An anthropologist goes on a trek with a Naxal platoon travelling from Bihar to Jharkhand and returns with an account that portrays rampant casteism among Left-wing extremists in India

In Jharkhand, a London-based professor of anthropology discovered NGO workers in Land Rovers, development funds siphoned off by local elites, votes bought during elections, corporate honchos landing at Ranchi airport to mitigate land acquisition worries, and Naxal armies recruiting tribals in the region. But when her doctoral research supervisor asked her if Naxals were “really a bunch of thugs”, she decided to find out.

This is a brilliant examination of the Naxalite movement, not as an outsider or an academic writing on the subject but as a ‘participant observer’. It familiarises the reader with the world of Naxals, their motivations and conflicts and the sordid path of those who lead the movement forsaking worldly pleasures for the difficult dream of a just and egalitarian society.

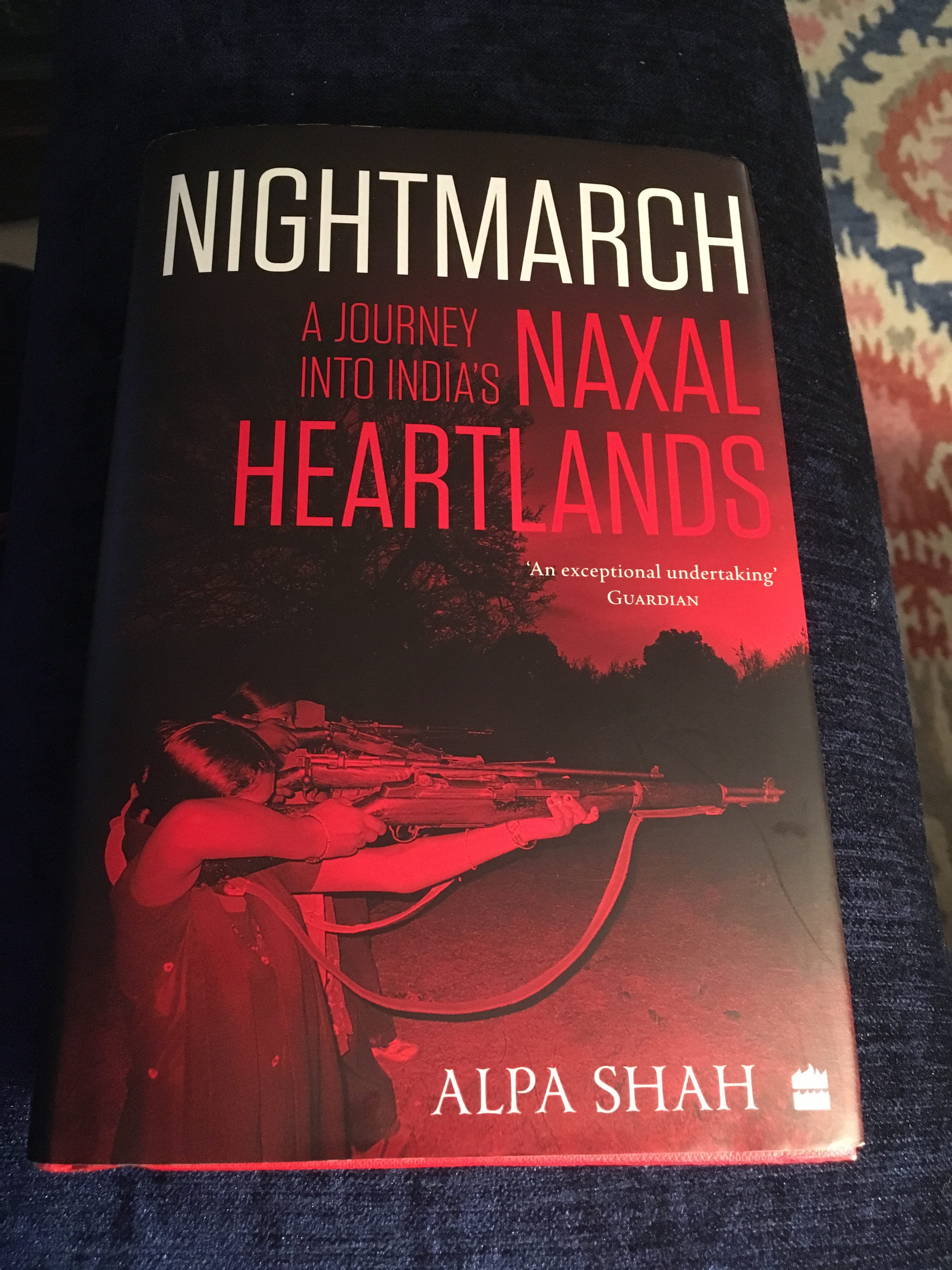

Alpa Shah’s lucid prose sensitively tells stories of conflict, hierarchies, inequality and inherent contradictions in the movement with compelling takeaways for everyone. That’s what takes this book to stand out in political non-fiction. Nightmarch: A Journey into India’s Naxal Heartlands is an insightful exploration of conflict and its origins, and how understanding of both eludes policies for tribals in India.

Shah sought to understand how and why the tribals, mostly belonging to the Scheduled Tribes, often neglected by local administration and governments both at the state and the Centre, were picking up arms to create a ‘different world’.

Between 2008 and 2010, she spent 18 months in the forests of Jharkhand and Bihar living among the tribals in huts without electricity and water. She moved to Jharkhand at a time Operation Green Hunt, a government operation to flush out guerrillas, was launched, making her task more difficult as the tribal communities were far removed socially, geographically and politically from the rest of India and she had to venture into the interiors.

Towards the end of her stay, she joined a platoon of more than two dozen Naxals on their night march from Bihar to Jharkhand on a 250-km trek, dodging scrutiny of police camps and checkposts. This was a dangerous and audacious exercise given that Shah was the lone woman in the platoon, unarmed and new to navigating the rough terrain in the dark of night. But her determination convinced the Naxals and very soon, she was off on a 10-day trek that would allow her to not just connect with the leaders at a personal level, but to also have an intimate view of their motivations, dilemmas and conflicts.

On the night march, Shah meets Gyanji, the seniormost leader, whose soft feet bely his Naxal identity; she later discovers that he comes from an upper caste well-to-do family, committed to bring justice and fairness in the lives of the tribals. With his playful eyes, love for poetry and interest in grooming himself, he is not a typical gun-wielding Naxalite.

Her descriptions humanise Naxal leaders and at times demolish popular myths about the men and women leading the movement. Prashant, with his guns, songs of revolution and books written by Gulzar, Tagore and Russian revolutionaries such as Alexandra Kollontai, is a Naxal driven to the movement after the upper caste feudal army Ranvir Sena burnt his cousins’ house —overnight, he made the transition from being a Naxal sympathiser to an activist. Kohli, with his boyish appeal, joined the movement to escape his father’s reprimand on spilling milk. Clearly, everyone has different reasons to join the movement.

Despite the different backgrounds of its proponents, Naxalism has a common dream of a classless, equal society. In the beginning, it was inspired by Soviet Russia and Maoist China in the 1960s. The seeds of the rebellion resurfaced in later years in the ‘flaming fields’ of states such as Bihar where fierce caste wars between Naxals and dominant caste landlords raged.

Extreme caste hierarchies still plague India society, giving succour to the Maoist movement whose war is against caste oppression and for this, it continues to mobilise the most socially discriminated group, the Adivasis. The most extreme counterinsurgency measures began in 2005, affecting lakhs of Adivasis who were seen by the government as Maoist sympathisers. The crackdown followed the emergence of a new political and military organisation the Communist Party of India (Maoist) and its People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army.

Today, as per government claims, 20 Indian states are Naxal-affected, and Shah describes police action in these states against the guerrillas as the “juggernaut of perhaps one of the greatest people-clearing operations of our times”. The underlying message in the book is that of development pitted against social justice, with corporations invading natural habitats of Adivasis for profit, destroying environment along the way, even as Naxal leaders mobilise the tribals they drive to homelessness.

The author of this book discovered the ‘participant observation’ method as an antidote to armchair research proposed by British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski while she was a university student in London. But the motivation to finally travel to a Naxal-infested, remote Jharkhand village perhaps came from the grit and fortitude of her grandmother who many years had travelled in a small boat to Nairobi in the late 1920s from a dusty Gujarat village. While Shah’s personal history and her father’s secular vales shaped her outlook in life, it was not until her stints in the slums of Delhi for the World Bank that made her want to question injustice and change the world.

Nightmarch is Shah’s account of what she saw when she immersed herself in the lives of Naxals and their ideological war against the Indian state. She is astutely objective in her narrative and reflections, and notes, with profound understanding, how the idealism that holds Naxalism together is very often undone by the movement’s ease with using violence, how a movement modelled on principles of equality can create a more equal society for Adivasi women and how Naxal leaders survive the hardships of jungle life to be betrayed by their own trusted men.

In the end, Shah discusses the contradictions revolutionaries face. Besides being betrayed by their own people as they continue relationship with kins and families, Naxals find themselves ideologically pitted against capitalism when capitalism is needed to fund largescale revolutions. Not just this, their tendency for violent resistance also invites violent state oppression.

Naxal movements have also overlooked the inequalities within their own ranks as men from elite classes have failed to give space for nurturing of lower caste, Adivasi women leaders. Yet, Shah argues that revolutionary movements such as Naxalism have provided an alternate vision of being where individualism, hierarchies and accumulation of wealth via exploitation are discouraged, thereby acting as a democratising force.