, a ‘Ghumantu tribe’ is also faced with a host of the problems caused by lockdown. They do not work as labourers but their traditional work has been impacted. They could not sell the items they make, first due to Covid lockdown and second because residents are not allowing them to enter their localities.

Both of these ST communities had insecurity of work but since Gadia Lohar has their own traditional work — they were relatively better off than Saharias.

Some Jatav (a Dalit caste) youths, who were working as labourers in Rajasthan’s Pali district decided to go back home as the factory has been shut since 22 March. Vinod Jatav, 22 told us, “I was there till 29 March but since everyone was going home I too decided to return. Therefore, I started walking with my friends. It took us two days to complete the journey and we arrived here on 30 March.”

He, along with two of his friends are still in his village without work. Vinod told us over the phone that he is planning to go back as his owner is asking them to return, “Our savings have dried up and we want to go back there, there is nothing for us here.”

We spoke with members of the Pal community, which is a branch of the Kumbhakar (potter) caste in West Bengal.

Artists from the idol-making Pal community in West Bengal are facing trouble due to Covid. The labour force working for them have either had to be fired, left their jobs or are working on lower wages.

Ananda Pal is a resident of Abdalpur, North 24-Parganas. He has a family of four members: two children, one in college, one in school and a wife. His family also helps him in idol-making. But this year there is no need, as he does not have much work pressure. “I have been making Durga idols since 1983. This place is 10 years old. I sell around 50 Durga idols, which go to different places including Madhyamgram, Barasat, Salt Lake and Kestopur. This year I don’t even have 50% of the work. I have only received 12 orders so far, that too at a very low rate with only getting Rs 2,000 as advance. I am not even sure that they (puja organisers) will come to receive the idols.”

“We usually start making idols in March but this year I started the work in June. Normally, I get orders for making Durga idols worth Rs 60,000-70,000 for big clubs but this year they have ordered small idols worth Rs 10,000-12,000. All this happens at a time when work is usually at a peak, with many festivals in a row like Annapurna (March), Manasa puja ( mostly organised in homes but good money is spent on idols), Loknath Puja (August), Durga Puja (the biggest one ) and then Kali Puja. And we earn only in this season to survive the rest of the year.

“But this year, we didn’t earn a single penny for three consecutive months. I am not able to feed my children and family and that makes me angry and helpless.

“The government is not thinking about us (referring to the potters community). We haven’t received any help except some kilos of rice through the central government scheme. There is no business.”

The labourers who help potters in building the idols are facing tougher times. Pal, who usually hires labourers to assist him, now has no plans to call them this year

“I can’t call them since I have no work to give them. I used to have around 12-14 labourers but now I only have three because there are no orders. I should be paying each of them at least Rs 500 per day (usually wages vary from Rs 1,000 to 1,500 per day) but I only manage to pay Rs 1,000 per week. And they also have no other option. We all are helpless.”

Sameer Pal runs a small unit making idols for 28 years now and lives in Kumartuli. He usually hired 20-35 small artists or labourers but this year he has given work to only three.

“We started making Annapurna idols in March only like every year but the government announced lockdown and Annapurna puja was canceled amid Coronavirus outbreak in the city. That time all the labourers went back to their respective hometowns. Since then, for three months, everything was shut, we had nothing to do. Now conditions have improved a bit. We have started working. Since Mamata Didi has assured us of Puja this year; we are hopeful that we might earn something. If there is no Durga Puja, it will be a disaster for us. It is Bengalis’ biggest puja—everything is associated with this festival in Bengal. However, we have started working. This year we got orders for small idols. Before that, even small clubs used to order 12-14 feet idols but they are now ordering 7-8 feet.”

In such a scenario, a lot of labourers belonging to Scheduled Castes are facing relatively more hardships. Many among them have been fired.

Vikas Mondol, a resident of Madhyamgram belonging to the SC community has a family of six: wife and four school-going kids. He has been working with Anand Pal for more than eight years as a labourer.

“I make a good amount of money during this festive period to sustain the feast of the year. This is the only work I know. I used to think that an artist will never die of hunger but these days I find it difficult to eat well and each day is a struggle. We had no idea about Covid, and lockdown happened so suddenly, everything just stopped. I can’t do other work to feed my family as there is no source of income for us.”

“I am at least getting something because I live nearby and can come to work. My friends (referring to his fellow colleagues) do not even have this option. I don’t know what I will do if things go on like that. I am worried about the future, about people not spending money on festivals and how we will earn.”

Sukanta Mondal, a resident of Burdwan district of West Bengal works with Sameer Pal as a labourers artist says, “I usually come in March but due to lockdown and since there is no work also, I came in June. For three months, I didn’t earn a single rupee. This lockdown has destroyed people like us. We have slept hungry for nights during lockdown. I never imagined that I would see this day in my life. If not Corona, I would have made some earnings but because of it I couldn’t.

“Here also I am not getting enough money but at least I am able to send something home. No one thinks about us. There is no financial assistance from the government.”

The impact of lockdown was more on labourers, mostly belonging to Scheduled Castes, while artists who are OBCs are relatively safer because they own the business and are relatively better positioned.

Similarly barbers, most of them belonging to the Nai community, were not allowed to open their shops for over three months and still people are avoiding going to them. Still, their profession is getting back on track, especially in small towns where people are visiting barbers’ shops more frequently than metro cities.

Ramesh Sen, a 40-year-old barber who recently re-opened his shop had two helpers — Rinku and Hemant — working in his small establishment but now only Rinku is working with him while Hemant has gone to his village. “I was initially going house to house because I had to pay rent for this shop,” says Ramesh, who doesn’t pay fixed salaries to his helpers. They earn as per the work they do.

Rinku told us that Hemant has started working in his village. He had to spend three months without any earnings. “I was doing nothing in the last two months and the police was not even allowing us to move. Thankfully, our work has started now.”

Raju Mistry, 32, a construction worker from Burdwan district of West Bengal has started working again after four months of halt due to lockdown. He was unemployed for the last four months and was dependent on the government for ration as he is a BPL card holder belonging to SC category.

“I got married last year and came to Kolkata for work. I have been working with senior constructors for more than 10 years. I started working when I was 12 years old with my father. Now I have mastered the art and take my own house contracts. And this is the season of our work from March to Mid-July ( before monsoon). The whole season I sat at home and did nothing. I then decided to go back home in April due to unavailability of work,” he said.

Mistry has returned to work now and is building a 2 room house in the Madhyamgram area, he added, “This is the only project I have right now. I might go back again if I don’t get anything else. Right now these people ( house owners) are providing me a place to stay and two-time food. I never thought that I would have to see this day. I left my hometown because I thought I would earn more here. But this Covid has changed everything.”

In April, we spoke with Sarwan, a harmonium player from the Chamar community. He is still at home waiting for things to normalise. “I made my house by hard-earned money through my music and now five months have passed without work. I have land but my soul resides in music.”

In cities, people are firing their maids due to fear of Covid infections. Students and unmarried professionals are mostly in their hometowns, and those who are staying are not hiring maids, which has caused the unemployment for househelps, maids.

We spoke with Kamla Devi, an OBC who hails from Patna, Bihar and in her late 30s. She works as a maid (mostly cooking) in Delhi. She is married and has a kid. “I have been a cook in houses for more than 3-4 years. I mostly cook in bachelor’s houses as they generally are in need of a cook. When lockdown was announced, initially I did not feel the pinch. But as a month passed, 3-4 of my clients said that they are going back to their hometown, citing work from home. I lost my job. Now I don’t have work.

“I asked my few clients (who only went home for a few months and will come back) for half of my salary. I had no other option than this. I have no job. A few of them agreed and are sending me some amount of my salary even without my working for them. They understand my problem. I am just surviving. Even if this lockdown opens, I think we won’t get a job. Because everyone is scared of Coronavirus. So, many of us (referring to maids in general) lost our jobs because of this reason. Even those who were living in with families were asked to leave. I am hoping that the vaccine will come soon. Otherwise what will we do?”

Caste matters

The national average annual income of the country stands Rs 113,222, according to the paper titled ‘Wealth Inequality, Class and Caste in India, 1961-2012’ which was released in 2018. It says that marginalised castes earn much less than the national average, the average annual income of ST and SC stands at 21 % and 34% respectively, lower than the national average. OBCs and Muslims are relatively better positioned, earning 8% less than the national average.

Among upper castes, forward castes earn 45% more than the national average while Brahmins earn 48% more than the national average.

When caste-based wealth inequality is so well entrenched, the pandemic has been a catastrophic event, leaving the lives of lower caste people devastated.

“Caste is an important social factor, as it is a basis for discrimination in our society. The majority of migrant labourers are from SCs and STs and during the lockdown when they returned, the treatment with labourers belonging to dominant castes was different from treatment with Dalit labourers. So when we study catastrophic events like covid, we can’t ignore factors like caste, class, religion and gender.” explained Economist Ravi S. Srivastava, former Chairman of the Centre for Regional Studies, JNU.

Various states are demanding comprehensive caste-based census. The growing demand for including caste as a category in the 2021 census is because a study of this type last happened in 1931 and given these inequalities, it seems the need of the hour.

Education matters

The Ashoka University paper also says that job losses among lower caste groups was more because of their over-representation in unskilled, precarious jobs. “A prima facie look at worker characteristics suggests that the higher negative impact on SCs might be accounted for, one, by their five times higher representation within the precarious, vulnerable daily wage jobs, and two, by their lower levels of human capital. Consistent with this, we find no caste differences in job loss rates when comparing individuals who do not hold daily wage jobs and have more than 12 years of schooling.”

As per India Human Development Survey for 2011-12 (IHDS-II) 51% of SC adult women and 27% of males have zero education. That shows why the lower caste community was worst hit in terms of employment.

Ajit Ranade, Mumbai based academician,told Hindustan Times, “Researchers find that there is a difference between upper caste and lower caste, especially the Scheduled Castes, in terms of the severity of the negative impact on employment. The upper castes are endowed with higher human capital, i.e. educational achievement, and are in jobs less vulnerable to pandemic disruption. What is surprising is that the impact on SCs is three times worse. Not only has the pandemic exposed the pre-existing inequities but has amplified them. Hence relief and welfare measures have to pay extra attention and compensate for this unequal impact across caste divisions.”

A month ago, a Schedule Caste man Kuldeep Kumar sold his cow — to fund the education of his daughter Anu and son Vansh, who are studying in Class IV and Class II. The news got wide attention and many later came to help him. In this critical time of pandemic, another crucial determining factor is access to the internet, the data tells that access to internet among upper caste households is 20%, while only 10% households of SC community have such access. Education is at a standstill, it will not re-start in the majority of the country until the government allows schools to function. Access to the internet is still very crucial, in terms of access to multiple benefits.

In rural India, especially in tribal villages, that we visited we found that kids in poor families are not involved in any kind of learning. Though private schools in villages are not closed, they don’t have any infrastructure for online education. Those families whose kids are studying in cities are only arranging facilities for their kids for online education and most of them are OBCs, forward castes and Brahmins.

We spoke with the National Executive member from All – India Forum for Right to Education (AIFRTE) Shyam Sonar who stressed upon this issue of access to online education, “As per the NSSO data in Maharashtra, only around 3% rural households have computers and almost 19% have internet access and in urban areas 52% have access — this implies that around 77 lakh families in Maharashtra are deprived of online mode of education in the time of Covid. If you multiply it with just 4, that roughly means over 3 crore families are deprived of access to education. Since the majority of students belong to lower caste groups, whose families have been badly hit by lockdown, are faced with double whammy.”

Sonar also said that since caste based professions like that of Mali, Nai, Chamars castes are hit badly they can’t pay the hefty fees of their kids studying in private schools. “The honorable Maharashtra high court said that the government cannot ask private schools not to charge fees. This is not favouring the poor specially from marginalised communities as they are already facing financial difficulties and now their kids are being deprived of education which is against their fundamental right to education.”

Covid and Caste based violence

Covid pandemic has given the untouchability practices a new life — people have started practising it again — and has also resulted in violence against Dalit communities. In Maharashtra, a 20-year old Dalit youth named Hrishikesh Vhavalkar was beaten up on the false pretext of being Covid postive. And in Haryana, a family was allegedly attacked for not switching off the light at 9 pm on April 5, when PM Modi gave a call to switch off lights and light earthen lamp. Not just that, Covid-linked sexual discrimination and violence was also observed.

“At a time when communities around the world are experiencing severe health and economic issues due to the Covid-19 pandemic, acts of violence on the basis of caste have continued on a massive scale against Dalits and Adivasis in India. While the Covid-19 pandemic affects wider society, in India those, who face existing structural discrimination and social and economic exclusion are particularly vulnerable to its most devastating impacts.” said a report by National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR), an NGO, on impact of Covid on Dalits.

Not just that Covid also caused racial violence against the North-eastern community. Between February 7 and March 25, 22 cases of hate and racial discrimination against people from North East were reported which tells volumes of the discrimination — a Manipuri girl was spated at and verbally abused.

Now slowly, as things are getting back to normal, India’s workforce is returning to their jobs and everyone is hoping to return to pre- Covid time, it is clear that Covid-19 has not impacted all equally– in fact, it has exacerbated existing inequalities. Further studies will tell how much is the impact but as of now the picture is looking very grim.